[Here are my remarks for Darden’s 2013 graduation ceremony. I foreshortened my talk a bit to help avoid some approaching rain. What follows is the full message.]

“Never confuse movement with action.” – Ernest Hemingway

Today’s ceremony is an historic event in that we honor the first graduating class of Darden’s Global Executive MBA program. These students traveled far to come to Darden; they traveled far during the program; and they will travel far as new MBA graduates. This prompts the following reflection.

This graduation season, the media will report a range of speeches by famous people, one common theme of which will be to exhort the graduating students to “move out, move away, and move on”—the notion being that they’ve had enough time with the cloistered academic life and that more growth awaits them out in the real world. It’s hard to argue with that—except that “move out, move away, move on” too easily becomes the mantra for professional life in general. Therefore, I choose to take the contrary view this season, and urge you to embark on a professional life where you “hang on, hang in there, and make a difference.” Let me tell you why.

The evidence is growing that professional life in business is not just mobile, it is getting a bit footloose:

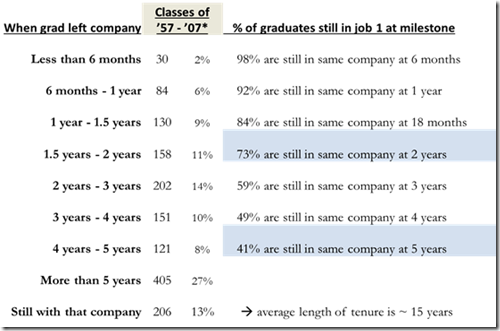

- It is said that today’s MBA graduates are more like entrepreneurs than true employees, and that they are more transactional than relational and therefore more prone to move around frequently. There’s an urban legend that the tenure of the MBA’s job with his or her first employer is short, about 18 months. I haven’t found any rigorous research to support this, but conversations with corporate recruiters seem to affirm this urban legend. You are not much wiser after 18 months than you were after your day of graduation. Nor are you much more valuable to the business community. In one of my blogs, I urged MBA students to think about making a commitment to stay awhile with their first employer—I called it the “five-year hitch.” I’m pleased to say that Darden graduates do stay longer with their first employer: only 17 percent of Darden graduates changed employers within 18 months. ((Here are some results from our All Alumni Survey of 2012, which had over 2200 respondents from across the alumni population. (Note that the Classes of ‘08-’12 are not included as 5 years had not yet passed; this cohort shows 68% still in their first job.)

)) And 41 percent of Darden graduates stay with their first employer for five years or more.

)) And 41 percent of Darden graduates stay with their first employer for five years or more. - The behavior of many other MBA graduates mirrors the broader society. Surveys find that 61% of all employees are open to or are actively searching for a new job. And the median tenure of all job-holders is 4.4 years.

- The median tenure of CEOs of the S&P 500 companies is even shorter: 4 years. In most industries, that’s a fraction of the time it will take to make a beneficial impact. And it’s barely enough time to learn the nuances of a complicated position, such as leader or general manager.

- Then there is the statistic from census data in the U.S. that 13% of all households change address each year. Such mobility is even greater among 25 to 34 year-olds: 21% per year—this means that one out of five of you will move each year. Compared internationally, these rates of movement are high. America is an extraordinarily mobile society. Such movement is costly to communities, businesses, and charitable organizations, not least because your leadership is needed to tackle the problems and seize the opportunities that society faces. This contributes to a decline in social capital described by Robert Putnam in his book, Bowling Alone. Putnam wrote,

“Television, two-career families, suburban sprawl, generational changes in values–these and other changes in American society have meant that fewer and fewer of us find that the League of Women Voters, or the United Way, or the Shriners, or the monthly bridge club, or even a Sunday picnic with friends fits the way we have come to live. Our growing social-capital deficit threatens educational performance, safe neighborhoods, equitable tax collection, democratic responsiveness, everyday honesty, and even our health and happiness.”

All of this movement is not lost on humorists. A journalist friend of mine, Bill Henry, once wrote a farewell column as he was leaving Boston to go to New York to take up a job with a big magazine. He said something to the effect of “When you’re young and in your twenties, you should live in Boston and pretend you’re still a student. When you’re in your thirties, you should live in New York and prove that you can make it in the big time. When you’re in your forties, you should move to Washington D.C. and pay your dues to society. And when you’re in your fifties, you should move to Los Angeles and pretend you’re a student all over again.”

