The Guardian, June 10, 2012.

Power always reveals—that is the premise for a year-long seminar that I’m guiding to draw leadership lessons from the autobiographies, biographies, and principal speeches of the post-Watergate Presidents (i.e. those from 1974 to the present). These Presidents are closest to the reality of today’s MBA students and rose to the position through an incredible selection gauntlet. Their styles and actions are minutely documented, making it possible for us to see them in detail. If Robert Caro is right, the clarity about these seven Presidents should help us to understand the use of power and execution of leadership. What leadership insights might their use of power reveal? Most generally, what meaning might we make of the story of any leader?

Our seminar convened on September 1 to discuss the biography and memoir of Gerald Ford, ((Time to Heal, by Gerald Ford and Gerald Ford, by Douglas Brinkley)) who served as the 38th President, from August, 1974 to January, 1977. That was an inauspicious moment in history at which to start a study of leadership.

Ford’s Presidency: Brief Highlights

Ford’s administration began at the nadir of popular support of the presidency, a moment of a profound crisis of trust. President Nixon resigned in disgrace in August, 1974, having been accused of obstruction of justice in investigations about the break-in at the Democratic National Headquarters in the Watergate in 1972. Earlier, Vice President Spiro Agnew had resigned following a charge of corruption. Ford was part of a difficult leadership episode in American history. During the two decades of leaders from 1960 to 1980, no one served two full terms, owing to loss of reelection (Ford and Carter), drop out of re-election (Johnson), resignation (Nixon), or assassination (Kennedy). Ford was the only President in U.S. history not to enter the White House by means of a national election as President or Vice President. One poll found that over 80% of the people believed that Ford did not have the ability to run the country. He was mocked as the “accidental President.”

Nor was the rest of his incumbency easy. Ford dealt with the withdrawal from Vietnam, the economic aftershock of the OPEC oil embargo, Congressional investigations on domestic intelligence abuses, rising inflation, the Mayaguez incident, budget deficits, the Swine Flu scare, Middle East tensions, relations with China, the Turkish invasion of Cyprus, and the Indonesian invasion of East Timor. Ford himself survived two assassination attempts.

Ford has been described variously as “a decent man,” a team-player, ego-less, steady, dependable and a centrist. As a star athlete at University of Michigan, he learned the virtues of self-discipline, practice, and sacrifice for the team. His lifetime of service in the U.S. House of Representatives developed his skills of coalition-building and negotiation with political opponents. As Republican Whip and the House Minority Leader, he grew to value cohesion and loyalty to the party. Ford described himself as an economic conservative, social moderate, and internationalist. Military service in World War II led him to believe that security of the nation depended on active engagement and leadership in the global community—this was a marked turnaround from isolationist views he held before the war.

Upon rising to the Oval Office, Ford immediately sought to set a tone of “healing” to address the crisis of trust (the title of his memoir conveys this dominant tone, A Time to Heal). “Our long national nightmare is over,” he declared in his inaugural speech. He pledged candor and openness, sought to create national unity in the face of partisanship, initiated a program by which Vietnam War draft resisters could achieve a presidential pardon, and pardoned Richard Nixon for the obstruction of justice. He sustained Nixon’s international policies and retained Nixon’s presidential staff and Cabinet, notably Henry Kissinger. For his pardons and retention of Nixon’s staff, he was vilified in the press and by both the left and right of the political spectrum. To respond to mounting inflation, he announced a program to “Whip Inflation Now” (WIN), a program of voluntary belt-tightening aimed at reducing demand and married with tax increases on corporations and wealthy individuals. All this occurred within Ford’s first three months in office. The unpopularity of these actions prompted a resounding defeat for Republicans in the mid-term elections of November 1974. The Democrat-controlled House and Senate that returned to Washington in January 1975 challenged Ford for the rest of his incumbency.

Ford’s style as an administrative leader marked a break from Nixon. Where Nixon relied on a strong Chief of Staff as a gatekeeper, Ford wanted to be more accessible at the center of a hub-and-spoke administrative system with little staff filtering. Later, recognizing the overwhelming volume of issues and interests that came to the White House, Ford eventually acceded to stronger staff intervention. But throughout his career, Ford proved to be a “big picture” leader, who relied on others to master details—this non-mastery proved to be a critical part of his defense of his pardon of Nixon (i.e., that Ford had no prior knowledge of Nixon’s obstruction of justice) or of CIA improprieties.

Ford’s execution of his own policies drew more criticism. He recruited Nelson Rockefeller as his Vice President and later dropped him when running for re-election. Ford appeared to “flip-flop” on budget-cutting: at first, his WIN program sought to cut expenses and balance the budget; soon he abandoned that policy in the face of a recession and overwhelming Congressional pressure and signed a deficit-expanding budget. He was unable credibly to shake allegations that he had accepted some kind of deal to pardon Nixon. He went to Helsinki to negotiate a ground-breaking agreement with the Soviets on human rights, only to face a barrage of criticism upon his return home. He proved to be a lackluster communicator on TV and stumbled in debate with Jimmy Carter.

