“Laissez-faire is dead…The all-powerful market that always knows best is dead.” (September 2008, Nicholas Sarkozy)

This is not a recovery, this is an “emotional, social, and economic reset.” (November 6, 2008, Jeffrey Immelt)

“…a nagging fear that America’s decline is inevitable…the next generation must lower its sights.” (January 20, 2009, Barack Obama,)

“The bubble has burst…this is a once-in-a-lifetime economic event…a fundamental economic reset.” (February 2009, Steven Ballmer)

“the new normal” and “potent cocktail – a self-reinforcing mix of De-leveraging, De-globalization, and Re-regulation… that disrupt the normal functioning of markets and the global economy.” (May 2009, Mohamed El-Erian)

On their face, recent events would seem to confirm what these eminent seers declared back in 2008 and 2009: capitalism, particularly in the developed economies, has descended into a “new normal” considerably less appealing that the buoyancy of the 50 years following World War II. Some straws in the wind:

· The 2010 book, The Great Reset, by Richard Florida is a prominent expression of the view that we are in a “new normal.” In essence, he argues that the Global Financial Crisis has triggered a reaction to the pervious era of unbridled consumerism, aggressive use of debt financing, winner-take-all corporate management, and so on. Though Florida does not court embarrassment by making an economic forecast on which an investor could act, he does argue that this reaction will be a long period of austerity not unlike the Great Depression (1931-1940) or the Long Depression (1873-1896) in American History.

· Prominent economists such as Robert Gordon, Tyler Cowen, Carmen Reinhart, and Kenneth Rogoff suggest that America may be in for a long slog of slow growth—I summarized their messages in a recent blog post.

· John Boehner, Speaker of the House, gave a speech last week in which he mourned the “new normal” economy that America faces and advocated every business and person to create wealth.

· At the other end of the political spectrum, Senator Bernie Sanders decried the “new normal” and wrote in the Guardian that “We must not be content with an economic reality in which the middle class of this country continues to disappear, poverty is near an all-time high and the gap between the very rich and everyone else grows wider and wider.”

· Trustees of pension plans and charitable endowments foresee mid-single digit returns on a diversified portfolio of investments in the future. This prompts them to propose cutting the typical investment draw rate, 4.5%, to something much lower, saying “get used to it; it’s a new normal.”

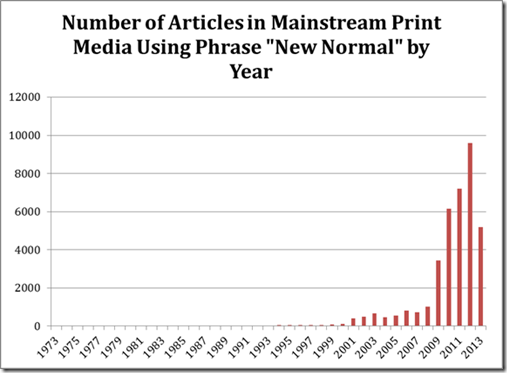

· The following graph shows the mentions of “new normal” in periodicals in recent years. Plainly, “new normal” is a meme, an idea that appeared with the collapse of the Internet bubble in 2001 and really surged in 2009. By now, it is an idea firmly rooted in the public consciousness.

Readers of this blog have seen my agreement that our recovery from the Great Recession will be slow. We are likely to return to higher employment that we experienced before the Global Financial Crisis only in the latter part of this decade. Certainly, our slow recovery to date is consistent with Richard Florida’s forecast in 2009.

I don’t have a crystal ball; and anyone who claims to have a crystal ball is lying. I do worry a bit when there is so much unanimity in a diverse population. Perhaps the unanimity is proof of “new era” thinking and a signal that conditions are about to change.

