An important lesson of the presidency of George H.W. Bush is the importance of an identity to the success of a leader. An identity refers not only to substance (as in an ideology) but also style (as in how one gets things done.) Identity emerges as a crucial issue in a reading of Bush’s memoir, All the best, G. Bush: My Life in Letters and Other Writings and two biographies of him. This is one of the oddest presidential memoirs to be found—mostly tidbits of diary and correspondence in chronological sequence, but not a narrative argument. What did President Bush intend for us to take from this?

Eleven students and I are reading our way through the autobiographies and biographies of the post-Watergate U.S. Presidents. ((After our first seminar meeting, I distilled our discussion into five components for understanding a President: circumstances, character, choices, execution, and outcomes. And I argued that these components are interdependent, making it challenging to understand causality: when we encounter a successful or failed President, the temptation is to point to simple explanations. Our study of the Presidents this year suggests that success or failure is usually a more complicated story.)) George H.W. Bush brought to the White House a resume of considerable experience: decorated veteran of World War II, successful entrepreneur, Congressman, Chairman of the Republican National Committee, Ambassador to the U.N., Chief of the U.S. Liaison Office to China, Director of Central Intelligence, and Vice President. As President, Bush invaded Panama and arrested the military dictator, Manuel Noriega, for drug-dealing. Bush marshalled some 80 nations in wresting Kuwait away from Saddam Hussein in 1991. And he adroitly managed relations with China in the wake of the massacre at Tiananmen Square in 1989 and with USSR at the fall of the Berlin Wall and breakup of the Soviet Union. Yet he failed to gain re-election in 1992, and joined the club of nine other Presidents who sought a second term and where defeated. To most of these ten Presidents, history has not been kind. Judged in the longer view, historians rank him at around #22 among all 44 Presidents. There is no legacy for George H.W. Bush of the kind that graces the memory of his predecessor, Reagan. Five considerations help to explain why.

Circumstances. George H.W. Bush (hereafter, “Bush41,” which helps to distinguish the 41st President from his son, the 43rd President, “Bush43”) presided over massive changes in geopolitical history. The dissolution of the USSR and reunification of Germany narrowly escaped a crackdown and coup attempt by Soviet hardliners. The massacre at Tiananmen Square threatened to derail the rapprochement with China. The invasion of Kuwait by Iraq in 1990 and the massing of Iraq’s troops on the border with Saudi Arabia threatened stability in the Middle East. For his careful handling of these temblors, historians grant him good to very good marks.

Bush41 also inherited the legacy of the Reagan Revolution that had achieved tax cuts without offsetting budget cuts. The S&L Crisis and onset of a recession in 1990 threatened to deliver record-setting government deficits. In reaction, the Republican coalition fractured, and generated two populist challengers on the right, Ross Perot and Pat Buchanan.

Character. Much is made of Bush41’s privileged background. He was the son of a successful banker who was elected U.S. Senator. His mother instilled strong values of loyalty, respect, service, and the “obligation to lead” (page 391). The first eight pages of his memoir are a glossary of names that reveal a great deal about what Bush41 valued: “close,” “closest,” “friend,” “trusted,” describe almost half of them. Other themes that figure heavily in describing those he values are loyalty, support, intelligence, integrity, honesty and respect. More than any other presidential memoir, Bush41 displays a strong relational bent. His memoir is riddled with references to “faith, family, friends” (page 391), “family is key” (page 388). In describing his reaction to the loss of the presidency in 1992, Bush41 wrote,

“Hard to describe the emotions of something like this…But it’s hurt, hurt, hurt and I guess it’s the pride too…be strong, be kind, be generous of spirit. Be understanding and let people know how grateful you are. Don’t get even…finish with a smile and some gusto and do what’s right and finish strong.” (Page 572.)

Choices. Belying the image of a pampered young man from a privileged background, Bush41 repeatedly made choices that took him out of stable and secure territory. In 1941, he graduated from Andover and enlisted in the Navy to become an aviator—this, despite a graduation speech by Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson that urged his classmates to go to college. It was dangerous service by any stretch of the imagination and prove so when he was shot down and rescued in the Pacific Ocean. After the war, he graduated from Yale phi beta kappa, in a day when the social norm was for Yalies to get a “gentlemen’s ‘C’”. Then he left the comforts of Connecticut to go to Texas, to sell oil-drilling equipment. And then, offered a position with the prestigious banking firm of Brown Brothers, Harriman in New York, he declined the offer and instead started his own oil exploration firm. He helped to build the Republican Party in Texas when being a Republican wasn’t politically acceptable. He accepted political appointments that advisers said would mark the dead-end of his career (heading the legation in China in 1974, Director of the CIA in 1975). This is the profile of an ambitious risk-taker, not a silk-stocking namby-pamby.

