“I am a capitalist. I believe in free markets.”—Vice President Kamala Harris.[i]

“I am a capitalist, but pay your fair share.”—President Joe Biden.[ii]

“I am a capitalist. Come on. I believe in markets. What I don’t believe in is theft, what I don’t believe in is cheating.“ – Senator Elizabeth Warren.[iii]

[Representative Roger Williams (R-TX)] “Are you a socialist or are you a capitalist?

Mr. Corbat. Capitalist. [CEO of Citigroup]

Mr. Dimon. Capitalist. [Chairman and CEO JPMorgan Chase & Co.]

Mr. Gorman. I am a capitalist. [Chairman and CEO, Morgan Stanley]

Mr. Moynihan. Capitalist. [Chairman and CEO, Bank of America]

Mr. O’Hanley. Capitalist. [President & CEO, State Street Corporation]

Mr. Scharf. I am a capitalist. [Chairman & CEO Bank of New York Mellon Corp.]

Mr. Solomon. I am a capitalist. [Chairman & CEO, Goldman Sachs]

Mr. Williams. Well, it is a shutout for the socialists today.”

–Congressional Hearing, House Committee on Financial Services, April 10, 2019.[iv]

It takes a big tent to hold such a diversity of people who avow capitalism. What are the dimensions of that tent? What are the attributes of capitalism on which most people would agree?

It turns out that defining capitalism is not a simple matter. Wikipedia concludes, “There is no universally agreed upon definition of capitalism; it is unclear whether or not capitalism characterizes an entire society, a specific type of social order, or crucial components or elements of a society…Consequently, understanding of the concept of capitalism tends to be heavily influenced by opponents of capitalism.”[v] The recent recipient of the Nobel Prize in Economics, Daron Acemoglu, even proposed that the term be forgotten.[vi]

How big a problem is this? The dictionary folks at Merriam-Webster report an estimate of some one million words in the English language[vii]—surely “capitalism” isn’t the only slippery word in this tongue. But I would respond that the sheer impact of capitalism in the world today makes it worth parsing the word. But then, where do we look for clarity? Is historical or current usage any help? And can we be more precise about where people disagree about the term? And finally, is there a definition on which to get traction? In this post, I’ll tackle such questions.

(Un)common usage

Lexicographers tell us that a definition emerges from the way a word is commonly used. In the case of capitalism, the common usage approach presents at least two challenges.

First, capitalism itself has changed over time. Economist Joseph Schumpeter (1942) wrote that capitalism is a “process of industrial mutation…that incessantly revolutionizes the economic structure from within, incessantly destroying the old one, incessantly creating a new one.”[viii] In the terms of modern economics, capitalism is a complex adaptive system, in which participants respond to changing circumstances in ways that improve their chances of survival and success. Consequently, the incessant mutation of capitalism means that the frame of reference behind a definition of the word will vary over time. It seems likely that “capitalism” meant something different to Karl Marx and John Stuart Mill, who lived during the Great Industrial Revolution, than it means to those people quoted at the beginning of this post.

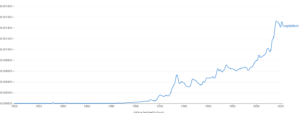

Second, the word, capitalism, seems to attract interest in times of stress. Though the Oxford English Dictionary identifies the earliest usage of capitalism in 1854, it took the rise of socialism and communism in the late 19th century for the word to gain broader usage. The following figure is an “Ngram” or graph of the percentage occurrence of “capitalism” in all English language books published annually from 1800 to 2023.

Figure 1: Ngram[ix] of “capitalism”

The figure shows very little use of “capitalism” before 1900, followed by several sharp increases: (a) 1916-1920, coincident with World War I, revolutions in countries such as Russia and Germany, and the rise of radical and anarchist movements in the U.S., Britain, and elsewhere; (b) 1929-1934, a big increase coincident with the onset of the Great Depression; (c) 1944-1947, associated with deprivation after World War II and concerns about return to depression; (d) a long slow rise from 1953 to 1975 coincident with the onset of the Cold War, the Vietnam War, and stagflation; (e) 1997-2002 a rise associated with the financial crises in Mexico, Asia, Russia, and the dot-com bubble and bust; and finally, (f) 2006-2018, a sharp increase coincident with the Global Financial Crisis and Great Recession. It seems that economic hardship and political instability prompt people to write about capitalism, times that challenge the functioning of market-based economies and summon calls for reform and radical change—hence, Wikipedia’s point that “the concept of capitalism tends to be heavily influenced by opponents of capitalism.”