Ford’s was the second-shortest incumbency in the 20th Century and the fifth-shortest in U.S. history. Short tenure in office is bound to affect one’s impact and legacy. With the exception of Kennedy and possible exception of Ford, the ten shortest-tenured Presidents left rather empty legacies.

|

U.S. Presidents, Shortest Days in Office and Rank in Poll of Historians |

|||

|

Days |

Rank |

||

|

William Henry Harrison |

32 |

39 |

|

|

James A. Garfield |

200 |

31 |

|

|

Zachary Taylor |

493 |

35 |

|

|

Warren G. Harding |

882 |

42 |

|

|

Gerald Ford |

896 |

26 |

|

|

Millard Fillmore |

970 |

38 |

|

|

John F. Kennedy |

1038 |

11 |

|

|

Chester A. Arthur |

1263 |

28 |

|

|

Andrew Johnson |

1420 |

40 |

|

|

John Tyler |

1431 |

37 |

|

A recent ranking of Presidents by historians puts Ford in the second quartile from the bottom. Historians tread carefully in discussing Ford’s presidency but their sentiments echo the rankings (“unique” “obstructed,” “stalled,” “mediocre,” “tarnished,” “cautious.”)

With the passage of time, critics relented and even reversed their judgment of Gerald Ford. The John F. Kennedy Foundation gave Ford its 2001 “Profile in Courage Award” for pardoning Richard Nixon. Ted Kennedy, one of Ford’s leading adversaries in the 1970s, said, “I was one of those who spoke out against his action then. But time has a way of clarifying past events, and now we see that President Ford was right.”

In sizing up a President, what questions should we ask?

Our seminar discussion chewed over the details of Ford’s presidency. Five “buckets” of concerns seemed to matter in our assessment:

· Circumstances. Stuff happens to any leader: crises, changes in the economy and political environment, the prevalence of urgent issues to deal with, and the strength (or weakness) of the mandate with which one assumes leadership. Ford parachuted into a maelstrom. The first step in assessing a presidency is to appraise the special circumstances that the President faces.

· Character. What a leader brings to the office matters. As Aristotle said, “Character is destiny.” “Character” serves as an umbrella for a range of personal attributes such as values, priorities, life experience, ideology, personality and purpose. In his classic book, Leadership, James MacGregor Burns wrote that:

“Essential in a concept of power is the role of purpose….[Transformational leadership] occurs when one or more persons engage with others in such a way that leaders and followers raise one another to higher levels of motivation and morality…Their purposes, which might have started out as separate but related, as in the case of transactional leadership, become fused. Power bases are linked not as counterweights but as mutual support for common purpose. Various names are used for such leadership, some of them derisory: elevating, mobilizing, inspiring, exalting, uplifting, preaching, exhorting, evangelizing. The relationship can be moralistic, of course. But transforming leadership ultimately becomes moral in that it raises the level of human conduct and ethical aspiration of both leader and led, and thus it has a transforming effect on both.” (pages 13 and 20).

Character (purpose) plays a vital role in leadership. In the assessment of historians over time, Ford’s character (his decency, steadfastness, and moderation) is the defining attribute of his legacy as a leader: “healer” President. A second step in assessing a presidency is to inquire how a President’s character stands out, while in office and changes over time.

· Choices. The President cannot escape from making hard decisions. Those choices are the tangible footprints of leadership. Our seminar paid particular attention to the tone that Ford sought to set for the nation, the prioritization of issues and agenda, the organization of the White House staff, and preparation of the budget. A third avenue of inquiry is to discern which choices proved to be pivotal in the President’s incumbency.

· Execution. Implementation of the President’s program is another weighty indicator of leadership: how is it done, and how well? For instance, in his book, Soft Power, Joseph Nye has distinguished between using “hard power” (coercion through threats, force, and money) and “soft power” (persuasion, attraction, and appeal). The President must choose the kind of power to wield, and how to use it. Skills of communication and negotiation are crucial. The recruitment of talented and effective staff and of allies and coalition partners is indispensable as well. The President cannot only take; he or she must also give: judging where and when to compromise is vital. Fourth, how well did the President implement the agenda?

· Outcomes. Our seminar gave considerable attention to what we might mean by “success” and “failure” in the presidency. Some defined success as the ability to achieve the policy agenda, to win elections and Congressional passage of legislation, and to create a legacy of high esteem. At several points in our discussion, students noted the tension between “legacy” and other measures of presidential success—maybe by doing the right thing (pardoning draft resisters and Nixon) one loses elections. Any discussion of a presidency invites two final questions: did the President succeed? And by what standards do we measure success?