Judging from declarations and choices that Bush41 made, he positioned himself as a liberal Republican—notwithstanding his support of Barry Goldwater in 1964 and his acceptance of the Vice Presidency under Ronald Reagan in 1980. He supported de-segregation in Texas in the 1960s, gay rights and family planning. He purged John Birchers from the Texas Republican Party. Clearly an internationalist in his reliance on diplomacy and treaties, he was willing to intervene where America’s strike force and moral authority would achieve outcomes for the global good (e.g., Kuwait and Panama.) He believed in less government intervention in everyday life, and more volunteerism and charity.

In coaching his speechwriter, Peggy Noonan, about drafting his acceptance speech at the Republican Convention in 1988, he wrote,

“Vision. On the domestic side jobs, but jobs in an America that is free of drugs, that is literate, that is tolerant. On the foreign policy side—peace, but peace in a world that offers more freedom, more democracy to the people of the world.” (Page 351.) “What drives me comforts me: family, faith, friends. We have a special obligation to lead. We must not forget our responsibility…We owe it to the free nations of the world to lead, to stay strong, to care…strive for a truly bipartisan foreign policy—and never give up on liberty.” (Page 391.)

Noonan fleshed out this brief advice into a broad summation of Bush41’s worldview: a tendency to see life as a series of missions; a “kinder, gentler nation;” gun rights; the death penalty; first rate education; drug free America; inclusion of the disabled; world peace through strength; celebration of the individual; in all, an “enduring dream and a thousand points of light,” “a message of hope and growth for every American to every American” (watch here). And in his inaugural address of 1989 (watch here), Bush41 said that he took as his guide “the hope of a saint: In crucial things, unity; in important things, diversity; in all things, generosity.”

But viewed from the span of 28 years, these addresses look like boilerplate, mainstream Republican orthodoxy. What, exactly, would Bush41 add to the political stew in Washington? In what ways would he actually lead? The acceptance speech and inaugural address presaged Bush41’s signal problem during his presidency, “the vision thing.” People found it difficult to know what he stood for. Timothy Naftali wrote that when Bush arrived as a new Congressman in January 1967,

“Bush’s thinking evolved once he reached Washington. He had few, if any settled policy ideas. What he had were tendencies: Bush disliked extremism of any kind; he preferred to seek solutions outside of the federal government; he believed in a strong defense and in strong support for the U.S. military; he preferred spending cuts over higher taxes; he opposed segregation and racial discrimination, but he was uncomfortable in having Washington mandate good behavior. Despite his conservative temperament, Bush proved to be pragmatic and emotional. Quickly dropping any pretense to being a Texas conservative, he allied himself with moderate civic Republicans, who believed in the goals of the Great Society and the war in Vietnam but wanted both to be managed more efficiently.” (Pages 16-17.)

As one reads or listens to Bush’s speeches in 1992, he seemed continually to be evolving. Bush contrasted starkly with his predecessor, Reagan, who had framed a series of stirring visions for voters and who had articulated a strong ideology. Whether Bush41 could hold together the coalition of moderate and conservative Republicans would depend on his execution of the vague vision.

Execution. The memoir of Bush41 highlights several attributes about the way he executed his responsibilities:

· He listened. Bush41 wrote, “Leadership is listening then acting. Leadership means respect for the other person’s point of view, weighing it, then driven by one’s own convictions, acting according to those convictions. If you can’t listen, you can’t lead.” (Page 351.) As a relational leader, listening is paramount. The inclination to lead by listening proved to be of paramount importance in navigating through the international crises Bush confronted.

· He took measured steps in conflict. At the massacre in Tiananmen Square in Beijing in May, 1989, Bush43 wrote, “Dad struck a careful balance…He denounced the Chinese government’s use of force and imposed limited economic sanctions…Dad drew on his personal connections and wrote a private letter to Deng Xiaoping…whom he addressed as “Dear Friend.” (Page 192.) Bush43 summarized his father’s decision to liberate Kuwait: “I admired the way Dad handled the situation. He had taken his time. He had explored all options…He had rallied the world and Congress to his cause.” (Page 199.)