Fault lines among definitions today

In my experience, people bring varying notions about capitalism to any discussion—this is likely true for the sample of people quoted at the start of this post. To save you a laborious slog through the attributes of the many definitions, I’ll illustrate the complexity of definitions with a summary of three “fault lines” or debates that a definition tends to generate. Mind you, a definition doesn’t have to be either/or; it could nod to both sides of a debate. But what a definition emphasizes tends to hint at where the writer is going.

Fault line #1: Does “capitalism” apply mainly to social conditions or to economic circumstances? Those of radical persuasion tend to come at capitalism from the sociological corner, arguing that capitalism values profits over environment, efficiency over equity, and self-interest over the interest of others. In his three-volume Das Kapital, Karl Marx never actually defined capitalism, other than to assert that it is a stage in the historical development of society, associated with the advent of economic classes, including the bourgeoisie and the proletariat. He argued that the boom-bust business cycle of market economies revealed internal contradictions that would doom the sustainability of capitalism. Marx today is regarded as a weak economist but an astute sociologist, a good observer of social conditions and trends in his day. He needed a foil, against which to critique the social impact of the Great Industrial Revolution and found it in the capitalists who financed it. Other critics will point to greed as a defining attribute of the system and cite waste, inefficiency, externalities, and market failures as its hallmarks, without recognizing that no other system avoids these either.

The other view is that capitalism is an economic thing motivated by self-interest that promotes efficiency and higher welfare. The godfather of economics, Adam Smith, in his Wealth of Nations (1776), wrote, “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.”[x] Some critics misunderstand self-interest to mean greed, but the two are quite different. Greed is a craving, an overwhelming desire, that is intense, excessive, and repellent to society, violating moral norms. We recoil from a greedy person because, as Adam Smith argued in his other classic book (The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759)), greed overwhelms sympathy for fellow beings. Self-interest best captures the benign motivation for daily decisions by billions of people in capitalist economies. Self-interest prompts people to use their resources to best effect, meaning most efficiently. So Adam Smith argues that when many people behave in their self-interest, the result is a rise in general welfare:

“…every individual necessarily labours to render the annual revenue of the society as great as he can. He generally, indeed, neither intends to promote the public interest, nor knows how much he is promoting it. … he intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention. Nor is it always the worse for the society that it was no part of it. By pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it.[xi]

Fault line #2: Is capitalism mainly about the private ownership of the means of production, or making a profit, or the voluntary exchange of goods and services in markets? For instance, many of the modern definitions of capitalism start with the notion of private ownership of the means of production. A prime example is the entry in the authoritative Oxford English Dictionary: “capitalism The condition of possessing capital; the position of a capitalist; a system which favours the existence of capitalists.”[xii] That’s all? The OED’s definition is a disappointment. It focuses on possession of property and neglects so much more that participants in capitalist systems encounter daily, such as buying and selling, competition, investment, and the respect for (or violation of) civil rights. And implicitly, this definition begs a comparison of capitalism with public ownership of the means of production (that is, socialism). Is it really necessary to define something by reference to that which it is not?

Another definition says that “Capitalism is essentially the investment of money in the expectation of making a profit.”[xiii] Investment is surely an aspect of capitalist activity; and profit-making is surely a desired outcome. But to start there? I think not. The estimable Peter Drucker expressed a truth that business people across the world confront daily: the first purpose of a business is to create and keep a customer.[xiv] Most savvy investors would not put their money into a business that could not answer the question, “Who is your customer?” To begin with a focus on a customer is to shape a value proposition that will lead to a sale, an exchange of money in return for a good or service.

