“Teaching is like sending a letter with an imperfect address. You never know where or when the message will arrive.” — C. Roland Christenson.

Christenson, a mentor of mine, passed away years ago; but lives on in my memory for wisdom such as this. A recent experience would prompt me to modify it to say, “You never know when or where the message will be sent or delivered.” This modification speaks to the choices teachers make and to the role of chance and serendipity. Consider the experience I had last month.

It began with an email in October from Christina Feng, a teacher at Martin Luther King High School at 65th and Amsterdam in New York City. She wrote,

“Dear Dean Bruner,

I’m a Teach For America alumna teaching high school business, economics, and government to disadvantaged, at-risk 12th graders. I love what I do, and this year, to better facilitate my students’ understanding of the business world, I am having my students run a boutique mergers and acquisitions advisory firm. We are just in the beginning stages of our work, but we are getting very into it. I am writing to see if we could welcome you as a guest in our classroom…I want to show my students that they deserve the attention of talented and successful people like yourself, and that they too, can enter the world of finance, no matter what their own personal backgrounds may be. I look forward to your thoughts.

All the best,

Christina Feng

P.S. I’m requesting funding through Donorschoose for a class set of your book, "Deals from Hell." Any and all help spreading the word would be appreciated!”

Christina’s invitation grabbed my attention. First, helping disadvantaged kids finish high school has to be a national priority. Failure to get a diploma is a key predictor of adult poverty. [For more on poverty and its drivers, see, Creating an Opportunity Society, by Ron Haskins and Isabel Sawhill.] I’ve done my share of criticizing K-12 education in the U.S.—so, I thought that this might be an opportunity to lend a hand and at least learn more.

Second, I was surprised by Christina Feng’s audacity. Running a simulation of an M&A advisory boutique with a group of disadvantaged kids? Assigning them to read my book Deals from Hell, which is clearly written at a collegiate level? Asking me to fly to New York, teach, and fly home? Plainly, her “knock and the door will open” attitude contradicted some widespread (and often wrong) characterizations of public school teachers.

Third, it sounded like fun. Christina has a lot of energy for her students—indeed, she is a nuclear stockpile. I like the company of such people and don’t mind picking up some spare radiation. Would it be humanly possible to teach anything meaningful about M&A in a 90-minute class to 12th-graders? One disability of all “experts” as teachers is that they know too much. I can talk for hours about the technicalities of M&A. The challenge to speak plainly and concisely is a wonderful opportunity to grow.

Therefore, on February 16th, I found myself in Christina’s classroom. I had suggested that we teach by the discussion method rather than by lecture. I shared with her some merger negotiation exercises that we use at Darden. She offered to develop a new simulation, based on the hypothetical acquisition of the New York Times (NYT) by Google.

Simulations are complicated and take a long time to develop. But Christina pulled it off. She developed a narrative for the companies and the negotiations. And she directed her students to some online sources of data. She formed the students into three bargaining “worlds” where each world consisted of one team representing Google and the other representing NYT. And she set aside plenty of time for the students to prepare for the negotiations and then to bargain. Finally, she had the students read a few chapters from Deals from Hell (one copy for each student, kindly donated by my publisher, John Wiley & Sons.) Thus, when I walked into her class, the students were pretty well steeped in the exercise and ready to talk about their experience.

After introducing ourselves to each other, I went from world to world, asking the students to describe the negotiations and their result. All three worlds reached agreement. The work in each world showed reasonable analytics (mainly based on P/E ratios) and strategic thinking. Especially interesting was the fact that in two worlds, the buyer (Google) agreed to a price that exceeded its reservation or “walk-away” price. I probed. We learned that the seller, NYT, “anchored” the negotiations by quoting a very high asking price at the outset. This led to more questions about how human behavior (both the strategic kind and the unintended kind) can influence negotiation outcomes. With the analytics and the behavioral considerations in mind, we began to consolidate an image of M&A as a very messy, risk-prone affair. As we discussed the risks in the Google/NYT combination, the students asked me about the Deals from Hell. This gave a natural segue into closing comments about success and failure in M&A and about the students’ future.

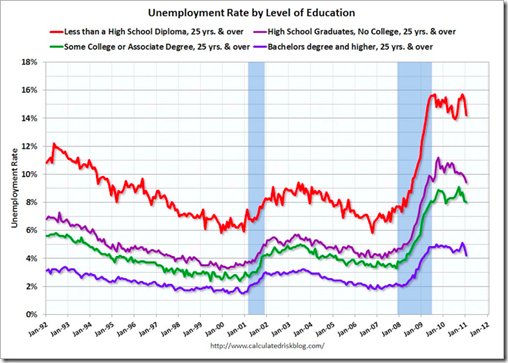

As a coda to my class, I urged the students to finish high school, get the diploma, and go as far as they can up the educational ladder. If they are assured of graduating, I urged them to help someone who is faltering. I said that there is a very strong correlation between educational achievement and economic welfare. One example I mentioned was the evidence contained in the following graph (provided by the folks at Calculated Risk.) It shows a clear association between unemployment and level of education attained.

I urged the students to get more education: vocational school to learn a trade; an associates degree at a community college; and/or a four-year bachelor’s degree. I said that money should not hold the students back—there are sources of loans and financial aid. The intellectual challenge should not hold them back—there are tutors, advisors, and other sources of support that can help. Time should not hold them back—it is possible to find part-time educational programs. Sure, it is hard work. But there is no free lunch. If you want to make a better life for yourself, you must make the investment. I said that now is the time in their lives to reach for the brass ring: don’t wait.

The students applauded. Many of them asked me to autograph Deals from Hell, (catnip to an author). Afterward, Christina and I went to a quick lunch—she insisted on paying for my salad; I insisted back; she insisted harder. We said goodbye; I hustled back to the airport to catch the plane home. But like the aftermath of any good case discussion, the process of reflection for me continues.

This felt like time well-spent. I helped to deliver a message consistent with Darden’s values about reflective learning, excellence, hard work, and diversity to a group of high school students at a moment when they are looking for role models and wrestling with their futures. I think we actually succeeded in conveying some important ideas about M&A. And it was a great deal of fun. Check out this photo: these kids have personality. (So does Christina, at the extreme right.)

The ultimate test of the worth of a class is whether students learned something important. I’ll never know for sure; this is the existential uncertainty of any teacher. As my mentor said, it’s hard to know when and where the message will arrive—and as I would add, it’s hard to know precisely what messages were sent. When it comes to promoting learning, how you are teaching can be as important as what. It sure seems to me that the simulation and class discussion really nailed a how. I saw a wonderful high school teacher who thought deliberately and audaciously about a variety of ways to send important messages. Christina Feng is an inspiration and gives me hope for the future of public K-12 education in the United States.

And to the students in Christina Feng’s class: YOU RULE!