Recently, the Darden teaching faculty gathered for a session in another of our series on teaching excellence—this one was led by colleagues Greg Fairchild and Jeanne Liedtka. They presented on the topic of “experiential learning,” which was both relevant and timely in view of the pressures from stakeholders of business schools who advocate for taking students “out of the box,” i.e., the standard classroom format.

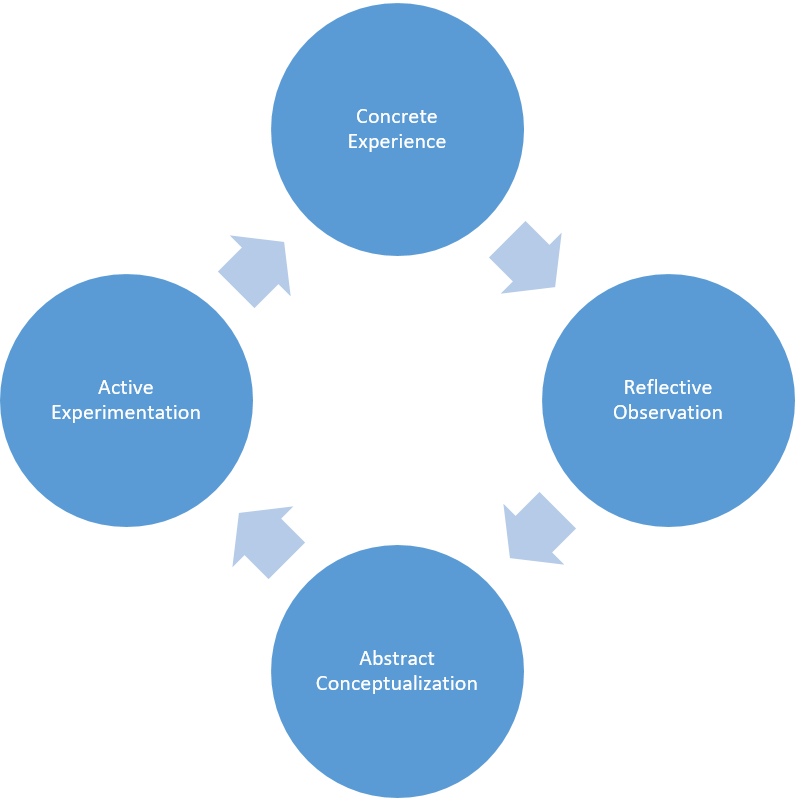

Fairchild and Liedtka defined experiential learning as “direct learning from life experience, not listening, reading, writing, or talking about it.” One learns from experience, reflection, development of concepts, and then experimentation with those concepts (a hands-on application)—this follows a model offered by David Kolb ((See David Kolb Experiential Learning: experience as the source of learning and development (Englewood Cliffs, Prentice Hall, 1984). Also see the brief discussion of the framework at https://www2.le.ac.uk/departments/gradschool/training/eresources/teaching/theories/kolb.))

As Jeanne said, “learning is not just experiential, but also experimental.”

Experiential learning offers several advantages over traditional formats. It accelerates learning; provides a safer environment for experimentation than does the real world; bridges the gap between theory and practice; engages emotions in a way that helps to trigger mindset changes; increases student engagement; develops reflective skills for lifelong learning; heightens responsibility for consequences; and increases commitment, effort, and attention in the learning process. Experiential learning can be a powerful because it is a fully embodied experience that harnesses all the senses and emotions to create stronger memory structures.

Greg and Jeanne surveyed colleagues’ use of various modes of experiential learning. These include simulations, field projects (both individual and group), competitive games, field trips, and experiments. It is one thing to say that a school uses modes of experiential learning. And it is another to say that they are used well. A considerable part of our discussion was focused on best practices for leading experiential learning, such as these:

- Allow plenty of time for debriefing after the experience. That is where the conceptualization occurs.

- The first run of an experience probably entailed mistakes; a second run permits the student to vary behavior, build on the learning from the first experience, and consider factors driving success or failure. Repetition permits the instructor to coach students between sessions and promotes conceptualization, the third stage of Kolb’s model.

- Build communities of practice. Teams, buzz groups, or online communities enable students to share and compare their experiences. This mutualization boosts the reflective process.

- Debrief thoughtfully. The instructor can promote reflection through careful questioning. Research ((See Jacobson, M. & Ruddy, M. (2004) Open to outcome (p. 2). Oklahoma City, OK: Wood ‘N’ Barnes.)) suggests the value of queries such as these:

- Did you notice…?

- Why did that happen?

- Does that happen in life?

- How can you use that?

- Planning: don’t just focus on classroom time; give serious consideration to what happens later.