This leads to a third possible definition of capitalism that begins with a focus on voluntary exchange, without which other defining attributes of capitalism make little sense. The idea of exchange embraces the existence of markets, which are the institutional embodiments of capitalism. But for capitalism to work, exchange needs to be without compulsion—hence, the word, “voluntary.” In The Godfather, a gangster says, “I’ll make him an offer he can’t refuse,”[xv] meaning that it would be an involuntary exchange. Markets with voluntary exchange preclude restrictions on price-setting such as price controls, rationing, and exclusionary laws and practices (like the racist Jim Crow laws). However, to ensure the fairness of prices—the mechanism by which resource allocation is determined—requires fair dealing, open competition, easy entry by buyers and sellers, property rights, and the sanctity of contracts. This introduces the necessity of constraints on behavior imposed by norms, laws, civil and commercial rights, standards, and a system of justice, what economists call “institutions”—these must be features, not bugs, of daily life in a capitalist system. Even in a world without government, market participants tend to form their own sophisticated systems of contract monitoring and enforcement—such was true, for instance, among merchants on the Silk Road of the 12th century. As Martin Wolf wrote, “Without the rule of law, there can be no market capitalism, just larceny.”[xvi]

The point is that simply defining capitalism by private ownership or profits ignores so much more that constitutes the daily experience of participants in the capitalist system.

Fault line #3: Does capitalism exist only in this pure theoretical form or can the notion embrace many possible variants seen in the real world today? Textbook definitions of capitalism tend to refer to an idealized setting that is absent any imperfections about competition, information, rights, or government. Yet, participants in market economies today will witness variations in what is advertised as a capitalist system. Is the standard definition sufficient, or do very different economic systems reside under the general name of “capitalism?”

Consider whether capitalism in the U.S. is the same as capitalism in China. In 2019, Branko Milanovic asserted that capitalism was the dominant and enduring economic system in the world and that countries such as the United States and China were economically equivalent—that there was one system, and that functionally the system was the same from country to country. In reviewing Milanovic’s book a year later, Robert Kuttner (2020) wrote that Milanovic’s “discussion is …an oversimplified description of the world’s economies and a misleading summary of China.”[xvii] The difficulty with abstract definitions of capitalism is that they skirt the possibility of variants.

Peter Hall and David Soskice[xviii] argued that nations develop clusters of institutions (laws, norms, and cultural practices) that reinforce each other and form “the way we do things here.” Capitalist economies vary in the extent of government intervention in markets and can exist as sub-economies even within socialist and centrally planned systems.

- Liberal market capitalism. One group of countries tends to cluster around relying on markets to coordinate the allocation of resources in an economy—this view characterized the “Anglo-American” sphere: United States, Canada, United Kingdom, Ireland, Australia, and New Zealand. The system in these countries reflected relatively less regulation of the private economy, a smaller social safety net, and corporate governance that placed a priority on the welfare of the owners of firms. It is important to reflect that even the U.S. is not a pure capitalist system, free of government intervention. Instead, the role of government in U.S. markets is massive. In 2022, government spending accounted for 36% of U.S. gross domestic product.[xix] Subsidies, incentives, trade protections or restrictions, and regulations exert enormous influence over the conduct of business in pillars of the private economy such as agriculture, defense, telecommunications, construction, health care, transportation, finance, and foreign trade. In short, the U.S., often caricatured as a bastion of “free market capitalism,” is more accurately a “mixed economy” of public and private direction.

- Coordinated market capitalism, Hall and Soskice said that some other countries relied more on state-motivated coordination among participants in markets to pursue higher economic and social outcomes—examples would be Germany, Japan, Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland. The system in these countries reflects somewhat more regulation of the private sector, a larger social safety net, and corporate governance that includes representation by workers, shareholders, and possibly other groups on the boards of private-sector firms.

- State capitalist systems. Ian Bremmer, a prominent country risk analyst, characterized a form of capitalism in which “the state acts as the dominant economic player and uses markets primarily for political gain.”[xx] He said that the instruments of state capitalist countries include strategic control over natural resource exports, subsidization of the expenses of private domestic companies to enable them to export at advantageous prices and to dominate strategic global markets, and the deployment of sovereign wealth funds to invest in foreign firms. State capitalist countries, he said, are not motivated by profits or value creation, and instead aim to achieve geopolitical advantage.