· He played the long game. Bush41’s memoir suggests that he foresaw the economic collapse of the USSR as early as the mid-1980s, but was patient. To try to hasten change would risk arousing hardliners who might respond in force—as they ultimately tried to do in a coup d’etat against Gorbachev in 1991. In 1990, Bush delayed recognition of the breakaway Baltic republics to temper the anxieties of Russian hardliners and gain time for a united Germany to be included in NATO. Timothy Naftali wrote, “Thus, George H.W. Bush for a moment, at least became a great President…risked his international prestige [and negotiated the bipartisan budget] in each case Bush sacrificed short-term political gain for what he considered the national interest.” (Page 98.)

· He dealt in relationships, not transactions. In addition to addressing Deng on a friend-to-friend basis, he developed a similar rapport with Gorbachev. Bush43 wrote,

“Dad’s strategy was to develop his friendship with Gorbachev while privately urging him to allow the Soviet Union to unwind peacefully. The strategy paid off in early 1991 when Gorbachev agreed to allow a free election for President of the Russian Federation…He believed that encouraging Gorbachev—not provoke the Soviet hardliners—was the best way to avoid a crackdown…I don’t believe Gorbachev could have endured without a partner in the United States.” (Pages 212 and 214.)

· He played by the rules. Bush 41 defended his decision not to pursue Saddam Hussein into Iraq, and instead respected the strict limitations of the U.N. mandate to liberate Kuwait: “I still do not regret my decision to end the war when we did. I do not believe in what I call “mission creep.”” (Page 514.)

· In victory, he did not gloat. Humility is one of the dominant sentiments in Bush41’s memoir. His son echoed this attribute in describing the moment that the Berlin Wall fell in November, 1989:

“Dad faced enormous pressure to celebrate…Dad refused to give in to the pressure. All his life, George Bush had been a humble man. He wasn’t trying to score points for himself; he only cared about the results…Freedom had a better chance to succeed in Central and Eastern Europe if he did not provoke the Soviets to intervene in the budding revolutions. “I’m not going to dance on the wall,” he said.” (Page 195.)

In other respects, Bush41 may have listened, but did not hear so well. Here he is, recounting his response to White House aides who were worried by a possible challenge from Ross Perot in 1992:

“I told them that in three months, he will not be a worry anymore. Perot will be defined, seen as a weirdo…Their view is that the move for change is so much outside that outsiders are in and insiders are out; and that Perot can take his money and parlay himself into victory or into a serious threat. We need to be very wary of this, but time will tell…[On the same page in a footnote, he declared,] They were right and I was wrong. In the final analysis, Perot cost me the election.” (Page 555.)

But was the problem only Perot? Bush41 was challenged by Pat Buchanan as well. Both challengers came from the populist right-wing of the electorate. At the core of their challenge was Bush’s failure to shrink government spending at the moment of budget crisis in 1990 and to renege on his pledge at the 1988 nominating convention, “Read my lips: no new taxes.” “The budget agreement was a disaster,” wrote Bush43. It fractured the Republican Party, obscured other domestic accomplishments and reflected a poor job of communicating and defending the agreement. Timothy Naftali wrote,

“Whether due to naivete, renewed self-confidence, or arrogance, Bush assumed that his personal charm, his honesty, and his sense of a mutual interest in good government would suppress his opponents’ interest in seeing him hurt politically…Bush became an object of increasing public scorn…made matters worse by reacting ineptly to his image problem.” (Pages 99 and 140.)

Lyn Nofziger later commented, “He was an ineffective one-term President. [He] walked away from the Reagan legacy and tried to create his own—and failed at that.” (In Naftali, page 161.)

Outcomes. The paradox is that close observers like Nofziger deem Bush41 a “failed President,” despite the many accomplishments on Bush’s watch. The wins would include the end of the Cold War, the successful expulsion of Iraq from Kuwait, the arrest of Manuel Noriega, the unification of Germany, the American Disabilities Act, the Civil Rights Act of 1991, the Clean Air Act Amendment of 1992, the Points of Light Project, and the appointment of two Supreme Court Justices. Not shabby for a one-term President.

On the other side of the ledger, Bush41 lost to Bill Clinton and prompted moderate Republicans to flee the field. Clinton won with 43% of the popular vote and 370 electoral votes; Bush received 38% of the popular vote and 168 electoral votes; Perot took 19% of the votes. The right-wing populists gained momentum as the heirs to the Reagan Revolution and under the leadership of Newt Gingrich wrested leadership of the House of Representatives in 1994. Essentially, this faction echoed the ideology of Pat Buchanan and Ross Perot: cut the deficits, balance the budget, protect American industry, oppose foreign wars, and generally oppose the establishment and longstanding incumbents.

