A meme that animates these mid-term elections is that we in America have begun an economic “reset,” a downward step-change in our welfare, future, and self-confidence. As the booms in the Internet businesses and in housing have taught us, we should always question “new era” thinking. For similar reasons, “reset” warrants caution.

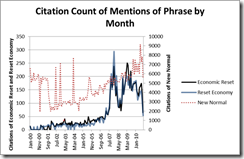

Almost two years ago Jeffrey Immelt, CEO of General Electric, declared the onset of an “emotional, social, and economic reset,” a term echoed by Steven Ballmer, CEO of Microsoft. Mohamed El-Erian, Co-CEO of PIMCO, called it “the new normal.” Many others took up the theme. In a fairly brief frame of time, the concept of a discontinuous change took root within business, government, the media, and academia. The graph nearby shows the number of news articles using these phrases. Mentions skyrocketed after the onset of the Subprime Crisis in 2007.

“Economic reset” might really be useful if we truly understood what it means. My content analysis of recent uses reveals a vague and freighted phrase. In history, true “economic resets” were transformational: big, costly, enduring, pervasive, and surprising. An example of “reset” most typically offered is the Great Depression (1929-1939). Other possible episodes would be the sharp post-World War II demilitarization of 1945-1950, the “Long Depression” of 1873-9, the depression of 1893-1897 and several other instances. These are broad and deep events. Carmen and Vincent Reinhart studied 15 large financial crises and found an average of seven years for deleveraging to run its course. Qian Rong, Carmen Reinhart, and Kenneth Rogoff found that economies can take up to 50 years to recover to a level of activity that prevailed before financial crises that featured bank panics, global scale, and adverse capital flows.

It would make an interesting parlor game or classroom exercise to ask a group of people to look at real GDP data alone and distinguish “resets” from recessions. The United States endured some 20 economic recessions in the 20th Century, and perhaps 20 in the 19th Century. The parlor game would likely reveal that there are as many different assessments of “reset” as there are players.

Two years since, can we all agree that the Subprime Crisis triggered a “reset?” No, not yet. First, the recent events do not map easily onto the depth and severity of the previous resets: with a 3% GDP contraction lasting 18 months, the Great Recession pales in comparison to say, the Great Depression or the “Long Depression” of 1873-79.

Second, the current situation lacks the pervasiveness of antecedents. Nevada and the city of Detroit are devastated; Utah and Washington D.C. are not. Greece, Iceland, and Ireland are plainly in deep distress, but China and India remain buoyant. Industries such as housing, financial services, and print media writhe in pain, but oil & gas, health care, agribusiness, and information technology barely broke stride.

Third, the social and political environment doesn’t compare well to historical examples. We have had rallies in Washington and Tea Party populism, but have yet to see a populist presidential hopeful on the order of William Jennings Bryan (1896), the demagoguery of Huey Long and Father Coughlin (1930s), Coxey’s Army (1894), Bonus Army (1932), the violence of the steel and Pullman strikes (1894) or the Molly Maguires (1875), and long bread lines of the Great Depression. Such kinds of events may yet appear in this cycle, but until they do, how can one be certain that we are now in “reset”? Polls suggest that a political regime change is imminent, though such is not unusual for a mid-term election.

To be sure, present unemployment, low growth, the fragility of the recovery, and the fiscal deficits of the U.S. are serious and unsustainable. They will entail a rather messy correction if not reversed soon. In this sense, the events of 2007-2010 may better be labeled a “preset,” precursor to a much bigger realignment that awaits the U.S. economy if fundamental problems remain unaddressed.

The power of “reset” may be its usefulness to leaders in mobilizing constituencies at both ends of the political spectrum. The Left has harnessed this meme to motivate a stimulus funding program, health care reform, and re-regulation of the financial services sector. On the Right, the meme underpins a spirit of regime change displayed by Tea Party and Libertarian candidates who argue that most of what the government does is unaffordable now and in the years ahead. Thus, the meme has influence in the way that Humpty-Dumpty told Alice in Through the Looking-Glass:

‘When I use a word,’ Humpty Dumpty said, in a rather scornful tone,’ it means just what I choose it to mean, neither more nor less.’

‘The question is,’ said Alice, ‘whether you can make words mean so many different things.’

‘The question is,’ said Humpty Dumpty, ‘which is to be master – that’s all.’