Read here.)

“Let’s make America great again.” – Reagan campaign poster, 1980.

“It’s morning again in America. Today more men and women will go to work than ever before in our country’s history. With interest rates at about half the record highs of 1980, nearly 2,000 families today will buy new homes, more than at any time in the past four years. This afternoon 6,500 young men and women will be married, and with inflation at less than half of what it was just four years ago, they can look forward with confidence to the future. It’s morning again in America, and under the leadership of President Reagan, our country is prouder and stronger and better. Why would we ever want to return to where we were less than four short years ago?” — Reagan re-election campaign, 1984 (Listen here.)

Reagan communicated very effectively. The political power of the word spoken well may be the prime lesson of Reagan’s presidency. Of course, his presidency stands out for other attributes as well: his conservative ideology, his muscular foreign policy, and for a “revolution” in the relationship between government and governed. As an aspirant to the White House, he was disparaged as a Hollywood actor. Yet he was elected to two terms as Governor of California (one of the largest states in the nation) and in 1980 was elected President by a “landslide,” gaining 489 electoral votes. ((Reagan’s landslide accrued only 50.7% of the popular vote, less than other popular presidents. The American Constitution entails a weighted voting system that favors less-populous states.)) He was the first President in 28 years to serve two full terms. ((Dwight Eisenhower’s second term ended in 1960; Reagan’s ended in 1988.)) Judged in the longer view, historians have been kind to him, ranking him recently at #9 among 43 Presidents. And the “Reagan Revolution” appears to have had lasting impact. It would seem that Reagan’s presidency holds some lessons for students of leadership.

This post continues my reflections stemming from the year-long seminar that I’m leading on the “Leadership Lessons of the Post-Watergate Presidents.” In that seminar, we’re reading the memoirs and biographies of these Presidents. In my first course post, about Gerald Ford, I offered a model for thinking about the Presidents that focuses attention on five elements: circumstances, character, choices, execution, and outcomes. Reagan’s profile on these elements is distinctive, especially in comparison with his two immediate predecessors, Ford and Carter:

1. Circumstances: The Watergate scandal and associated revelations of 1972-1974, Arab oil embargo of 1974, America’s ignominious exit from Vietnam in 1975, recession of 1974-75, “stagflation” of 1978-79, and the Iran Hostage Crisis of 1979-80 put the electorate in an ugly mood for the 1980 presidential election. The incumbent powers in national politics (left/liberal Democrats and centrist Republicans) seemed played out. Conservative Republicans had been building momentum since Reagan’s first election as Governor of California in 1967. Reagan entered office with a crisis in the public sector (in contrast to Franklin D. Roosevelt, who entered office with a crisis in the private sector). Reagan wanted to be identified with a resurgence, a recovery of domestic conditions, with “Morning in America.” Reagan’s overarching goals during his presidency were to reduce the scope of government and end the Cold War.

2. Character: Almost a third of Reagan’s memoir, An American Life, is devoted to his upbringing and preparation as a politician. Born into a humble socio-economic setting, son of an alcoholic father and of a mother of strong character, Reagan made his own way. Indeed, much of the memoir is the portrayal of Reagan as everyman, the iconic American, who, through hard work, ingenuity, faith, optimism, and fair dealing, succeeded in family, career, and service to others. Pivotal character-building experiences for Reagan included learning to broadcast sports events (helping listeners “see” a game through Reagan’s words), expelling communists from the Screen Actors Guild of which Reagan was president, and speaking to employees of General Electric (a graduate school in political science, he said.) Reagan wrote, “During eight years of travels for General Electric and during the campaign for governor, I’d gotten a good idea of what was on the minds of people. They wanted their government to be fair, not waste their money, and intrude as little as possible in their lives.” (Page 170.)