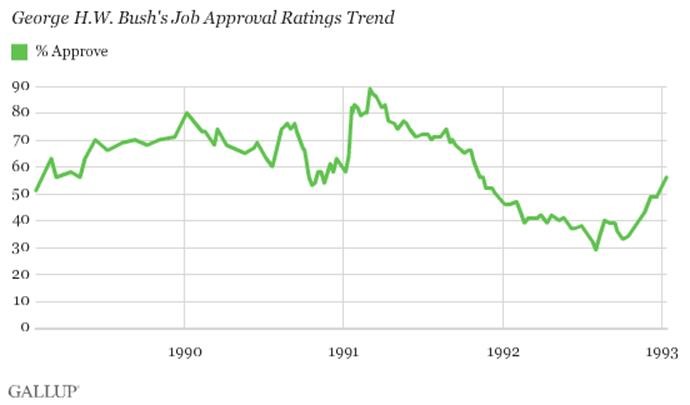

Epitomizing the incredible reversal in fortunes for Bush41 was his approval rating. The following graph reveals that during Bush’s first two years, he was popular, if not even highly approved. His rating peaked at 89% (Feb. 28, 1991) at the end of the Gulf War and hit bottom at 29% 18 months later, on July 31, 1992, at the outset of his campaign for re-election. By the date of Clinton’s inauguration, Bush’s approval rating was back in positive territory.

Source: Gallup Historical Presidential Job Approval Statistics http://www.gallup.com/poll/116677/Presidential-Approval-Ratings-Gallup-Historical-Statistics-Trends.aspx

In October, 1987, Newsweek magazine published a devastating cover-story article on Bush, titled, “Bush Battles the ‘Wimp Factor’”.

“Bush suffers from a potentially crippling handicap — a perception that he isn’t strong enough or tough enough for the challenges of the Oval Office. That he is, in a single mean word, a wimp. ‘A problem’: The epithet has made its way from the high-school locker room into everyday jargon and stuck like graffiti on Bush. What’s come to be known as the vice president’s “wimp factor” is a problem, concedes Bush pollster Robert Teeter, “because it is written and talked about so much.”… “Fairly or unfairly, voters have a deep-rooted perception of him as a guy who takes direction, who’s not a leader,” says Democratic pollster Peter Hart… (Literally. Last week the “Doonesbury” strip portrayed voters matter-of-factly describing Bush as a wimp.)…Why, then, is he so cruelly mocked? The reasons are both stylistic and substantive. Television, the medium that makes Ronald Reagan larger than life, diminishes George Bush. He does not project self-confidence, wit or warmth to television viewers. He comes across instead to many of them as stiff or silly… Beneath such surface qualms lie deeper doubts. What does Bush really stand for? His two decades in government have produced an impressive resume — congressman, U.N. ambassador, Republican Party chief, China envoy, CIA director, vice president. But his imprint on all those jobs is indistinct, even his friends admit, and he seems to have avoided the great social and political controversies of a quarter century. In short, Bush is by and large a politician without a political identity.”

Biographer Timothy Naftali wrote:

“In the nearly quarter century since his first run for federal office, Bush had yet to fashion for himself a political program. He had coexisted with three major Republican leaders, Goldwater, Nixon, and Reagan, each of whom saw the world differently, and Bush had served each of them loyally. Many observers considered Bush’s political adaptability a sign of weakness…No one questioned the physical courage…It was his political courage that was in question.” (Page 51.)

The memoir of Bush41 recounted the wimp episode with emotion.

“Handlers want me to be tough now, pick a fight with somebody…the ‘wimp’ cover, and then everybody reacts—pick a fight—be tough—stand for something controversial, etc. etc. Maybe they’re right. But this is a hell of a time in life to start being something I’m not. Let’s just hope the inner strength, conviction, and hopefully, honor can come through.” (Page 369.)

Reflections for leaders

What explains the unusual format of Bush’s memoir? As with most memoirists, he wanted to explain himself, not just what he did, but who he was. This was his last, best shot at establishing his identity. He wrote,

“When I left office and returned to Texas in January, 1993, several friends suggested I write a memoir. “Be sure the historians get it right,” seemed to be one common theme. Another: “The press never really understood your heartbeat—you owe it to yourself to help people figure out who you really are.” I was unpersuaded…Lisa Drew suggested that what was missing is a personal book, a book giving deeper insight into what my own heartbeat is, what my values are, what has motivated me in life…It’s all about heartbeat.” (Pages 21-22.)