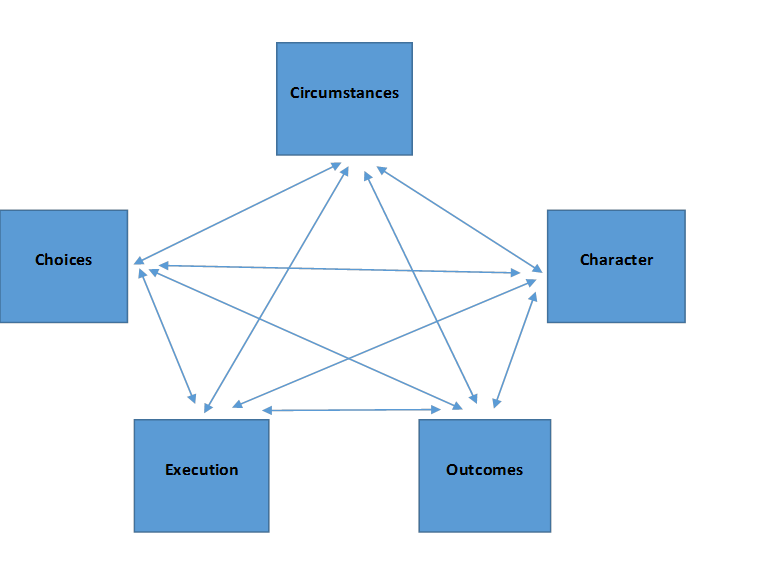

The elements of Presidential leadership seem interdependent.

The presidency of Gerald Ford suggests that circumstances, character, choices, and execution are related to outcomes, but in a non-obvious way. It is too simplistic to say that if you have one kind of input, you’ll get a certain kind of result as President. When one takes into account the evolution of a presidential administration over time, these five buckets seem interdependent. Circumstances, character, choices, and execution affect outcomes as well as each other. We should not look at a President’s leadership as static. The interdependence of the buckets becomes vivid as the President’s leadership plays out over time.

As circumstances change, the President must adapt character, choices, and execution–or fail. World War II prompted Ford’s conversion from isolationism to internationalism. For much of his career, Ford was a Cold War hawk—yet he also sought a nuclear disarmament treaty with the Soviets and presided over the withdrawal from Vietnam without victory. Ford was a consummate legislative leader who was unable to translate that skill into a successful legislative program once he occupied the Oval Office.

Of course, the interdependence can work in other directions as well. Ford gambled that his choices about healing, openness, and pardons for the accused would temper the popular distrust of the presidency—yet for the balance of his incumbency, it inflamed the distrust. Execution can affect choices: Ford’s maladroit TV addresses and debates diminished his popular support and narrowed his range of political flexibility.

Interdependence and feedback suggest a richer way to think about presidential power and leadership. Actions or positions taken in any of the five elements in the system feed back to other parts of the system. The following figure gives the general idea: each arrow indicates one path of the feedback. Obviously, this can get complicated. But the chief implication is that simple explanations about the success or failure of a President are probably incomplete, incoherent, and/or wrong.

Conclusion

Our exploration of leadership in the presidency of Gerald Ford offers many possible insights. Several of them warrant more discussion over the year ahead:

1. Five buckets. We seemed to collect our thinking around circumstances, character, choices, execution, and outcomes. Do these buckets suffice? Are there more?

2. A presidency is dynamic, not static. An assessment of the president at one moment in time may be overshadowed by the next moment, as the volatility of polling results shows. How shall we take into account dynamism and mutability as we assess the President’s use of power and implementation of leadership?

3. Feedback matters. Let’s reflect on how one dimension of presidential leadership affects the other dimensions as time progresses. Maybe good leadership is about managing well the interactions among the buckets. As we consider the record of a leader, where and how does feedback among leadership elements prove consequential?

4. If feedback matters, then performance of a leader is contingent, because the impact of feedback is uncertain. For instance, we can’t just say that “if the President has a strong majority in Congress, a strong character, or excellent communication skills, then success will happen.” At best, you can say, “it depends.” Therefore, perhaps we should try to step into the President’s shoes and re-create the odds of success that underlay the President’s choices.

5. Learning matters. If a leader is inundated with feedback among these components, then paying attention and adapting well is important. The foundation for doing this is a learning mindset. (For more on this, see Carol Dweck’s book, Mindset: The New Psychology of Success.) Of course, the President could be motivated to be bold and self-confident, to take charge, and give orders, all of which militate against listening well, reflecting, and tolerating dissent. Therefore, perhaps we should consider how well the Presidents listen and learn.

“Power always reveals,” said Robert Caro. I think he got that right. Our reading of Gerald Ford reveals a host of insights about power and leadership. There are more to come as we turn to Jimmy Carter and his successors.