3. Choices: One chooses one’s ideology. By 1980, Reagan had views that were distinctive, fresh, and appealing to the electorate. “Conservative” was a label tarnished by memory of such people as Herbert Hoover (the “Great Engineer” who failed to avert the Great Depression and then railed against the New Deal), Joseph McCarthy (demagogic Senator and communist-chaser), George Wallace (racist), and the John Birch Society (right-wing conspiracy theorists). The identity of such conservatives was to be against trends in society. Reagan on the other hand seemed to frame an ideology for values that had broad appeal: freedom (from an intrusive government), light taxation, law and order, right to work, and capitalism. Reagan wrote, “The classic ‘liberal” believed individuals should be masters of their own destiny and the least government is the best government; these are precepts of freedom and self-reliance that are at the root of the American way and the American spirit.” (Page 135.) Reagan believed in small government and quoted James Madison (“there are more instances of the abridgement of the freedom of the people by gradual and silent encroachment of those in power than by violent and sudden usurpations”) and Thomas Jefferson (“What has destroyed liberty and the rights of men in every government that has ever existed under the sun? The generalizing and concentrating of all cares and powers into one body.”) (Page 196.) And Reagan was a staunch defender of capitalism and critic of socialism and communism. He broke a diplomatic taboo by labeling the Soviet Union the “Evil Empire” and wrote, “The great dynamic success of capitalism had given us a powerful weapon in our battle against Communism—money. The Russians could never win the arms race; we could outspend them forever. Moreover, incentives inherent in the capitalist system had given us an industrial base that meant we had the capacity to maintain a technological edge over them forever.” (Page 267.) Reagan believed in American exceptionalism. In one speech, Reagan said, “I, in my own mind, have thought of America as a place in the divine scheme of things that was set aside as a promised land…this land of ours is the last best hope of man on earth.” (Weisberg, pages 30-31.)

4. Execution: Four attributes stand out regarding Reagan’s leadership style: excellent communication, determination, and delegation.

a. Communication: Reagan portrayed a charm and approachability that established warm rapport with an audience. He told stories and jokes with ease (listen here and here.) Reagan’s memoir conveys his rules for speaking, “I prefer short sentences; don’t use a word with two syllables if a one-syllable word will do; and if you can, use an example. An example is better than a sermon…I usually start with a joke or story to catch the audience’s attention; then I tell them what I am going to tell them, I tell them, and then I tell them what I just told them.” (Pages 246-7.) For more insight into the possible impact of the spoken word, you should listen to Reagan’s two inaugural addresses (1981 and 1985), his “Evil Empire” speech in 1983 (here), and the speech in Berlin in 1987 (“Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall.”) (here).

b. Determination: Perhaps reflecting his strong ideology, Reagan emerges not as the Washington-style pragmatist (like Ford, Bush41, or Clinton) but as a friendly but firm advocate for his principles. The Reagan administration was unable to reduce federal spending because he had no majority in the House of Representatives, which originates spending bills—“This was one of my biggest disappointments,” he wrote. (Page 335.) But Reagan’s determination may be best reflected in his dealings with the Soviet Union and his aspiration to eliminate nuclear arms. Reagan wrote, “As the foundation of my foreign policy, I decided we had to send as powerful a message as we could to the Russians that we weren’t going to stand by anymore while they armed and financed terrorists and subverted democratic governments. Our policy was to be one based on strength and realism. I wanted peace through strength, not peace through a piece of paper.” (Page 267.) The Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) relied on unproven speculative technology. But SDI proved to be an important bargaining chip. Even though many American experts doubted the effectiveness of the technology, Reagan quipped that as long as Gorbachev thought it would work, Reagan was going to pursue it. His strategy paid off with a breakthrough accord to reduce nuclear arms.

c. Delegation: Reagan was a champion delegator—in strong contrast to Carter, who might be deemed a micromanager. But he did not monitor his delegates very carefully. He trusted his appointees to implement his directives, which ultimately got Reagan into trouble in the Iran-Contra Affair that tarnished his second term. Almost a quarter of Reagan’s memoir is preoccupied with the scandal. In essence, a scheme to trade arms for hostages violated Reagan’s ban on negotiating with terrorists. And a subterfuge in marking-up the sale price would provide financial support to anti-Sandinista guerillas in Nicaragua—this violated laws prohibiting such support. Congressional investigations and the Tower Commission, which studied the affair, strongly criticized Reagan for inattention and lack of supervision of subordinates. On March 4, 1987, Reagan addressed the nation on TV and took full responsibility for the affair, though in his memoir, Reagan admitted, “On any given day, I was sent dozens of documents to read, and saw an average of eighty people I set the policy, but I turned over the day-to-day details to the specialists. Amid all the things that went on, I frankly have had trouble remembering many specifics of the day-to-day events and meetings of that period, at least in the degree of detail that subsequent interest in the events has demanded.” (Page 516.) Twelve subordinates were indicted for violation of the law. Oliver North and others have asserted that Reagan knew what was going on. Some observers think Reagan was lucky not to be impeached. Yet as the “Teflon President,” Reagan emerged in January 1989 with a 64% approval rating, the highest end-of-term approbation for any President up to that time.

