This post continues a commentary on readings about the Great Depression. For the third meeting of our seminar, Richard A. Mayo and I assigned three readings: The Great Crash by John Kenneth Galbraith, The Memoirs of Herbert Hoover: 1929-1941; The Great Depression, and a segment of Freedom from Fear by David Kennedy. The aims of this session were to study the onset of the depression itself (1929-1933) and to consider critically the early dynamics of the Depression and its causes. Three questions were the special focus of our discussion:

· Did the Crash of 1929 cause the Great Depression? If not, what did cause it and when did the Great Depression begin?

· What other events marked the descent into the Great Depression?

· How did President Hoover respond?

The Crash of 1929 and Beginnings of the Great Depression

Our last two sessions looked at the end of World War I, war reparations, technological innovation, and the wave of deflation that swept the U.S. and other countries in the 1920s. In the popular mind, the Great Depression began with the stock market Crash of 1929—indeed, many people seem to think that the Crash caused the Great Depression. As I’ve outlined in earlier posts, exactly when the Depression began depends on what you mean by “begin.”

The National Bureau of Economic Research (a not-for-profit organization of economists) is the accepted authority on defining the starts and stops of economic cycles. They determine that the downturn that is regarded as the Great Depression occurred in two waves: August 1929 to March, 1933 and May, 1937 to June, 1938. We will look at the second of these downturns in the spring semester.

As regards the first downturn in the Great Depression, a cyclical downturn was probably dictated by the Fed’s increase in interest rates in January, 1928. At the time, the Fed was worried about excess liquidity stimulating a stock market bubble. By January, 1929, economic conditions were starting to deteriorate. In June, 1929, business production peaked. The NBER tells us that a decline began in August, before the stock market crash of October, 1929.

A recession is shorter and shallower than a depression. Our readings for this session suggest that the conversion of a recession into a depression was the result of many factors. Still, did the crash trigger the depression, or was it a consequence? The economic record suggests that it was a contributor, a turning point, but not the sole cause. David Kennedy wrote, “The disagreeable truth, however, is that the most responsible students of the events of 1929 have been unable to establish a cause-and-effect linkage between the Crash and Depression.” (Page 39.) Kennedy reports that 97.5% of the U.S. population owned no stock in 1929. Thus, the impact of the crash must have been small in terms of the direct “wealth effect.” But it seems to have had a great influence in the psychology of consumers, investors, and leaders in business and government. The evaporation of equity value would prompt investors to cut spending and hoard their remaining wealth. The extent of the wealth effect remains a matter of debate, though Galbraith wrote that it had a “traumatic influence on production, income and employment.” (Page ix.)

By the way, the “Crash” was only part of a larger destruction of equity market value. The following figure shows that the initial slump from September 5, 1929 (when Roger Babson warned that “a crash is coming”) to November saw the Dow Jones Industrial Index fall from 381 to 210—a decline of 45%. But from November, 1929 the sell-off continued until July, 1932, sending the Dow from 210 to 42, a decline of 80%. Overall, the decline from 381 to 42, was a decline of 89%.

Figure 1. Dow-Jones Industrial Average, 1929-1932

Source: Macrotrends at http://www.macrotrends.net/2484/dow-jones-crash-1929-bear-market

