In this guest post, Jonathan O’Connor, a rising second-year student in the full-time MBA program at Darden, shares his insights about using business principles to help solve social problems. In particular, he shares his story of co-founding LifeNet International, a nonprofit that improves performance of primary care clinics and hospitals in Burundi, East Africa.

In 2008 I had been working as an investment analyst with CNL Real Estate Advisors when a mentor approached me with his idea to apply business-thinking to healthcare for the poor. We became motivated to launch LifeNet out of a desire to better serve the global poor (and for me personally an entrepreneurial desire to be part of a start-up). Burundi ranks as the third poorest country in the world. In 2005 it emerged from a 12-year ethnic-based civil war that destroyed over 30% of national GDP. The vestiges of its war-torn past are most palpable in the health sector today. Microfinance has done wonders in helping the poor gain sustenance in food, but little has been done in healthcare. In Burundi the infant mortality rate is high: 101.3 per 1,000 live births; also the average life expectancy is low at 50.43 years.

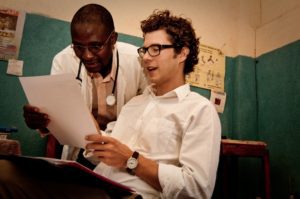

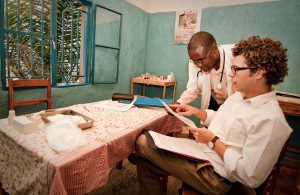

We sought to work within the realities of the Burundi healthcare system by seeking out existing clinics and offering to bring education to them through our franchise systems and in-clinic trainings. When selecting clinics as potential franchises, we have a 4-6 week assessment period where we conduct interviews, make site visits, and collect basic data to understand the clinic’s operational and functional challenges. Also we want to learn what they’re doing really well. We look for operators who are running sustainable clinics prior to LifeNet’s involvement but who face a challenge they can’t solve alone. By running a sustainable clinic, they’ve already self-selected as a competent leader, which reduces a lot of risk on our end. Secondly, we’ve had particular success with church-owned clinics. They serve a vital role in the private health sector here and have good management depth. Church clinics generally prioritize social good first but also aim to run a sustainable organization.

Each clinic benefits differently from our franchise. During the assessment period we try to understand each clinic’s biggest challenges and start there. For some, it may be business coaching and receiving one-to-one advice with our staff. For others, it may be a loan to expand their facilities. Over time, each partner will implement the full franchise of on-going nurse education, business tools, marketing, and pharmaceutical supply (the loans are optional). We’ve tried to create a franchise that addresses the unique challenges of each clinic while using a standardized format that can serve the needs of a great many clinics at once.

Launching a business in Burundi is challenging. Official NGO registration with the government is required to scale your organization, import goods and the like. This process took me 16 months to complete because we refused to pay bribes. I met with everyone from the Minister of Health to the Permanent Secretary of Foreign Affairs to every administrative assistant, I believe, in the entire government (so perhaps not everyone in the government, but I did meet with a LOT of people to gain our final approval). But all the work, all the setbacks, taught me a very important lesson in not giving up.

The challenges ahead are significant. We’re still trying to increase the financial sustainability of our operations through medicine importation, but that’s a very difficult business in a developing country. There are also significant infrastructure and educational constraints that are major problems and not quickly fixed. But it’s incredibly exciting to see our work continue to grow. We’re now in 40 clinics and hospitals in Burundi and our network sees nearly 50,000 patient visits every month! In our first 10 clinic partners (with one year of partnership) we’ve improved the quality of care by 63% on average. In a country of 9 million people, we feel like there’s a real chance to impact their well-being.

For those planning to enter the social entrepreneurship space, I would take Ed Freeman’s class and begin to question the social entrepreneurship heuristic. I think we should start with recognizing the problem to be solved and then trying to understand what forms of capital are required to solve it – is it philanthropic capital, patient capital, economic capital, or something else? There are a number of great nonprofits that apply business-thinking and a (very large) number of great businesses that generate social value and each are solving meaningful problems. If you are interested in solving complex problems using non-traditional capital – philanthropic or otherwise – core business skills are crucial.

Guest author Jonathan O’Connor is rising second-year MBA student at the Darden Graduate School of Business. Prior to Darden, he was a co-founder at LifeNet International, a nonprofit that improves performance of primary care clinics and hospitals in Burundi, East Africa. Prior to launching LifeNet, he worked as an investment analyst with CNL Real Estate Advisors. During his time with CNL, he helped to originate private placement real estate funds for syndication to the retail equity markets. Prior to joining CNL, Jonathan was awarded a fellowship at the Trinity Forum Academy, a leadership academy based outside of Washington, DC. Jonathan will spend his 2013 summer as an associate at New City Capital, a private-equity firm based in Charlottesville, Virginia and Addis Abba, Ethiopia.