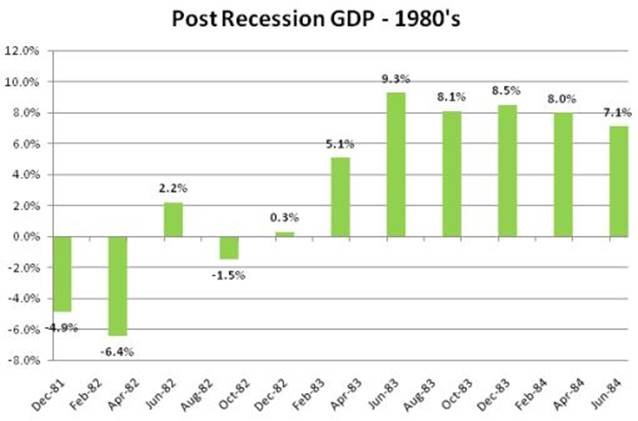

5. Outcomes: In his 1980 campaign, Reagan asserted that America was losing faith in itself. By 1988, America seemed to have rediscovered its mojo. Aside from an assertive foreign policy that stood up to Soviet expansionism, the American economy recovered.

Many political scientists note that the approval ratings of Presidents are highly sensitive to economic growth and employment. No doubt, Reagan benefited from the buoyant economy. The booming economy was due in part to the dramatic Reagan tax cut in his first term, which owing to the inability to cut spending, contributed to the debt problem the country faces today.

From the long view of 28 years, the legislative, diplomatic, and administrative achievements of the Reagan administration seem dwarfed by the larger and more inchoate legacy of the “Reagan Revolution.” Biographer Jacob Weisberg wrote, “What Reagan did change was the public’s attitude toward government, for better or worse. Reagan followed a string of foreshortened presidencies: those of Johnson, Nixon, Ford, and Carter. Many political scientists came to believe that the job had become impossible: the executive branch was too vast and complex for any one person to manage. Reagan’s popularity and accomplishments restored the idea that someone could be successful in the job.” (Pages 152-3.)