The Decline

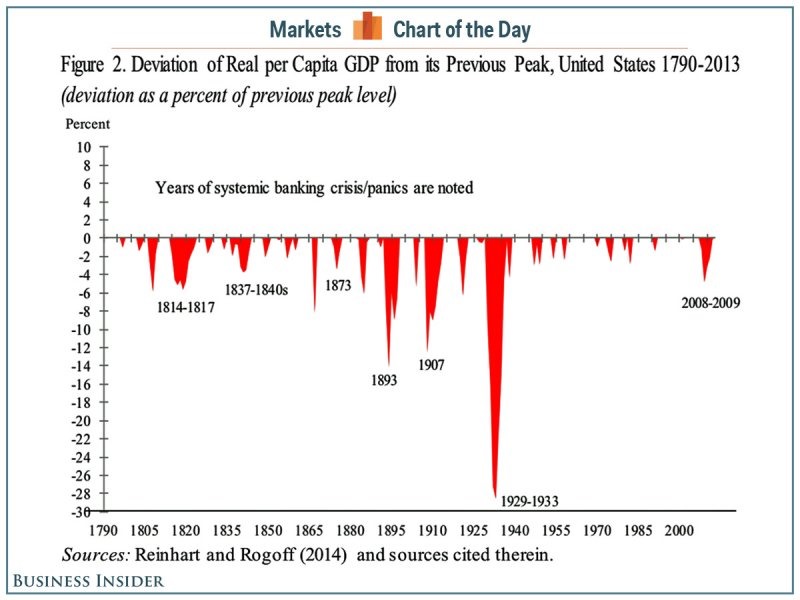

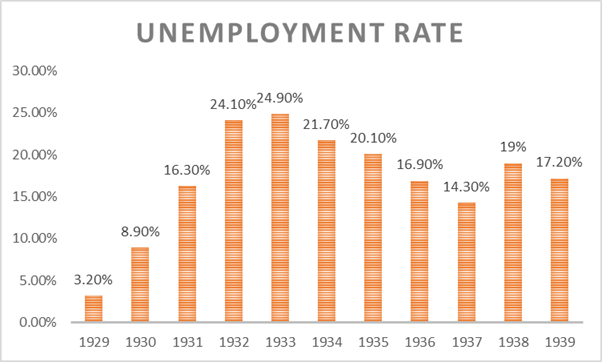

Similar to the stock market decline, the decline in economic activity worsened steadily over four years. Galbraith called the economic decline that began in the summer of 1929 “the beginning of the familiar inventory recession.” The NBER estimates that downturns last about 18 months on average. What prolonged this? What drove it so deep? The severity of the depression is displayed in the next two figures. Figure 2 shows that the Great Depression collapsed Gross Domestic Product far below the normal capacity of the economy. Figure 3 shows that unemployment peaked at about 24%.

Source: Business Insider at

http://www.businessinsider.com/how-real-per-capita-gdp-fell-during-crises-2014-1

Figure 3: Unemployment Rate, 1929-1939

Source: Author’s preparation from data at http://www.shmoop.com/great-depression/statistics.html.

As we deepen our understanding of the Great Depression, it seems that its severity draws from many factors that seemed to reinforce each other. Our readings for this session offered three authors’ perspectives.

Galbraith attributed the crash and severity of the Depression to five causes. First was the bad distribution of income: a lot of wealth was put in the hands of a few, who used the wealth to speculate. Corporate profits rebounded significantly in the 1920s, but wages increased relatively modestly. Second was bad corporate structure: the rise of investment trusts (“a profound source of weakness”) encouraged rent-seeking on the part of promoters. Galbraith wryly refers to the “bezzel,” the value appropriated by promoters from credulous investors. Third was a bad banking structure: too many small, undercapitalized banks. Fourth was the dubious state of foreign debt balances. The overhang of war debts and reparation payments was a massive drag on European economies and led to the collapse of the gold standard. Fifth was the poor state of economic intelligence—not only did decision-makers not have much clarity about the economic trends going into the Depression, but also their economic orthodoxy led to actions by the Fed and Treasury that were counterproductive to recovery. For Galbraith, the story of descent into Depression is an economic story, framed largely around rent-seeking and the flaws in the capitalist system.

Herbert Hoover marshals considerable evidence to tell what is, essentially, a political story. He recounts the Depression as consisting of several phases. At each phase, public policy decisions are made that create a “degenerating vicious cycle.” (Page 87.) The Depression did not start in the U.S. The “storm center” was in Europe and originated in the Versailles Treaty of 1919. Post-war optimism in America created “new era thinking.” And a stimulative Fed policy created a stock market bubble. All of this happened “before I entered office.” After the Crash occurred, “The record will show that we went into action within ten days and were steadily organizing each week and month thereafter to meet changing tides.” (Page 31.) In 1930, Hoover organized a voluntary commitment by business leaders to maintain wages and employment. This proved to be unsustainable in the face of continued decline. From April to July 1931, Hoover focused on “indirect relief” to provide jobs, support wages and prices, limit immigration. He also sought appropriations for public works. In 1931, it became evident that European nations would not be able to meet scheduled payments of debts and reparations. Hoover declared a moratorium on payments. Still European government engaged in what Hoover called “kiting” of payments among themselves. Then Britain collapsed and took itself off the gold standard, which damaged business confidence further. In 1932 Hoover sought Congressional support for an 18-point legislative program of reconstruction finance, land banks, home loan banks all of which encountered political resistance, “a rottenness worse than I had anticipated.” (Page 128.) Hoover couldn’t understand the failure of Congress to support his program. He described one Senator as “a curiously perverse person with alternating streaks of generosity and hatred…a profound reactionary.” (page 113.) In the months between FDR’s election in November, 1932 ,and FDR’s inauguration in March, 1933, the President-elect declined to cooperate with Hoover on a recovery program. And so on. Hoover’s memoir reads like a classic tragedy: good man brought low by forces beyond his ken.