In a recent post, I highlighted “new era” thinking as a very important foundation of a market bubble—we can generalize “new era” thinking to be an attribute of major economic turning points, in the opposite direction. Research documents the tendency of markets to “overshoot” or overreact to changes in the economic fundamentals. For instance, retail investors tend to sell out well after the “smart money” and after prices have subsided to a level consistent with rational valuation; this added selling causes markets to “undershoot,” driving prices below levels consistent with a realistic outlook. There is a similar tendency for retail investors to buy in during the late stages of an economic expansion.

I wonder whether the ubiquity and persistence of the “new normal” meme signal a “market top” for this idea. In recent years, Jeremy Grantham, a iconic investment manager, has been almost Cassandra-like in warning about the perils of the “new normal.” But in his most recent investment letter, he acknowledges “two trends that might just save our bacon.” His dour letter won’t prompt dancing in the streets, but it certainly suggests a sea-change.

What are business leaders and investors to do with the concept of the “new normal”? Here are some suggestions:

First, challenge anyone who uses the phrase (your chief of forecasting, perhaps) to define it in any rigorous way. I’ve tried this with a cross-section of business practitioners and gotten some pretty mushy replies. Here’s the best I can say: a “reset” embodies the consciousness that this time it really is “different.” The “new normal” as triggered by a “reset” is a downward step-change in welfare, outlook, and self-confidence. A “reset” is transformational: big, costly, enduring, pervasive, and unanticipated.

The power of “new normal” and “reset” may be their usefulness to leaders in mobilizing constituencies at both ends of the political spectrum. The Left has harnessed this meme to motivate a stimulus funding program, health care reform, and re-regulation of the financial services sector. On the Right, the meme underpins a spirit of regime change displayed by Tea Party and Libertarian candidates who argue that most of what the government does is unaffordable now and in the years ahead. Thus, the meme has influence in the way that Humpty-Dumpty told Alice in Through the Looking-Glass:

‘When I use a word,’ Humpty Dumpty said, in a rather scornful tone,’ it means just what I choose it to mean, neither more nor less.’

‘The question is,’ said Alice, ‘whether you can make words mean so many different things.’

‘The question is,’ said Humpty Dumpty, ‘which is to be master – that’s all.’

Next, it is worth asking, “Is this it? Are we in a “reset”?” Without a rigorous definition, how can we tell? The proponents argue that we are in a reset because it started with a bank panic, like other resets. It is global in scope. There is clear job destruction. The recovery is slow and is accompanied with a big transformation in various industries, such as housing and finance.

But on the other side are some possible objections. We have seen many bank panics and relatively few “resets.” The appearance of a panic in 2008 is not a perfect predictor of the next reset. Though the Global Financial Crisis rippled around the world, some regions (China, India, Brazil) remained buoyant for a considerable time. Though housing and finance were badly damaged in the crisis, sectors of the economy such as energy and health care showed relatively little harm. Though unemployment is worse than in many previous recessions, it remains a matter of considerable debate as to whether the unemployment is structural in nature, or purely cyclical. Deleveraging always occurs after a financial crisis. Anyway, when hasn’t the U.S. economy been in some stage of transformation?

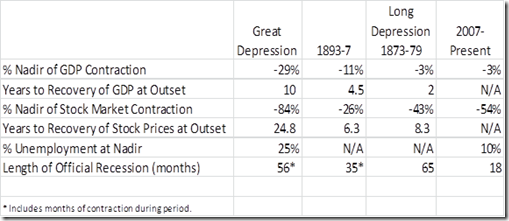

Third, one should ask, “Is this “reset” like other resets?” The following table offers a profile that so far does not look much like the Great Depression, Long Depression, or the depression of the 1890s. The recent crisis and recession stand out for the very slow recovery, but not for the depth of the damage.

It’s a stretch to imply that the present “new normal” compares to earlier depressions. The current situation lacks the pervasiveness of antecedents. Nevada and the city of Detroit are devastated; Utah and Washington D.C. are not. Greece, Iceland, and Ireland are plainly in deep distress, but China and India have been relatively buoyant. Industries such as housing, financial services, and print media were hurting, but oil & gas, health care, agribusiness, and information technology barely broke stride.

