“Maybe it’s time to ask a question that seems almost sacrilegious: Is all this investment in college education really worth it? The answer, I fear, is that it’s not.” — Megan McArdle, Newsweek September 17, 2012

“Right now, I would pay $100,000 for 10 percent of the future earnings of any of you…Many of you are a million dollar asset right now.” – Warren Buffett to a group of MBA students.

Well, there you have it: the gist of a debate over the value of higher education. Some say high; some say low. The media have been loaded in recent months with angst about student loan debt. By any absolute standard, this is a big exposure. The default rate on student loans has spiked to 13.4% for graduates of the class of 2009. Mounting student debt triggers a great deal of finger-pointing: it is claimed that universities charge too much; employers aren’t making jobs available for graduates; the government isn’t doing anything to help; the students didn’t know what they were getting into; and bankers are heartless in throwing hapless borrowers into bankruptcy.

Finance 101 teaches that the simple availability of credit should be irrelevant to anyone’s decision about borrowing. Instead, the dominant consideration should be the attractiveness of the purpose to which the borrowed funds will be put, compared to some benchmark. “Attractiveness” can be defined in a host of ways—the economic test of attractiveness would be whether the return on an investment in higher education exceeds the cost of funds to finance it. It could be that all those student borrowers acted sensibly to invest in their own human capital. Thus, the dominant question should be, does higher education pay? Does it yield a sufficient rate of return to service debt and leave something over to lift the student’s standard of living?

The return typically exceeds the cost of financing

Plenty of evidence suggests that the payoff from investing in higher education is large. The longer answer is “yes, if…” the student borrower is a careful and critical consumer of loans and educational services. To understand the general conclusion and some nuances, let’s look at research findings.

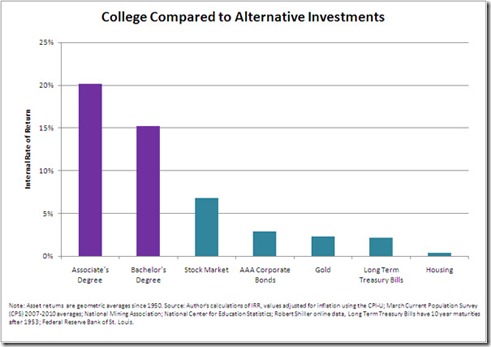

Academic studies find that the returns from investing in one’s education are very high, well exceeding the returns that consumers might conventionally enjoy on a range of investments. Generally, research finds real rates of return on investment upwards of 10% and as high as 50%. ((See four studies: Card, D., 2001. “Estimating the Returns to Schooling: Progress and Some Persistent Problems”, Econometrica, 69(5), 1127-1160. Palacios-Huerta, I., 2003. “An Empirical Analysis of the Risk Properties of Human Capital Returns”, American Economic Review, 93(3), 948-964. Psacharopoulos, G. and H. Patrinos, 2002. “Returns to Investments in Education: A Further Update,” World Bank discussion papers 2881. Heckman, J, Lockner, and P. Todd, 2003 “Fifty Years of Mincer Earnings Regressions” http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=410658.)) Most recently, the Brookings Institution released a report in which they actually calculated the ROI on a college education—they did it in the right way, including the cash outlays and foregone earnings while in college as the “investment.” They summarized findings as follows:

Higher education is a much better investment than almost any other alternative, even for the “Class of the Great Recession” (young adults ages 23-24). In today’s tough labor market, a college degree dramatically boosts the odds of finding a job and making more money. On average, the benefits of a four-year college degree are equivalent to an investment that returns 15.2 percent per year. This is more than double the average return to stock market investments since 1950, and more than five times the returns to corporate bonds, gold, long-term government bonds, or home ownership. From any investment perspective, college is a great deal.

The Brookings report continued,

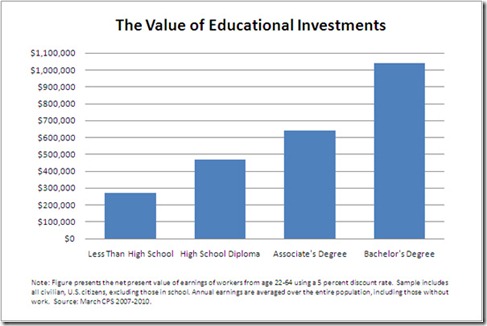

Another way to view the total dollar benefit of a four-year college degree is to compare the cumulative lifetime earnings of workers based on their educational attainment—as shown in the graph below. Through this lens, a bachelor’s degree clearly provides the largest boost to earnings. Over a lifetime, the average college graduate earns roughly $570,000 more than the average person with a high school diploma only—a tremendous return to the average upfront investment of $102,000 investment. An associate’s degree is worth approximately $170,000 more than a high school diploma.