- Social democracy. This system mixes capitalism with a strong welfare state, policies toward economic equality, universally accessible public provision of health care, child care, elder care, and the strong regulation of privately-owned enterprises in the public interest. The emphasis on social democracy points to resistance to authoritarian rule. Rather socialist ideals are to be realized through democratic means, in a slow and peaceful transformation of the economy. Tony Blair, former Prime Minister of the UK, called this the “Third Way,” a blend of economically liberal policies with social democratic processes, a middle way between capitalism and socialism. Social democrats today include the Social Democratic Party of Germany, the Swedish Social Democratic Party, and the Progressive Alliance.

- Democratic socialism. An economic system in which industries are publicly owned, though some property (such as homes, small businesses, vehicles, and household goods) may be privately owned within government limits against excessive accumulation. The government closely regulates the economy. The profitability of all enterprises is subordinated to social welfare and the provision of social services. Some private enterprises are allowed as a supplement to services provided by the state.

- Centrally planned economies figure importantly in Cuba, Iran, North Korea, Venezuela, and Zimbabwe. In these countries the government exercises controls on virtually all economic activity, including prices, capital allocation, and the mobility of labor. But even the official sanction for central planning in these countries cannot disguise the prevalence of black and grey market systems of exchange.

Numerous other models and names for economic systems exist along a spectrum from liberal to centrally planned economies.

Is this laboring over definitions a waste of time?

No. I think the definition of capitalism is too important to fudge. Whether one likes capitalism, hates it, or likes it enough to want to reform it, clarity about the definition of capitalism is essential for at least four reasons: a) its material role in the world, b) its association with advancement in human welfare, c) its claims of moral legitimacy, and d) the wave of criticism that capitalism has received in recent years (see my related posts on capitalism).

Materiality. Understanding capitalism is essential to understanding the modern world. Capitalism is the “only game in town,” the significant, if not dominant, economic system today. In 2020, market economies accounted for about 60% of global GDP.[xxi]

Well-being. From 1991 to 2019, the number of people living in extreme poverty fell from 2 billion to 648 million.[xxii] This stunning achievement is attributable to many causes, including sustained economic growth, rising international trade, and the development of domestic markets and legal institutions enabling investment and market exchange—in other words, the spread of capitalism.[xxiii] And capitalism is associated with the commercialization of new goods and services in many fields such as health care, electric power, transportation, and communication that have raised the quality of life.

Moral legitimacy. Many of the criticisms of capitalism assert that it is immoral, a system of fraud, theft, and exploitation, or that it is at least amoral, devoid of moral claims. Yet numerous writers have asserted the opposite. Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations (1776), informed by his earlier Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759), emphasized that market exchange and division of labor (two of the early defining attributes of capitalism) married virtues such as self-interest and sympathy, justice and beneficence, prudence and risk-taking. Max Weber (1930) argued that capitalism is motivated by morality rather than greed; and he linked the rise of capitalism to values about work, calling, prudence, and saving that he deemed were promoted by the Reformation. Friedrich Hayek (1944) argued that capitalism is a creative force that liberates individuals. Hayek and others have asserted that the spread of capitalism globally is associated with the growth of democratic systems of government, that capitalism and democracy are mutually-reinforcing. Even Pope John Paul II acknowledged that “the free market is the most efficient instrument for utilizing resources and effectively responding to needs.”[xxiv] To be clear, debates continue about these and other claims of moral legitimacy. Nonetheless, these claims invite clarity and scrutiny about what “capitalism” means.

Conclusion

So, what are we to make about the avowals of capitalism by the range of figures at the beginning of this post? A big takeaway must be that capitalism is difficult to define and ideologically loaded—if you have a political agenda, you are likely to favor one definition over another. Common usage of the word has been (and is) divergent enough as to challenge the listener. To hear “I favor capitalism,” begs “what kind?” Absent in the speeches and interviews from which the quotations are taken are explanations of what the word means to the speakers.