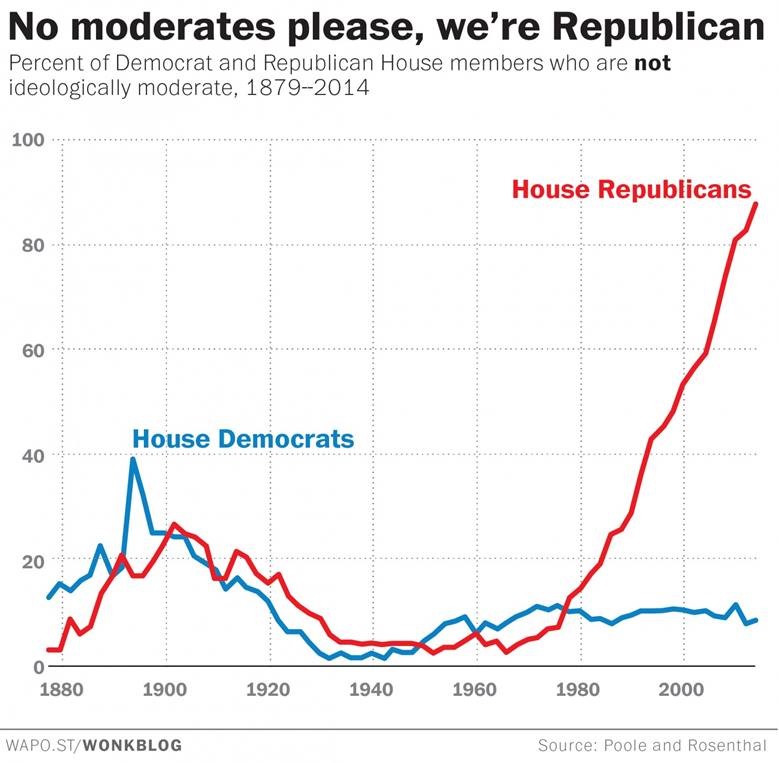

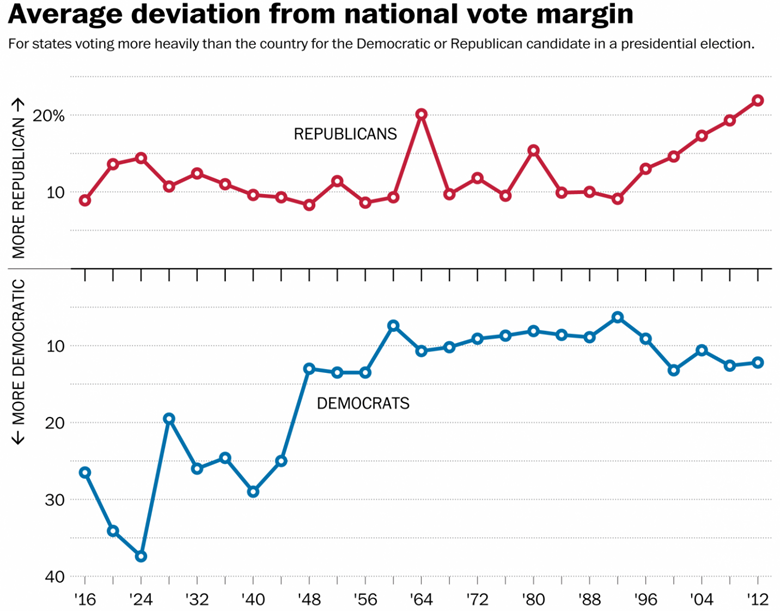

Judging from the primary campaigns and debates in 2016, the Republican Party platform reflects the long legacy of Reagan. ((In some material ways, the leadership of Donald Trump departs of the Reagan model, which calls into some question its sustainability.)) Stephen Skowronek, a political scientist at Yale, has offered a theory that presidential leadership and ideology cycle through time and that the liberal ideology of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal ran out of public support with the Carter administration and that the election of Reagan marked a new cycle in “presidential time.” Skowronek wrote, “[Ronald Reagan] came to power in circumstances that recalled the great reconstructive crusades of the past. An economic crisis had highlighted the accumulated burdens of the old regime and indicted its political, institutional, and ideological supports. The Republicans took control of the Senate for the first time in twenty-eight years, and, with the Democratic party in disarray, the administration quickly fashioned a working majority in the House of Representatives…His administration opened with a broadside assault on the ruling formulas of a bankrupt past: “In the present crisis, government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem.” This message would be hammered relentlessly over the next eight years, each blow directing the presidential battering ram against the institutions and principal clients of the liberal regime.” (Page 414.) Skowronek’s assessment in 1993 was prescient. In the election of 2016, the Republic Party celebrated gaining control of both houses of Congress, the White House, and 38 out of 50 state governments. As the following figures show, the Republican base in Congress has grown more conservative over time.

Perhaps the trend in Congress reflected the trend in the Republican voter base. The following figure shows growing conservatism among Republican voters.

Source: both graphs downloaded from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-fix/wp/2015/06/02/congress-sets-a-new-record-for-polarization-but-why/?utm_term=.89202ee3e5b9

Reflections for leaders

Reading Reagan’s memoir and various biographies of him highlight lessons about communication, delegation-and-control, determination, ideology, and character. To synthesize among these lessons, here are four final reflections.

1. Get a vision. What distinguished Reagan from Carter or Ford was his ability to plant a vision in the popular consciousness: the “city on a hill,” American exceptionalism, freedom from government intrusion, and pushback to socialism and communism. The difficulty of the “vision thing” would contribute to the downfall of Reagan’s successor, George H.W. Bush. A vision creates a sense of identity for the leader, making it easier for followers to know what the leader stands for. In my own experience as Dean, I found that alignment of a community around mission and vision made the rest of leading more fruitful (not necessarily easier, but more productive.)

2. Presence matters. So many observers argue that Reagan was the “Great Communicator.” But in watching videos of his speeches, one gets a sense that it was more than that. He had great presence. Reagan’s presence was a blend of folksy approachability and conservative determination. In contrast, Carter and Ford seemed awkward in the presidency—if they had any presence, it was due more to the office than the person. Presence contributes to the leader’s identity, but it also commands respect. Amy Cuddy and others have interesting books on developing leadership presence. My colleague, Lili Powell, teaches an excellent course on the subject.

3. Coordinator-in-chief. Reagan delegated too much and monitored too little. His famous saying, “trust but verify” worked in negotiating nuclear arms reductions with the Soviets, but was not observed in his oversight of Poindexter, North, and the Iran-Contra people. The President cannot manage all the details, but needs to balance delegation with monitoring.

4. Is a leadership model repeatable? The correspondence between Reagan and the candidacy and election of Donald Trump is eerie. One sees similar campaign mottoes (“Make America Great Again”), similar repudiation of elites and conventional thinking, and unusual communication skills and strategies. Will 2017 mark the beginning of one of Skowronek’s presidential cycles? The history of Reagan suggests that it will take a few decades to tell.

Works Referenced

Reagan, Ronald, An American Life, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1990.

Skowroneck, Stephen, The Politics Presidents Make: Leadership from John Adams to Bill Clinton, Cambridge: Belknap Harvard, 1993.

Weisberg, Jacob, Ronald Reagan, New York: Times Books, 2016.