And other benefits amplify the return on investment in higher education

And the ROI could be higher yet. Maybe the ROI estimates ignore unquantifiable effects from an investment in higher education. The estimates of return understate the benefits if, as seems likely, any of the following benefits obtain:

· Greater career flexibility. As we see at the Darden School, our degree programs help career switchers—both at the point of graduation and later in life because our students have been trained in a variety of functional fields of business. And a degree helps you in any horse-race with other applicants for a job: higher education signals the ability to learn new skills presently and in the future. Michael Spence won his Nobel Prize in Economics (2001) based on his research finding that higher levels of education signal rarer capabilities to prospective employers. Education creates career options, flexibility that can help you find more fulfilling and remunerative work. Business education in particular can help you anticipate risks and errors in starting new businesses, developing new products, and helping firms grow. Given the conventionally high rates of business failure, it would seem that professional training certainly beats the alternative, the “school of hard knocks.”

· Higher quality-of-life. Research shows a positive association between higher levels of education and health, civic engagement, family stability, and a negative association with ills such as crime and addiction.

· Higher prospects for social mobility. The growing “income gap” between the more and less affluent is associated with level of education. Robert Reich wrote in The Work of Nations: “The widening gap between rich and poor seems to be related to a growing divergence in how much money people receive for the work they do. And that divergence, in turn, appears to have something to do with their level of education. If you graduated from college, your earnings improved. If you did not, and especially if you were male, you got poorer. Further, the trend is not limited to the United States; it is occurring in many other places around the globe.” (p. 207)

· Growth in wisdom. Aristotle said, “knowing yourself is the beginning of all wisdom.” Perhaps the association between education and higher quality of life is due to self-knowledge acquired in higher education: an accelerated maturity in judgment, refinement of values, a deepened sense of personal honor, growth in the capacity to think critically, and increased clarity about purpose. Higher education simply prepares one to function more effectively in the face of life’s uncertainties. William Lewis, in his important book The Power of Productivity, wrote, “Education is the organized system for helping the members of a society to understand themselves and the world in which they live. It’s not the only way. Simply living accomplishes much of this. However, education, at least theoretically, is much more efficient. Through education, we learn the lessons of the past. Through living we learn only the lessons that current experience can teach us.” (p. 307)

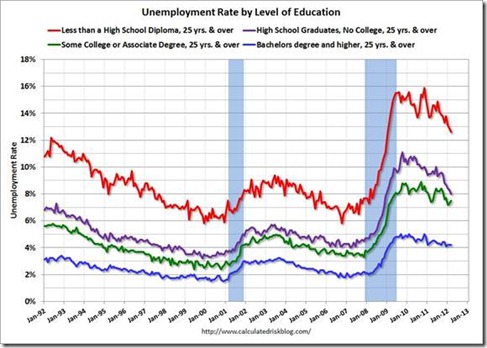

· Reduction in risk of unemployment. This may be the most obvious un-quantified benefit from an investment in higher education. The Brookings report acknowledges that its own ROI estimates are not adjusted for the risk of unemployment. Education provides a valuable hidden option that helps to act as a shock absorber, like an insurance policy, against the episodic employment shocks that business cycles impose. The higher-educated are out of work less often. Today, the unemployment rate for college graduates is 4.1%, about half the rate for the whole U.S. population. This finding is robust across time—see the following graph.

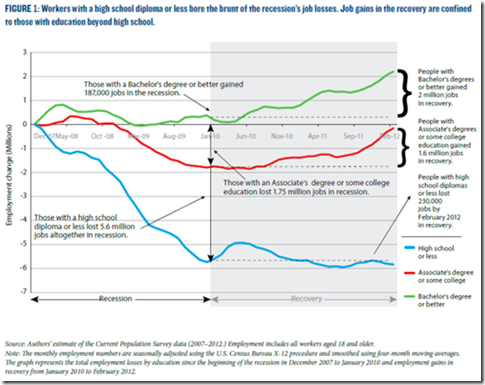

A report by Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce finds that the recession starting in 2008 hit the less-educated disproportionately harder:

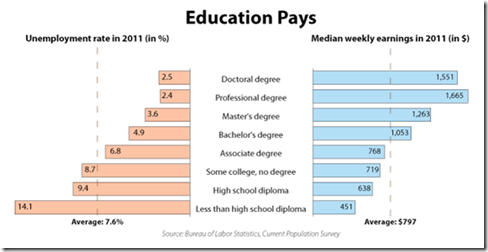

Data from the Current Population Survey prepared by the Bureau of Labor Statistics shows that graduate degrees typically yield a higher return and even lower unemployment:

Specifically regarding MBA degrees, a recent Forbes posting commented,

According to The Economist, employers typically pay MBA graduates twice as much as those with bachelor’s degrees, and about 35 percent more than those who earn Master of Finance degrees. The wage loss that has been experienced by millions of American workers has not been too pronounced for MBA graduates. Considering the economic damage sustained by the U.S. workforce, MBA degrees can be thought of as truly being “recession-proof.”

I have not seen a value placed on this insurance effect. But given that the insurance is long-lived and apparently so reliable, its value is probably high.