Capitalism is a “big tent” idea that can attract adherents who bring very different ideas to the notion. I sketched three fault lines (there are probably many others) within the big tent: a) whether the proponent defines the system by attributes of efficiency or inequity; b) whether capitalism is mainly about private property, profits, or voluntary exchange; and c) whether capitalism exists only in a perfect world or can exist in many forms dictated by an imperfect world.

Asking the Internet to define capitalism summons about 183,000 results. Yet the babble of definitions should not daunt you. I argued that the materiality of capitalism, its benefits to the world, and its claims to moral legitimacy should motivate business leaders, government policymakers, researchers and educators to rally around a definition that makes sense.

To start a reflective process—either to encourage or provoke you–let me close with my own preferred definition. Admittedly, this succumbs to my earlier criticism of textbook-style definitions, as it falls into the category of abstraction and neglects the many possible variations. But perhaps it will serve as a starting point for your own reflections: [xxv]

Capitalism. An economic system based on voluntary exchange among buyers and sellers in which prices and other information drive the allocation of resources, competition and specialization promote efficiency, self-interest motivates decision-making, and personal investment creates private property, all of which are sustained by civil rights and institutions.

I favor this definition over others because the words convey the concept of capitalism in useful depth. Let’s parse the words.

Exchange means bargaining between buyers and sellers over prices and other terms. The existence of exchange is the fundamental attribute of capitalism, without which the rest makes no sense—I have not seen a definition in a prominent dictionary that incorporates this word. The idea of exchange—the focus on buying and selling—springs from Peter Drucker’s notion that the purpose of a business is to create and keep a customer. And it embraces the existence of markets, which are the institutional embodiments of capitalism.

Voluntary means without compulsion, owing, for instance, to unequal bargaining power, threats, price controls, rationing, or exclusionary laws and practices. However, voluntary does not mean anarchic, absent of any constraints. We all accept the observance of general rights, laws, norms, and other institutions as conditions for participation in society. For instance, we drive on the correct side of the road for safety; we pay for transactions with legal tender currency for convenience; we fulfill promises, without which a market economy would falter.

Self-interest motivates bargaining for exchange. Self-interest implies that the decision-maker routinely asks, “Am I better off with opportunity A versus B?”—and then decides consistently with one’s welfare. Self-interest best captures the benign motivation for daily decisions by billions of people in capitalist economies.

Allocation of resources[xxvi] responds to the information generated by exchanges, such as prices, terms of payment, timing of delivery, and quality of goods or services and other aspects of an exchange. Motivated by self-interest, participants in markets will want to use their resources to best effect, meaning most efficiently—this is Adam Smith’s “invisible hand.”

Competition among producers and customers drives efficiency and specialization. To an outsider, having many producers in a market seems wasteful—wouldn’t it be better to have just one producer? Indeed, some business executives pine for the quiet life of monopoly, where one would not have to scramble for customers, constantly tinker to improve products, and best of all, where one could set prices as high as one wants.

Private ownership arises from the use of private resources to fund the participation in markets and exchanges. In addition, private ownership motivates and amplifies self-interest. Finally, private ownership compels the need for property rights and other institutions.

Civil rights and institutions ensure the sustainability of a capitalist system. Paramount among these are rights to claims on private property, the sanctity of contract, the rule of law, and a system of justice that enforces them.

End Notes

[i]Kamala Harris, CNBC-TV18, September 28, 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o8nGbCEwu-k.

[ii] Joe Biden, YouTube, February 8, 2023. https://www.google.com/search?q=%22I+am+a+capitalist%22&rlz=1C1GCEA_enUS1126US1126&oq=%22I+am+a+capitalist%22&gs_lcrp=EgZjaHJvbWUyBggAEEUYOTIICAEQABgWGB4yCAgCEAAYFhgeMggIAxAAGBYYHjIICAQQABgWGB4yCAgFEAAYFhgeMg0IBhAAGIYDGIAEGIoFMg0IBxAAGIYDGIAEGIoFMg0ICBAAGIYDGIAEGIoFMgoICRAAGIAEGKIE0gEINDI5M2owajSoAgCwAgE&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8.

