“There are two mistakes one can make along the road to truth…not going all the way, and not starting.” –Hindu Prince Siddartha Gautama, the founder of Buddhism

This is it: the end of summer. For my colleagues and me, the new school year formally begins tomorrow, when we gather together the new class of students. A farewell to summer is overwhelmed by the sense of anticipation that a terrific experience is about to begin. We are making a start. Doing this well entails at least two tasks.

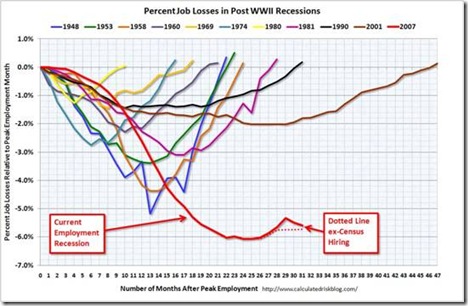

First, a good start acknowledges the context. Certainly, the circumstances of the U.S. economy are bearish. There’s never been a recession without a recovery. But it seems likely to take several years to restore the global economy to the level of activity it enjoyed before the onset of the recent recession. To give you a visual image of the “hole” created by this recession, consider the following graph from the blog, Calculated Risk. It compares the unemployment in the U.S. economy in the most recent downturn versus several previous downturns. The hole is deeper than any recession since the Great Depression. Until employment recovers, consumer spending won’t rise much. Until consumer spending rises, the economy will feel anemic. Until the economy grows robust, we won’t return to the heyday of MBA recruiting: multiple offers, good salaries, and rising promotion prospects.

|

One way to think about this context is as an opportunity. Every trough contains the seeds of the next recovery. A number of famous companies (e.g. Apple, Microsoft, Facebook) were founded in troughs. In the face of the bearish economy, my advice is, don’t look back. Envision the economy to come, not just the one that exists. Live into the vision. It is pretty clear that the conventional wisdom in a variety of industries is being rewritten. In the past year, we have seen new legislation that will dramatically reshape industries as varied as banking, health care, and energy. Develop a view on where these fields are heading. As the hockey star, Wayne Gretzky said, you must “skate to where the puck will be, not to where it is.”

The second task of making a good start is to take responsibility for your own learning. Reaffirm what you are embarking on, and why. The conventional wisdom is that students go to business school to get a job. But that’s not quite right. The point is to get the knowledge and skills, and to build the attributes of character that will help you get a job. The best safeguard you have against a difficult economic environment like this is what’s between your ears!

Some recent reading has shaped my thinking on this second point. I commend to students and teachers alike the book, Why Don’t Students Like School? A Cognitive Scientist Answers Questions About How the Mind Works and What it Means for Your Classroom. It is by Daniel T. Willingham, a colleague in UVA’s Psychology Department. He asks, why does learning “click” with some students, and not others? What drives real learning?

The short answer to the question in the book’s title is summarized on page 1: students don’t like school because “People are naturally curious; but people are not naturally good thinkers; unless cognitive conditions are right, we will avoid thinking. The implication of this principle is that teachers should reconsider how they encourage their students to think in order to maximize the likelihood that students will get the pleasurable rush from successful thought.” OK, cognitive conditions promote good thinking.

At Darden, we take seriously the quest for the “pleasurable rush from successful thought.” Simply yakking at students or demanding rote memorization does nothing to promote the rush. Our approach relies on the much more stimulating approach of high-engagement discussion. We apply a key principle: start from where the student is, not from where the teacher wants to be. One reason we have successful graduates, a highly bonded alum community, and very high rankings for our classroom experience is that we structure our programs in ways to elicit the curiosity, energy, and determination of our students. Telling students the solution to a problem does nothing for their capacity to think. Everything depends on questions—this was the subject of my remarks at Darden’s last graduation: how we teach is what we teach; you can manage by asking questions, and thereby empower your employees to figure things out for themselves. The teacher and manager need to promote puzzlement in constructive ways.

What is the role of the student in promoting good thinking? Graduate school is very different from undergraduate school or high school in that grad students bear much more responsibility for the success of their own learning. How does a student take responsibility for his or her learning? Thinking ((Thinking, according to Willingham, means “solving problems, reasoning, reading something complex, or doing some mental work that requires some effort.” )) is effortful, slow, and unreliable—in no small part because we sail through quite a lot of our day rather automatically, applying past approaches that granted us success. Willingham says, “when we can get away with it, we don’t think. Instead, we rely on memory. Most of the problems we’ve faced are ones we’ve solved before, so we just do what we’ve done in the past.” (p.5) But old capabilities don’t necessarily work in graduate school. In fact, the whole purpose is to develop new capabilities. I’ll offer two suggestions:

· Turn off your autopilot, pay careful attention, and adapt. In previous blog postings, I’ve written about mindfulness (see this, this, and this) and the need to be present (see this, this, and this).

· Find the joy in grappling with the new cases and problems. Willingham wrote, “Solving problems brings pleasure.” (p.8) This is what the Nobel Laureate Richard Feynman called, “the pleasure of finding things out.” Indeed.

Buddha’s words capture well this moment for students, faculty, and staff. We are leaving the summer, the interregnum between job and student life, or the summer internship. The academic cycle starts anew. We are all looking for Truth and seeking to strengthen our capabilities. We wish the context were buoyant, but let’s view it as an opportunity. Graduate students should take a large measure of responsibility for their own learning. Let us make a successful start.