Now for some critical thinking

The findings presented so far are pretty consistent: the ROI on higher education is high. Why might this dream not come true for someone in particular? Consider several factors that can affect the ROI:

· The average ROI may not be a good predictor of likely outcomes. The discussion so far has focused on large-sample findings and generalizations from experience. Maybe the ROI estimates are averages drawn from a wide and skewed distribution: perhaps a few graduates of elite schools get really high salaries and these graduates pull the averages up, while most other graduates don’t fare so well and never realize the average ROI. The average starting salary of MBA graduates is roughly associated with the ranking position of the school. The AACSB says that there are some 13,000 institutions in the world that award higher degrees in business—do all of these produce golden apples?

· Maybe times have changed. As the advertisements say, past performance is no guarantee of future outcomes. Megan McArdle and Tyler Durden suggest that we are in the late stage of an educational bubble—not unlike the housing bubble—that will lead to a crash in the value of higher education. But the research on the ROI to education covers longer time-frames that include booms and busts. Even if there is a bust in the near future, one faces a lifetime over which to harvest the benefits of education. With the benefits of modern medical technology, the student today could be looking at 60 years of productive application of one’s education. To say that education won’t pay sometime in the future is quite a stretch. As Sir John Templeton said, “The four most dangerous words in investing are ‘This time it’s different.’”

· Personal choices. For instance, the choice of undergraduate major is associated with an enormous range of starting salaries right out of college. PayScale offers some data on this: from low to high is more than a 3X variation. Average starting pay for theology majors is $32,500; for petroleum engineers, it is $98,000. Other choices affect future earning power: where to live; which industry to work in; and which field you chose for training. Higher education opens doors; it doesn’t make you choose which door or dictate the speed with which you walk through.

· Other stuff drives success too. In addition to level of education, think of all the other influences on one’s career success: work ethic, integrity, “people skills,” mentoring, and social upbringing. Luck plays a huge role: for instance, the business cycle annually creates thousands of stories of “being in the right (wrong) place at the right (wrong) time.” One’s initial job right out of college has a strong association with future earnings. The PayScale data show that starting salary explains 78% of the variation in salary at mid-career in the same industry.

Given this list of factors, it seems inevitable that the ROI from an investment in education is bound to differ from the average result. Higher education is associated with certain good outcomes; but no law says they will occur.

Conclusions

Higher education pays, conditional on the critical thoughts mentioned earlier. The higher you go up the educational ladder, the more it pays. Even getting just some higher education pays: an associate’s degree or even a year of college can lead to higher earnings and less exposure to the risk of unemployment. If Warren Buffett—the so-called “world’s greatest investor”—sees a fair trade of education expense for a claim on future income, the return on higher education must be real. Lumni, co-founded by Darden graduate, Miguel Palacios, extends educational financing in return for a participation in future earnings.

But I offer four cautions to the prospective student:

· Higher education may not be for everybody. You have to be ready to make a sacrifice for your degree: it takes time, money, and great effort. And it takes the academic preparation and intelligence to do the work—Charles Murray has made much of this in arguing that too many people are going to college. If you have doubts about your readiness for higher education, a candid chat with an educational counselor should clear the air. My recommendation: if you have the preparation and the gumption to study, get as much higher education as you can.

· Consider the alternatives. There’s vocational training to learn a craft. The military can teach you a great deal about self-discipline and devotion to the team; but if you want to become an officer, you’ll need a college degree. Or you could start a business—venture capitalist, Peter Thiel, has been paying high school graduates not to go to college, but to become entrepreneurs instead. But with 19.7 million students enrolled in colleges and universities in the U.S., keeping up with your peers will have a strong appeal.

· Be a wary consumer. Think critically about what you are investing in and the benefit you can hope to receive. These days, students give great attention to their vocational preparation. Learning to reason and communicate well and building your social and moral awareness are hugely important to success in just about any field. So don’t ignore the liberal arts. Instead, focus on the quality of the learning experience you will have. Is the school accredited? Is the school selective? You will learn a great deal from the students around you, so consider what they have to teach you.

· Have faith. Focus on getting an education, not just a job. It is absolutely wrong to think of one’s education as a short-term financial transaction. What you put in is clear; what you get out is less clear but likely to prove a powerful advantage over time. Paradoxically, those students most focused on the immediate gives and gets are most likely to make poor decisions about what and where to study.

The high rate of student loan defaults in the U.S. is a tragedy, a sad corrective to poor decisions by students and aggressive recruiting by diploma mills. Research is shedding light on predatory sales practices at diploma mills that prey on the unsophisticated aspirants in higher education. Those practices are wrong. Sunlight is the best disinfectant. No doubt, lawsuits and government investigations will prompt more regulation. Meanwhile the best protection is very diligent research, assessment of alternatives, and critical thinking about what you give and get.

But the current angst over the currently high student loan default rate should not obscure the well-documented fact that, on average and over time, achieving an education can yield massive benefits to the individual. For most people, borrowing to get a degree will be worth it.