The present social and political environment doesn’t compare well to historical examples. We have had rallies in Washington, Occupy Wall Street, and Tea Party populism, but have yet to see a populist presidential hopeful on the order of William Jennings Bryan (1896), the demagoguery of Huey Long and Father Coughlin (1930s), Coxey’s Army (1894), the Bonus Army (1932), the violence of the steel and Pullman strikes (1894) or the Molly Maguires (1875), and long bread lines of the Great Depression. Such kinds of events may yet appear in this cycle, but until they do, how can one be certain that we are now in “reset”? Pundits hopefully suggest that a political regime change is imminent in 2014 or 2016, though such is not unusual for the second term of a Presidential administration.

To be sure, the present high unemployment, low growth, fragility of the recovery, and fiscal deficits of the U.S. are serious, unsustainable, and unacceptable. They could unravel into another correction and serious social unrest if not reversed soon. In this sense, perhaps the events of 2007-2010 could better be labeled a “preset,” a precursor to a much bigger realignment that awaits the U.S. economy if fundamental problems remain unaddressed.

Fourth, one should ask, “If we are in a “new normal” triggered by a “reset,” when did it start? Most pundits reply that the “new normal” was triggered by the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-2009. But there are very plausible alternatives:

o 2001? Internet bubble pops, Enron, 9/11.

o 1989? Collapse of Soviet sphere; “end of history.”

o 1973? First oil shock.

o 1971? Abandonment of Bretton Woods system.

Economic historians some years from now will earn their pay trying to parse the actual onset of the “new normal” from the alternatives. Suffice it to say, if we can’t pinpoint the beginning, how can we be so sure of the ending, or even the very existence of the “new normal”?

Finally, one should fight acceptance of the “new normal.” Some folks I’ve met express a weariness with the slowness of the recovery: “New normal? So be it.” But this is defeatism. It is in no one’s interest for America to sustain the “new normal” for very long. James Pethokoukis argued this in a blog :

So what to do? One option is acceptance. Accept that we will never fully close the growth gap or income gap or jobs gap. Accept that unemployment will never return to the levels of the Bush and Clinton years. It’s time to move on and be grateful that America avoided an outright depression and isn’t suffering recessionary relapse as Europe is. The Dow and S&P 500 are making records, and home prices are again rising. Slow and steady is better than bubbles and busts, right? Forward!

The other option is defiance. Refuse to embrace the “new normal” reality. Refuse to lower expectations of what America can be. As Larry Kudlow likes to say, “Growth, growth, growth!”

Next November 14 and 15, Darden will host the sixth annual University of Virginia Investing Conference. The theme of the conference is “Finding Opportunity in an Unpredictable World”—this confronts the mentality of the “new normal.” Where can asset managers find attractive returns?

Industry experts from around the world, hosted by Darden’s faculty, will probe innovations and investment ideas that could help the decision-maker respond proactively to current conditions.

Speakers include:

- Kyle Bass, Managing Partner, Hayman Capital Management LP

- Joyce Chang, Global Head of Fixed Income Research, JP Morgan Securities LLC

- Tony Crescenzi, Executive Vice President, Market Strategist and Portfolio Manager, PIMCO

- Henry Ellenbogen, Portfolio Manager, T. Rowe Price

- Alice Handy, Founder and President, Investure

- Ned Hooper, Partner, Centerview Capital

- Joseph “Jody” A. LaNasa III, Managing Partner, Serengeti Asset Management

- Scott Malpass, Vice President and Chief Investment Officer, University of Notre Dame

- Howard Marks, Chairman, Oaktree

- Jason DeSena Trennert, Managing Partner, Chairman & CEO, Strategas Research Partners LLC

- Wil VanLoh, President & CEO, Quantum Energy Partners

- More speakers will be announced soon.

Registrations for the conference may now be made. Reserve your seat today and gain some insights to deal with the “new normal.”