George H.W. Bush offers a useful basis for thinking about the identity of a leader. The undercurrent of Bush41’s career was the lingering question, “Who is George Bush?” The simple answer is that a mushy vision and political adaptability render the answer, “I don’t know.” But we can do better than that. The five elements suggest at least two dimensions along which we could size up a leader.

1. Relational versus transactional. What distinguished Bush41 from Reagan, Carter, or Ford was his candor about his intense network of relationships, based on family, friends, and faith. His memoir is unlike any other presidential autobiography that one can find: rather less about policy and politics and much more about relationships. One of the most important ways to parse leadership styles is the extent to which it is transactional versus relational. And I hasten to add that no one who is elected to the White House is totally one or the other; but it is very useful to consider tendencies.

The ultimate transactional leader is the piece-rate bargainer: everything about an exchange is measured in tangible “gives” and “gets”—think of the deal-making of Lyndon Baines Johnson or the “government by deal” implied by the early actions of Donald J. Trump. With such a leader, extra effort or output wins immediate reward; similarly, retribution for failing to meet goals is quick and Darwinian (think of Trump’s show, The Apprentice, and “you’re fired!”) The transactional leader may promote competition among followers. There is no reward for assisting a colleague—it just takes time that you could be using to stay ahead. Boiler-room sales operations work like this; in more elegant surroundings you will find that some professional services firms and financial organizations offer essentially the same environment. To get ahead in such organizations, you must stay ahead of the average of your colleagues. Never admit weakness. And never hesitate to ask for a better deal. “If you don’t ask, you don’t get” might be the cultural motto. The transactional leader can be stressful to work for; the employment demands are clear and the consequences immediate.

The relational leader reflects a more complicated social contract. What matters is the long-term relationship, not just the near-term tradeoff. Surely, as the relationship prospers, the individual tends to prosper. But the contract goes well beyond piece-rate and may include expectations for a contribution to the success of the team, contribution over time rather than in the moment, and contribution to quality rather than simply volume. As the term, “relational,” implies, the glue for such leaders is not the individual transaction, but rather the strength of the network. Relational leaders can impose big burdens on their employees, who are asked to live up to a strong internal culture; the employment demands are probably ambiguous and open-ended.

2. Ideological versus pragmatic. The ideologue is dogmatic and uncompromising, adhering to principles and ideals, a focused partisan. The principles or ideals derive from values: economic, political, social, or religious. For the ideologue, justifying a principled stand often entails an emotional appeal to values. In the public mind, Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher were ideologically-motivated leaders. Jimmy Carter pursued the Egyptian-Israeli Peace Treaty out of religious conviction. To follow an ideological leader entails demonstrating loyalty by espousing the right ideas—one needs to drink the Kool-Aid, and do it in a way consistent with the ideology.

The pragmatist, on the other hand is focused especially on the means to achieve some goals. “To make an omelet, you must break a few eggs,” as the French say. Ideas are valuable if they are practically useful. Lyndon Johnson was famous for back-room deal-making in pursuit of his Great Society programs. Richard Nixon supposedly declared, “We’re all Keynesians now” and supported greater state intervention in markets in the midst of a financial crisis. To follow a pragmatist leader entails achieving the right outcomes in a way that is efficient and effective. It is not what you say, but what you do, that counts.

3. Morally courageous versus passive. History has dealt harshly with Presidents who declined to confront and grapple with the supreme challenges of their day. James Buchanan (1856-1860) allowed “bleeding Kansas” to bleed and did virtually nothing to stop the momentum toward civil war. Andrew Johnson (1865-1868) declined to implement policies to integrate liberated slaves into society. “Moral courage,” the willingness to fight or confront problems, is the premier attribute of a leader, according to the memoir by Ulysses S. Grant (1868-1876). And Theodore Roosevelt wrote:

“It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.” (Speech at the Sorbonne, April 23, 1910.)

Our readings about George H.W. Bush suggest that he tended to be a relational pragmatist—and he showed remarkable moral courage at important moments in his career. Ironically, his adaptability, and his ability to engage with virtually everyone, and his inarticulate summation of what he stood for contributed to his defeat. A sense of identity makes it easier for followers to know what the leader stands for. It will be a topic of enduring discussion in our seminar whether the leader chooses the identity, or the times confer the identity on the leader. The answer resides in the interdependence among circumstances, character, choices, execution, and outcomes.

Works Referenced

George W. Bush, 41: A Portrait of My Father, New York: Crown Publishers, 2014.

Timothy Naftali, George H.W. Bush, American Presidents Series, Times Books, 2007.