This continues a running commentary that parallels a new course that I’ve started at Darden, “Financial Innovation: Opportunities and Problems.” On August 29-30, we explored several important themes in articles by James Van Horne, Josh Lerner, Antoin Murphy, Robert Shiller, and Scott Frame and Lawrence White. We studied the case history of John Law’s meteoric rise and fall in 1720 with the bursting of the Mississippi Bubble. And on August 30th, we heard a presentation from Pascal Bouvier, a fintech venture capitalist. What are we to make of all of this?

1. “Revolutions” in financial innovation do occur, and should be assessed with caution. At the close of class the previous week, we debated the extent to which the blockchain “revolution” was substance or hype. James Van Horne took us back to 1985, when he described a recent wave of financial innovation and warned that it can lead to “excesses.” The problem with frothy episodes of financial innovation is that they can advance meaningless and ephemeral new products and services, inflate bubbles in asset valuations, and promote outright frauds. There are many cautionary examples in history; the story of John Law is an iconic example. A financial genius, Law is credited with strengthening the concept of a central bank, organizing one of the earliest international trading conglomerates, commercializing the concept of financial options, organizing an options market, and arguing that shares in an enterprise were effectively another form of “money”—in the early 18th Century, any one of these would have been a big deal; altogether, they were “yuuuuge.” And Law was a master practitioner of co-opting the state: with patronage from the King of France, he amassed monopolies on foreign trading rights in return for which he proposed to restructure the national debt of France. Law’s problem was that some worthy ideas gave way to excess.

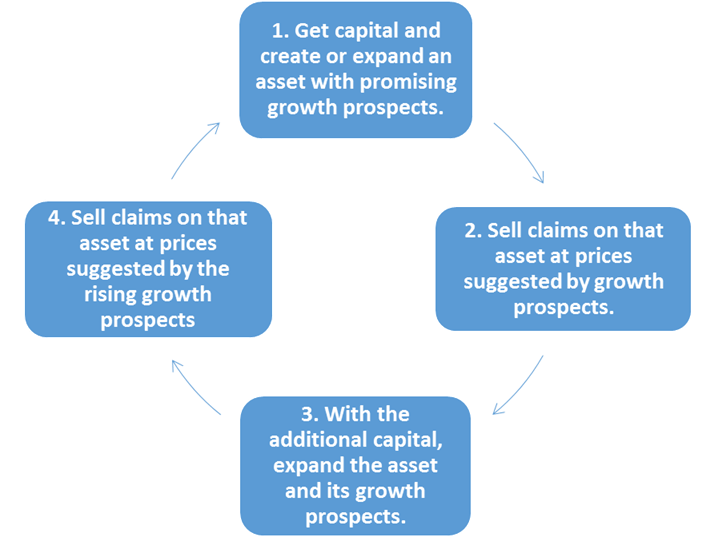

2. Momentum strategies always end in tears. In order for Law to succeed with is audacious plan, he needed to raise more capital, and at higher share prices. To justify higher share prices, Law extolled the promising growth of trade with the Mississippi Valley and other regions. The buoyant expectations soon turned to speculation and then a massive bubble. In the summer of 1720, investors awoke to the realization that real growth of trade with the Mississippi Valley or even real growth of the entire French economy would never warrant the lofty share values. Thus, the bubble collapsed; John Law fled the country; and financial innovation in France was suppressed for decades. Nevertheless, the model of momentum growth is a hardy weed in the business garden. Examples such as Enron, Boston Chicken, and the dot-com bubble of 1998-2000 speak to its durability. The following figure illustrates the “self-reinforcing cycle,” as systems analysts call it: each new infusion of capital fuels more growth, which justifies higher prices for the next infusion of capital. But momentum growth strategies always fail because of declining returns to scale: eventually firms run out of enough promising assets necessary to justify the high growth expectations. Stated alternatively, the Mississippi Company couldn’t grow indefinitely faster than France and its colonies without eventually owning it all! The lesson for budding practitioners in law, business, and public policy: learn to recognize a momentum strategy and call it out.

3. Who innovates? John Law illustrates one other point: Financial innovation seems likely to come from the periphery, rather than the center, of a field; from entrants rather than incumbents. The articles by Josh Lerner and by Frame and White helped to illustrate this. In a world of only big firms and oligopolistic competition, it seemed that only big firms (incumbents) would have the capital and incentive to innovate—this was the thesis of Joseph Schumpeter, one of the great economists of the mid-20th Century. Iconic examples such as Bell Labs (of AT&T) and Xerox PARC (of Xerox) seemed to prove Schumpeter’s thesis. But thanks perhaps to deregulation and technological change, the pattern in the financial sector seems to be that players on the periphery innovate and that big, established incumbents imitate, quickly. To be clear, “the periphery” means different things to different researchers. Josh Lerner describes it as “small firms,” “less profitable firms,” “older, less leveraged firms located in regions with more financial innovations.” Frame and White tell us that “the early issuers were those that tended to be higher risk and also tended to be banks and thrifts (which had relatively liquid assets that could be placed in over-collateralized special funding vehicles).” The research suggests that the prominent incumbents in the financial sector are likely to be followers and adopters of innovations, whereas players closer to the periphery are likely to be the innovators. John Law is an extreme example of the outsider-innovator: a Scotsman who fled to France from England, an alleged murderer, and a “gambling dandy” and bookmaker entrusted with the national fisc. In obvious ways, Law is not a life example for students to follow. So we looked at Bond Street, an online lender to small and medium-sized businesses, and asked why big banks aren’t imitating that model? Students pointed to the tendency of big banks to emphasize economies of scale: make only big loans to big firms and watch those clients closely. In short, John Law, Bond Street and academic research suggest that if you want to look for the source of innovation in finance, you should look toward the periphery.

4. Fintech is booming. Perhaps the biggest illustration of innovation-from-the-periphery is the growing mass of fintech startups, some 18,000 of them in the world, according to Pascal Bouvier, a venture capitalist, CFA, Darden MBA (1992), and blogger in fintech. We hosted Bouvier for a class session. He quoted Marc Andreesen that “software is eating the world” and explained that “code is replacing what is done manually.” Change in financial services has come slowly because of heavy regulation. But the financial crisis of 2008 has opened the door to financial innovation. Over the next 15 years this industry will reinvent itself, he says. Because of innovations, he anticipates a big decline in employment in the financial services sector. He noted that the charge on intermediating assets has been stable at 2% for more than a century and that the wave of innovation will drive this charge downward. Incumbents seem to have a hard time innovating because of their corporate cultures that focus on “risk management” rather than “risk-taking.” Venture capitalists invested several billions of dollars in fintech startups in 2015—Bouvier mentioned the payment systems segment as especially attractive. It certainly seems as if the fintech field has momentum, but that may also be its problem (see point #2).

In the next few classes we turn from “who innovates” to “what motivates financial innovation”? The discussions this week suggest that entrants/outsiders/players-on-the-periphery are better at seeing opportunities to innovate. But what is it that they see?