But I think of it as a factory.” — John Reed, EVP, Citibank, circa 1975 ((Quoted in R. B. Chase, Handbook of Service Science, Paul, P. Magio, Cheryl A Kieliszewski, James C. Spohrer, eds.))

I once worked in a very large bank for the SVP who ran all of the back-office operations. In those days (the 1970s) banks were just commencing the vast wave of automation that continues to this day. My boss was not a jovial relationship banker nor an aggressive deal-doer; he was a cool engineer. And, like John Reed, his mission was to improve efficiency. He saw not a bank, but a factory. Information technology was his instrument for change. I observed the very rapid changes induced by automation and information technology. This experience impressed me with the power of innovations in processes and services. Though one may like to think of financial innovation in terms of markets, institutions, and instruments that the individual can see, the out-of-sight/out-of-mind innovations in processes and services may well be the most significant.

Ubiquity. The “back office” innovations in financial services are significant because they are everywhere and ongoing almost continuously. The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies by Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee tells a sobering story about the inexorable advance of automation and process improvements through artificial intelligence, big data, machine learning, and so on. If you think you are somehow exempt from this trend, think again. And look around you: recently, you’ve probably used one of the most important financial process innovations:

· Automated Teller Machine (ATM). Since introduced in 1965 in the U.K., and in 1969 in the U.S., the ATM has grown to some 2.2 million units installed around the world. The machines, originally designed to dispense cash, now handle a range of routine functions that might have otherwise entailed a human teller, including bill paying, money transfers, deposit acceptances, updating passbooks, purchasing tickets for movies, concerts, lotteries, and trains, and donating to charities.

· Automated Clearing House. Clearing houses were initially founded as associations among banks, at which the daily exchanges of checks and money were made. The first clearing house in the U.S. was established in New York in 1853. In the early 1970s, bankers decided to automate the daily bank clearings because of the enormous growth in volumes that threatened to overwhelm the legacy processes. The National Automated Clearing House Association (NACHA) was founded in 1974 to integrate and standardize the clearing technology. NACHA reported, “Each year it moves more than $40 trillion and nearly 23 billion electronic financial transactions, and currently supports more than 90 percent of the total value of all electronic payments in the U.S. As such, the ACH Network is now one of the largest, safest and most reliable payment systems in the world, creating value and enabling innovation for all participants.”

· Point of sale transactions. Advances in hardware and software have helped to integrate the retailer with the financial system, eliminating time-consuming and costly handling of paper, credit card information, and records of sales.

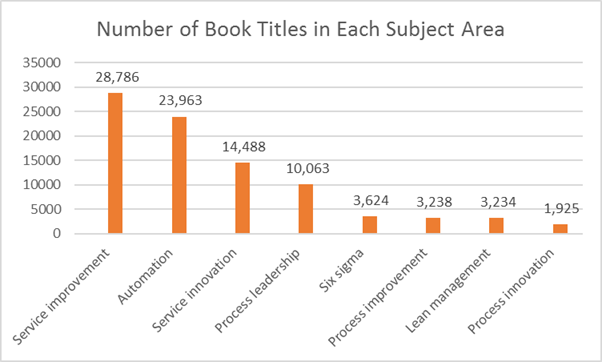

If what I saw in the 1970s was a “wave” of automation, we have today by comparison a “tsunami” of automation, prompted by artificial intelligence, big data, machine learning, and device-driven guidance. My colleague, Ed Hess, has published a new book, Learn or Die: Using Science to Build a Leading-Edge Learning Organization, that describes this phenomenon in more detail—I recommend it. And the advent of blockchain technology is all about process improvements. Suffice it to say, financial innovation in services and processes is a very big deal. The literature on topics in the area of automation and process improvement is vast. A casual search on Amazon.com summons up thousands of book titles:

Therefore, it is impossible to summarize in a couple of days (or even a semester) what the general subject area entails. But the focus this week was on a few ideas that are relevant to financial innovation and fintech today. I sought to motivate these ideas with a selection of readings that deal with credit rating practices and the diffusion of new processes in the insurance industry.

Credit processes and credit growth. The article by Rotheli described the rise in the 1920s of new credit risk evaluation methodologies. “Credit barometrics” were based on quantitative measurement of a prospective debtor’s creditworthiness. Before the 1920s, a debtor’s character, capital, and capacity were the largely qualitative foundations of a credit decision. The introduction of credit barometrics in 1919 triggered a movement toward the algorithmic assessment of risk—the parallel to the rise of credit algorithms in today’s fintech should not be ignored. Ratios derived from the financial statements of borrowers produced objective measures that could be compared to averages for industries. This permitted objective judgment and differentiation among industries. These ratios would be updated over time to produce current standards. And the multidimensionality of the ratios was resolved by producing a weighted average across all the ratios (the weights were produced by “experimentation,” whatever that means.) All of this amounted to “scientific management” consistent with the Progressive Era impulses running through American culture at the time. Rotheli argues that the advent of credit barometrics permitted credit assessment on a large scale, allowing for the processing of more credit applications and perhaps encouraging banks to market their lending capabilities and expand credit. But the algorithm did little to warn of the dangers of the credit expansion, leading to the Great Depression.