Consider the alternative. George David, Darden MBA Class of 1967, worked for United Technologies Corporation for 23 years. He served as UTC’s CEO for 14 years. The year he retired, he came to Darden and spoke to our community. His message was that commitment to an enterprise and continuity of leadership are hugely valuable—they produce high levels of domain knowledge, which becomes the foundation for high performance. If domain knowledge matters, then keeping planted in one sphere is very important.

In contrast, George David’s chief competitor was Jack Welch, CEO of General Electric. Welch believed in the theory of the “best available athlete” as the criterion to fill any managerial position. For instance, in picking someone to run GE’s locomotive business, Welch might pick one who had been running operations in the light bulbs or medical equipment. His presumption was that if you’ve seen one operation, you’ve seen ‘em all.

George David had a different view. He believed in appointing managers who knew the business best. For him, that meant recruiting managerial talent carefully and then growing it over long periods in whatever business the candidates might be, such as helicopters, air conditioners, or elevators. The interesting thing is that Jack Welch’s successor, Jeffrey Immelt, has since disavowed the “best available athlete” theory.

Among Darden’s alums, I see some great examples of what it means to “Hang on, hang in, and make a difference.”

- Paul Hamaguchi (Darden MBA 1970) lives in Tokyo, Japan, and is CEO of Higetu Shoyu Company, Ltd., a 400-year old producer of soy sauce. Paul has worked with that company since 1979.

- Gordon Crawford (Darden MBA 1971) lives in Los Angeles where he has worked as a securities analyst and portfolio manager for Capital Research and Management for 40 years. Gordy rose to be a top expert in media and entertainment. He served as Chairman of Southern California Public Radio and Vice-Chairman of the Nature Conservancy.

- Lem Lewis MBA 1971, was the first African American to graduate from Darden. He rose to EVP and CFO Landmark Communications in Norfolk and worked for nearly three decades with the company. Today he serves the community with his leadership. He’s on various charitable boards, including the Darden School Foundation. And he chaired the board of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

- Elizabeth Lynch, MBA 1984, worked for Morgan Stanley for 22 years, eventually retiring as Global Chief Operating Officer of their Equities Research business. She has been a wonderful supporter of Darden and told the students in General Managers Taking Action, “Do new MBAs get it? I want to see commitment to culture, loyalty, and learning. Always be wary of the person who’s had three jobs in five years.”

My point is that these people had huge impact in their work and lives through long-term dedication to one organization. They hung on, hung in, and had an impact. Their ability to gain senior leadership probably had something to do with hanging on. About two-thirds of all CEOs of the S&P 500 companies were internal appointments; and on average, they spent 12.8 years with their company before being appointed.

So continuity matters; domain knowledge matters; and persistence matters. You can’t have much impact on the world around you if you are constantly on the move. Therefore, my advice is not “move out, move away, move on.” Rather it is “hang on, hang in, and make a difference.” Dive in to the challenges faced in your community. Make an in-depth study of your industry and your company’s products and services. Volunteer to help with anything. And invest deeply in building relationships within your firm—and not just with your bosses or peers; but start with the humblest employee in your space—this could be the person who delivers packages, or picks up trash, or serves your coffee.

I want to be clear that it may make a great deal of sense to “move out, move away, and move on” if you distrust the leadership of an organization, or if its ethics and treatment of people don’t meet your standard, or if you simply feel called into a different line of work. But even then, it may make sense to stand and fight for what you think is right. The distinguished economist, Albert O. Hirschman argued that “exit” is not always the desirable or rational response to a disagreement with an organization. What matters is the “voice” you can find and your depth of loyalty to the mission and values of the organization.

It may seem ironic that I’m standing here today to help you “move out, move away, and move on” and yet I’m giving you this message to “hang on, hang in, and make a difference.” Please understand, I’m not suggesting that you stay at Darden beyond today; but I am urging you to find your calling and do so with loyalty to your values and vision for society—and this will entail persevering to build the organizations on which society depends. That’s how you will have an impact with your career and how you will find fulfillment.

Please accept my best wishes to you all on your ability to “hang on, hang in, and make a difference.”