[iii] Elizabeth Warren, CNBC, July 24, 2018. https://www.cnbc.com/2018/07/23/elizabeth-warren-i-am-a-capitalist-but-markets-need-rules.html.

[iv] U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on Financial Services, April 10, 2019, https://www.congress.gov/event/116th-congress/house-event/LC64813/text.

[v] Wikipedia, October 5, 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Capitalism#:~:text=Capitalism%20is%20an%20economic%20system%20based%20on%20the%20private.

[vi] Acemoglu, Daron (2017). “Capitalism”. In Frey, Bruno S.; Iselin, David (eds.). Economic Ideas You Should Forget. Springer. pp. 1–3. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-47458-8_1. ISBN 978-3-319-47457-1.

[vii] See https://www.merriam-webster.com/help/faq-how-many-english-words.

[viii] Schumpeter (1942) 83.

[ix] An Ngram is a sequence of letters (or symbols) in a particular order. The Google NGRAM viewer counts the occurrence of books containing the word, “capitalism,” published each year from 1800 to 2022 and divides that annual count by the total number of books published each year.

[x] Smith, Adam. 1776(2005). An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. London: W. Strahan & T. Cadell, p. 19. An Electronic Classics Series Publication, accessed October 7, 2024, https://www.rrojasdatabank.info/Wealth-Nations.pdf.

[xi] Smith, Adam. 1776 (2005). An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. Vol. II (1st ed.). London: W. Strahan & T. Cadell. p. 364. An Electronic Classics Series Publication, accessed October 7, 2024, https://www.rrojasdatabank.info/Wealth-Nations.pdf.

[xii] Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed., 1989, Vol. 2, p. 863.

[xiii] Fulcher, James, 2015. Capitalism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, p. 2.

[xiv] See Peter Drucker, 1975. The Practice of Business, Chapter 7 generally and page 67 in particular.

[xv] Puzo, Mario and Francis Ford Coppola, 1971. The Godfather, screenplay downloaded October 25, 2024, from https://www.dailyscript.com/scripts/The_Godfather.html.

[xvi] Wolf 2024, page 6.

[xvii] Robert Kuttner, “Can We Fix Capitalism” New York Review of Books, September 20, 2020, page 71.

[xviii] For further discussion of liberal market capitalism and coordinated market capitalism, see Peter A. Hall and David Soskice, Varieties of Capitalism, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

[xix] Data from the International Monetary Fund, downloaded October 25, 2024 from https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/profile/USA.

[xx] For a discussion of state capitalism, see Ian Bremmer, The End of the Free Market: Who Wins the War Between States and Corporations? New York: Portfolio, 2010.

[xxi] Taking as a rough sample of free market economies, the members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) accounted for aggregate GDP of $58 trillion in 2021, compared with an estimated global GDP of $96 trillion. (Source: The World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=OE.)

[xxii] Source: pip.worldbank.org/home.

[xxiii] Rogers, James R., 2013. “What’s Behind the Stunning Decrease in Global Poverty?” First Things, November 26, downloaded February 1, 2023 from https://www.firstthings.com/web-exclusives/2013/11/whats-behind-the-stunning-decrease-in-global-poverty. Also see Tompkins, Lucy, 2021. “Extreme Poverty Has Been Sharply Cut. What Has Changed?” New York Times, Dec. 2, downloaded February 1, 2023 from https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/02/world/global-poverty-united-nations.html.

[xxiv] Pope John Paul, Centesimus Annus (1991) page 34.

[xxv] After writing this definition, I found a lengthier one offered by the International Monetary Fund, which shares many of the same features. I commend it. See Sarwat Jahan and Ahmed Saber Mahmud, (undated). “Free markets may not be perfect but they are probably the best way to organize an economy” downloaded October 7, 2024. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/Series/Back-to-Basics/Capitalism#:~:text=In%20a%20capitalist%20economy%2C%20capital,%E2%80%9CSupply%20and%20Demand%E2%80%9D).

[xxvi] “Resources” means more than money—it could include land, machinery, patents, digital code, artistic works, special know-how, and the employees in a firm.