Clusters and waves of process innovation. The article by Robin Pearson helps to illuminate the “clustering” in time, industry, and geographic location that one can observe in process innovation. Economic clusters have been a hot topic for a couple of decades. In The Competitive Advantage of Nations, Michael Porter argues that geographic clusters of industrial leadership provide the basis for national advantage. [Note to yourself: if you want to join a really high-performing firm, you are more likely to find it in a cluster.]

But this article by Pearson prompts us to consider clusters in time: why do process innovations tend to come in waves? Famous economists such as Schumpeter, Kuznets, and Rostow discussed the cycles of innovation and the tendency toward the batching or lumpiness of process innovations. Batches of process innovations prompt costs to fall, processes and products to conform to new standards, then rising competition, falling investor returns and competitiveness—all of which stimulates a new wave of innovations. ((Pearson, page 236.)) But in his study of innovations in the British insurance industry in the 18th and 19th Centuries, Pearson finds a different cycle: new products are introduced, followed by waves of incremental and then radical process improvements, and ultimately extended to mass markets. ((Pages 248-9.))

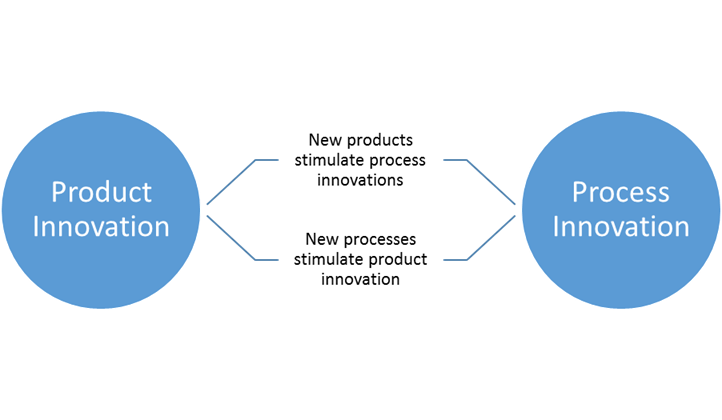

The big idea here is that product innovation and process innovation interact and complement each other. A wave of new products stemming from a technological breakthrough is likely to be followed by a wave of incremental and then radical process innovations.

An example of this interaction would be the introduction of charge cards and credit cards (new products) in the 1960s that stimulated the introduction of automated teller machines (new processes) in the 1970s, which in turn stimulated the introduction of debit cards (product) and eventually stimulated the development of point-of-sale terminals (process) for the integration of retail and financial systems in the 1980s and 1990s. Underlying this interaction between new products and new processes is technological development, though Pearson also notes that changes in markets and big events (such as natural disasters or epidemics) can stimulate process innovation. Pearson notes a correlation between the size and growth rate of a firm and the rate of its innovation—he says that this may derive from economies of scale. Earlier in the course, we read research that suggests large institutions are prone to introduce innovative products and processes.

By now in the course, you should be starting to make some connections among the dots. We have seen repeated examples of innovations in some areas of finance stimulating innovations in other areas. Innovations in markets, institutions, instruments, services and processes, tend to spark each other. And if repetition is the first principle of learning, then the repeated appearance of the main drivers of innovation should have helped you lock them in mind: profit-seeking, risk management, regulation, inefficiency, incompleteness, and others appear repeatedly in our exploration.

Modern algorithms, finer detection of risk. We were visited by Jerry Nemorin, D’08, founder of LendStreet, which assists distressed borrowers with restructurings of their debts, education in financial literacy, and loans. Nemorin said that banks charge off $25-40 billion in credit card losses per year. For loans over 90 days delinquent, banks are willing to take a 50% “haircut,” which LendStreet shares with the borrower to reduce the burden. LendStreet funds the settlement with the bank, giving the bank faster payout than obtainable through a bankruptcy process; in turn, LendStreet gives the consumer a better repayment plan (typically a smaller payment). Then it sells the loans to investors, who obtain an ROI of 14-15%. A better credit algorithm than the banks had makes this possible. Nemorin developed a proprietary credit analytic system that focuses on “ability, capacity, and intent”—LendStreet looks to help the borrowers who are not genuinely insolvent, but who may be illiquid because of an emergency or other shock that disrupted their debt repayment plans. He says that LendStreet seeks to help borrowers who have good financial stability, an “old middle class profile.” The average age of the consumers they help is 55. The average FICO score is 580, which is unattractive to most lenders. But Nemorin said that “FICO works imperfectly.” It is a “one size fits all” credit score that ignores important circumstances of the borrower. LendStreet has less than a 5% default rate, while the average default rate for FICO scores around 580 is 18-20%. “We go after a segment who are going to perform; we are picking the fallen angels,” said Nemorin. This is an example of a financial entrepreneur seeking both to complete the markets and bring greater efficiency into the pricing of assets in those segments of the markets.