- Promote the ability for students to see how other students learn. This invites students to see a shared experience through the learning of others.

- Establish class goals clearly and relate the learning experience to them explicitly.

- Have participants predict their performance before an experience and then evaluate how closely they matched their predictions.

- Prepare to offer social, emotional, and intellectual support to participants.

- Be strategic about the ambiguities you want participants to struggle with. Too much uncertainty can derail the learning and cause participants to questions your instructional design.

- Create/choose activities based on the quality of the debrief that they generate. Design with key take-aways or conversations in mind.

- Simplify where possible.

- In projects, prepare for clients who are sometimes more challenging than students.

- Consider very carefully the choices that you offer the learner. The act of choosing itself becomes the substance of learning.

- Have students check in with the instructor frequently to help avoid derailments.

- Pay attention to their emotional journey

- Address issues explicitly as you go with class

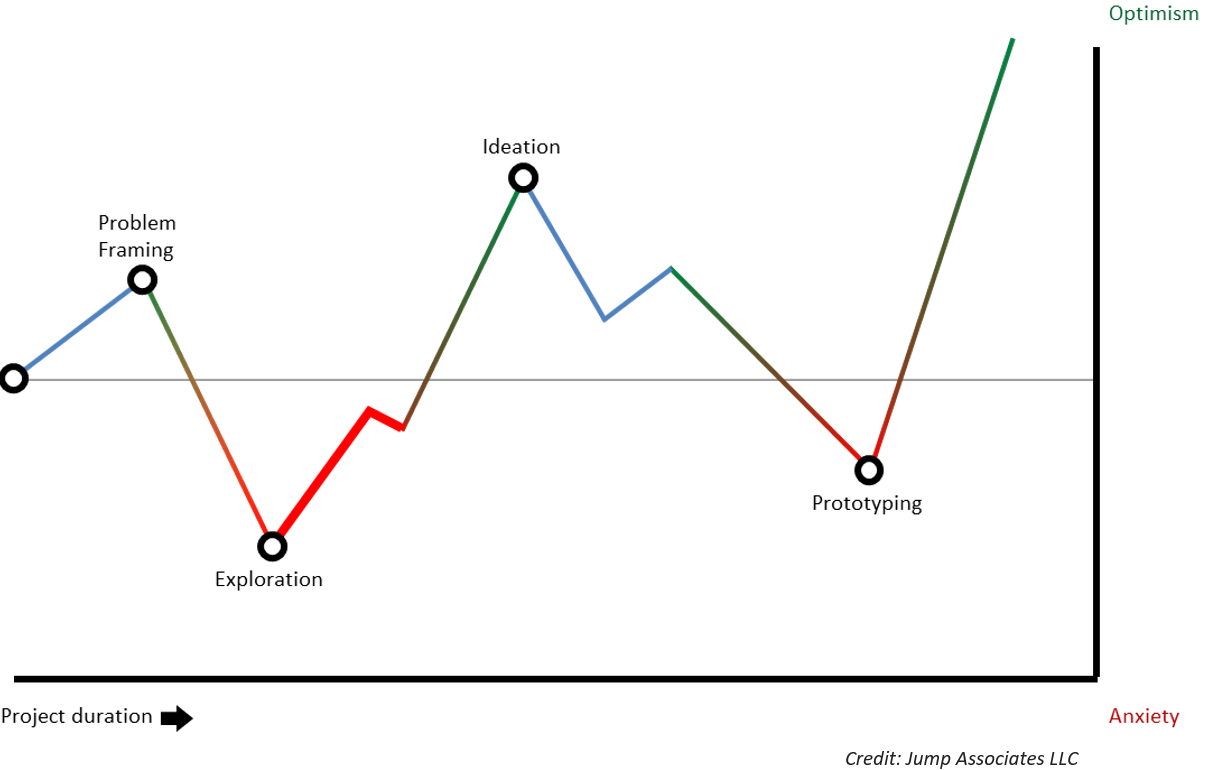

If experiential learning is so beneficial, what prevents its widespread use? It can be costly to set up; it can be challenging to grade students on it; some students may resist learning this way (they just want to be told); it might violate cultural norms about what constitutes a valid learning experience; the administrative structure of the school’s curriculum may not be sufficiently flexible to accommodate the experience; the faculty will experience a lack of control (of outcomes, process, and expectations); students might not be open to the experience; and ambiguity about an experience can generate student anxiety. Illustrating the emotional roller-coaster for students, Jeanne and Greg discussed the following graph of optimism/pessimism for experiential projects.

A coda: Darden’s teaching faculty members have been meeting this year on a variety of teaching topics. See the following for earlier discussions.