David Kennedy’s history of the Great Depression expresses some sympathy for the “ordeal of Herbert Hoover.” But Kennedy seems interested in giving a history that is more than economics or politics—he features plenty of both but adds a somewhat more social/psychological perspective. Kennedy tells us about Hoover’s Quaker upbringing and of his belief in the efficacy of volunteerism instead of state intervention. Hoover was an internationalist, but caved in to the populist/nationalist sentiments of Congress when he signed the infamous Smoot-Hawley Tariff. The nadir of Hoover’s efforts was not measured in economic or political terms but in the expulsion of a social protest movement, the “Bonus Army,” from Washington D.C. in July, 1932—it was, said Kennedy, “the lowest ebb of Hoover’s political fortunes.” (Page 92.) Kennedy suggests that leadership mattered in the deepening Depression. Kennedy’s profiles of the major participants lend the view that the awful downward spiral was not dictated solely by large social forces. Rather, the predilections of key players also mattered immensely. For instance, of Hoover, he writes,

“Herbert Hoover forged his policies in the tidy, efficient smithy of his own highly disciplined mind. Once he had cast them in final form, he could be obstinate. Especially in his last months in the White House, he had grown downright churlish with those who dared to question him. Roosevelt’s mind, by contrast, was a spacious cluttered warehouse, a teeming curiosity shop continuously restocked with randomly acquired intellectual oddments. He was open to all number and manner of impressions, facts, theories, nostrums, and personalities.” (Page 113.)

In responding to the Depression, Hoover clung to what was familiar (like the volunteer effort in fighting famine in Europe) rather than inventing a new response appropriate to the circumstances of 1929-1933. In short, Kennedy’s history affords the third narrative, about attributes of leadership.

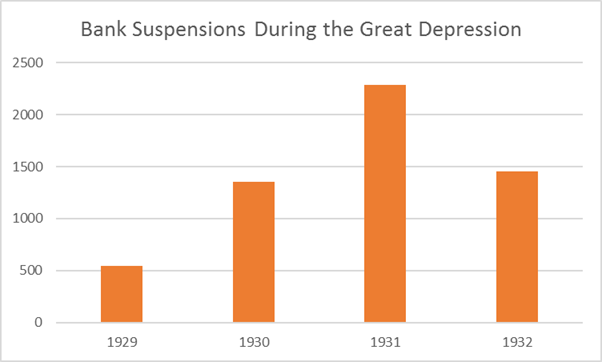

Largely missing from these narratives of 1929-1933 is the dramatic collapse of the U.S. banking system during those years. Overpopulated with competitors (numbering 26,213 national, state, Building and Loan organizations, savings banks, private banks, and other at June, 1928), ((1928 Report of the Comptroller of the Currency, https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/files/docs/publications/comp/1920s/compcurr_1928.pdf)) unprepared, undercapitalized, and under-regulated, the industry suffered a dramatic contraction. (In 2016, the U.S. has 5,141 banks.) ((Source: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/USNUM)) Throughout the 1920s, the failure rate of banks was high, averaging 600 per year and concentrated especially among small unit banks in agricultural areas. As Figure 4 shows, the annual failure rate spiked during the downturn.

Figure 4: Bank Suspensions During the Great Depression

Source: Author’s analysis drawing on data from Wicker Banking Panics of the Great Depression (1996).

Thus, during the first stage of the Great Depression, the banking industry contracted by about 20% in the number of players. Lending declined as bankers sought the high ground of exposure to only the most creditworthy debtors. Individuals hoarded their savings. In the absence of deposit insurance, a bank failure would mean the loss of some of the depositor’s savings. The extent of actual losses due to suspensions was probably sizable, but dwarfed in impact by the loss in confidence in the business economy and the increase in fear.

Synthesis: A Pernicious Self-Reinforcing Cycle

The three books for this session help to convey the plurality of narratives for the awful descent into the Great Depression. The stock market Crash of 1929 occurred shortly after the onset of recession and cannot be said to have caused the Great Depression. But it probably helped to accelerate and deepen the recession through the “wealth effect” and loss of confidence. Maladroit responses by government leaders also deepened the Depression. The Smoot-Hawley Tariff probably had a smallish impact on the U.S. economy but imposed a major chill on diplomatic relations that obstructed coordinated response to the Depression. Economic historians point to lurches in monetary and fiscal policy that created a drag on recovery—orthodox economic thinking of the day embraced balanced budgets and the “real bills doctrine” in Fed lending into the financial system. The international economic malaise weakened what should have been a robust economy. Technological change in agriculture and manufacturing imposed a deflationary bias on the economy. And finally, attributes of leaders (including obstinacy, pessimism, slow reaction, and weak communication skills) hampered the mobilization of collective action.

Elements of this saga seemed to reinforce each other, creating a feedback loop that accelerated and deepened the downturn. Tight Fed policy, recession, stock market crash, political in-fighting, a distressed banking system, and reactive leadership made a toxic stew. In coming sessions, we will consider what it takes to break a pernicious self-reinforcing cycle.