Process innovations may create path-dependency. Frank Partnoy wrote about “the tendency [of financial innovation] to outstrip the ability, and perhaps the willingness, of investors and intermediaries to process information…Information asymmetry in financial markets tends toward cyclicality: as financial innovation builds, so do disclosure gaps and misunderstandings.” Credit-rating agencies are viewed from two different perspectives. One view sees the agencies as gatekeepers who issue credible information because not to do so would damage their reputations. The other view holds that credit-rating agencies don’t issue information, but rather, “regulatory licenses,” which are the right to be in compliance with regulations that restrict the kinds of securities in which pension funds and other institutional investors might place funds. These regulatory licenses breed “behavioral overdependence” on credit ratings and the kind of excessive and uninformed investment in new financial instruments. Partnoy illustrated this thesis with the example of Ivar Kreuger in the 1920s and 1930s. “Overdependence on credit ratings has a behavioral element, which is highly path-dependent and has become deeply embedded in investor culture. It is expressed not only in regulation, but also in privately created investment guidelines and policies and the extensive use of credit ratings in financial contracts.” ((Page 438.)) This overreliance began after the onset of the Great Depression: the U.S. Treasury Department and Comptroller of the Currency required ratings from two agencies to establish the quality of a bank’s bond holdings: issues rated BB or lower would have to be completely written off. Over time, the role of credit ratings in serving “regulatory license” grew. Thus increased the distance between the investor and the investment: in the mid-2000s, it mattered less to know exactly what kinds of mortgages were in a collateralized mortgage obligation (CMO) than what the credit rating agencies thought of it. In hindsight, it is clear that the credit rating agencies did not fully understand the risks embedded in the CMOs and other new instruments. As Partnoy argues, financial innovation outstripped sound practice.

Diffusion. How “best practices” spread among financial service providers lends insight into the diffusion of innovations through a market. The speed with which innovations spread through an economy help to determine the financial and social returns on innovation. Who adopts these innovations, and why? The article by Akhavein, Frame, and White looked at the adoption of small business credit scoring practices by banks. Credit scoring is one of the foundational activities is banking. It is used to determine whether to lend to a prospective borrower, and if so, what interest rate to charge. The study found that “larger banking organizations introduced innovation earlier, as did those located in the New York Federal Reserve district.” Studies of the diffusion of automated teller machines (ATMs) have found similar results. What’s going on? First the adoption of innovations can be expensive. Therefore, it helps to have a large capital base with which to run alpha and beta tests—this might explain the significance of the large firms in diffusion. Second, the concentration of diffusion within the large money centers could be attributable to the typically intense competitive environment there. Process innovations are stimulated by a push for efficiency.

Can you manage the diffusion of process innovations into your firm or through an industry? If innovations occur in waves, they seem to have the attributes of fads, manias, or epidemics. Epidemiologists (and sociologists) describe the spread of an epidemic (or social mania) as driven by three factors: a hearty virus or bacterium (or an idea), a carrier (an advocate or influencer), and a receptive host. This suggests three sets of considerations for the process manager in a financial institution (or a fintech entrepreneur trying to sell an innovation):

· How hearty is the idea? “Hearty” should be defined as consequential and proven by research to generate results.

· What is the channel of adoption? Where did the idea originate? How original is it? Who is advocating the adoption of this process innovation?

· How receptive are we? Does this innovation resolve a need? If so, for whom? How?

In our first week of this course, we introduced ourselves to blockchain technology—it remains in relative infancy, but seems likely to spawn a range of process innovations. The blockchain has the potential the automate, accelerate, and improve the quality and security for a wide range of financial products and services. To date, fintech entrepreneurs seem to be using blockchain for innovations in payment systems and account management. Some blockchain-related trends to watch for include:

· Innovations to promote the interoperability of systems, to provide seamless integration and reduce costs.

· Incorporation of the cloud into processes in ways to increase the agility of operations and reduce costs.

· Monetization of the flood of data arising from point-of-sale technology and matched with financial account data. And a rising focus on data quality.

· Strategies to “skim” the most attractive customers for special attention.

· Heightened concern for cybersecurity and data privacy.

Questions for innovators in new financial processes and services:

1. What is the problem that this new process or service solves? How does the new process or service solve this problem better than the older legacy systems? From what one sees happening in the fintech world, the benchmark of comparison should not only be the incumbent processes, but rather, the best new processes available in the markets.

2. Will the process innovation enhance flexibility or reduce it? As most big banks found in the automation wave of the 1970s, the selection of a particular process regime made it very difficult to switch to another one, if market conditions or new technology dictated the shift.

3. Diffusion: virus, carrier, host. If the diffusion of process innovations is “viral” like an epidemic, then one could manage the review and adoption of the innovations with the perspective of an epidemiologist. How significant is the new process (the “bug”)? Who is recommending it (the carrier) and what has been their experience with it? Can this innovation solve actual needs, or is this just a “nice to have” (how receptive are you as a host)?