As I write this concluding post for the fall semester, the present context gives more meaning to our readings about the Great Depression. Donald Trump’s startling win in the Presidential election, the buoyant estimates for infrastructure spending (maybe $1 trillion) under the new administration, and the vaulting gains in the stock market invite two questions. First, is the new talk about higher economic growth for real? Second, what kind of fiscal stimulus is consistent with the higher growth outlook? This isn’t the place to try to answer those questions. But if economic growth is the topic du jour, then our recent reading and discussion were very timely.

For the fourth meeting of our seminar, Richard A. Mayo and I assigned Barry Eichengreen’s The Hall of Mirrors: The Great Depression, the Great Recession, and the Uses—and Misuses—of History. This session afforded an economic “long view” of the entire period, afforded a comparison with the Great Recession of 2009-2015, and raised several conceptual points.

The Long View: 1929-1939

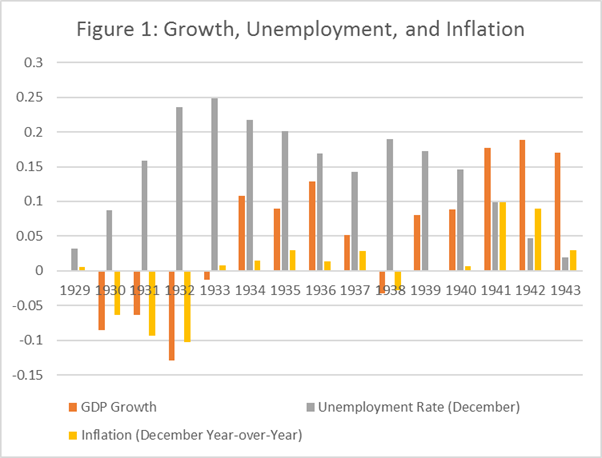

The depths reached in the Great Depression between 1929 and 1933 were bad enough to qualify it for the record books. But equally stunning was the duration of under-performance. Popular thinking considers that the Depression ran until 1939. But as Figure 1 shows, unemployment did not fall below the level of December 1929 until 1943.

Source: Author’s graph, with data from https://www.thebalance.com/us-gdp-by-year-3305543

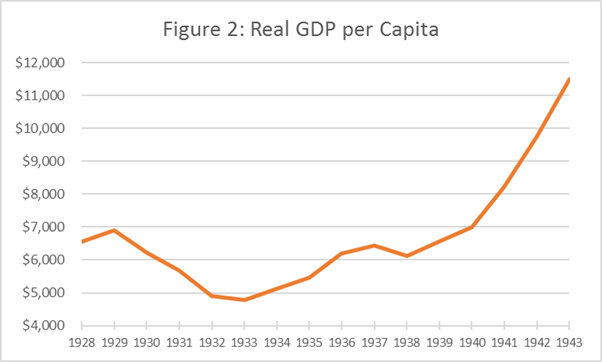

And after the breathtaking deflation of 1930-1932, prices would not surpass the level of 1928 until 1942. But the conventional measure of economic welfare, Gross Domestic Product per Capita, surpassed the previous peak (1929) as late as 1940 (see Figure 2).

Source: Author’s graph, with data based on estimates by Angus Maddison, from http://socialdemocracy21stcentury.blogspot.com/2012/09/us-real-per-capita-gdp-from-18702001.html.

Visible in the two graphs is the fact that the Great Depression actually consisted of two slumps: 1929-1933 and 1937-38. In between was an episode of healthy per capita GDP growth of 7.05% (1934), 6.9% (1935), and a whopping 13.5% (1936).

The year, 1936, proved pivotal not only for economic growth, but for several new themes that enriched further our understanding of the Great Depression.

1. Rise of populism. Social and civic stress blossomed into various kinds of social protest. Labor unions strengthened and struck. Radio broadcaster Father Charles Coughlin fanned popular anger with virulent anti-establishment, anti-elite, anti-semitic, and nationalistic messages. Senator Huey Long sought to “make every man a king” through a “share the wealth program.” Communist sympathizers pointed to the supposedly robust health of the USSR and excoriated the capitalist system. Fascists pointed to Hitler and Mussolini as exemplars for fixing American government. The populist sentiments pulled FDR to the left in an effort to retain his coalition. Indeed, his speeches and messages criticized monopoly power, the wealthy, and private enterprise as causes of the slow recovery; the President attacked “economic royalists.” This change in tone had the effect of legitimizing the message of social protest and alarming business decision-makers. Robert Higgs has argued that the intervention in markets, rising regulation, and hostility toward business created investment uncertainty that brought on the second slump. In contrast, Barry Eichengreen cites rising labor costs as a depressant on economic growth in the late 1930s, reflecting growing union militancy.

2. Shift from reform to relief. The legislative record of FDR’s first term substantially consisted of new laws and regulations designed to make the economic system fairer and more stable, and to promote recovery. FDR sought to “save capitalism” by reforming the system. In December, 1933, John Maynard Keynes had written to FDR, criticizing him for emphasizing reform over relief. Notwithstanding the legislative successes of his first term, employment had not recovered. Furthermore, the Supreme Court ruled unconstitutional the National Industrial Recovery Act (the centerpiece of FDR’s reforms) and other New Deal laws. Shortly after his re-election, FDR sought to “pack” the Supreme Court by increasing the number of justices from nine to 15; but Congress balked. With that, FDR pivoted toward policies by which the government itself would put people to work. The so-called “Second New Deal” successfully passed the Works Progress Administration (to give unemployed Americans jobs), the Wagner Act (to give labor unions the right to organize), and the Social Security Act (to give assistance to the aged, the unemployed, dependent children and the blind.) Moreover, FDR abandoned a commitment to balance the federal budget and endorsed deficit spending as a stimulus to economic growth. Finally, FDR reorganized the Executive Branch and creating the Executive Office of the President to give him more targeted advice with which to motivate and direct the bureaucracy.

3. From national toward international. American sentiment was isolationist during the 1930s. FDR was an economic nationalist during his first term. And between 1935 and 1939, Congress enacted five neutrality laws to prevent engagement in foreign wars. Isolationism was a natural outgrowth of the Depression and the memory of defaulted loans that financed allies in World War I. However, Japan’s full-scale invasion of China in 1937, Stalin’s “Great Purge” of 1937-38, Germany’s occupation of the Rhineland in 1936 and annexation of Austria and Czechoslovakia in 1938, and the Spanish Civil War of 1936-38 awakened American policy makers to threats to world peace. With the commencement of hostilities in Europe on September 1, 1939, FDR formalized aid to China and Britain.

To this narrative of the lengthy unfolding of the Great Depression, Barry Eichengreen’s Hall of Mirrors brings a valuable perspective on at least three topics.

Why the Depression lasted so long. Eichengreen points to the steep trajectory of recovery from 1933 to 1936 and implies that at that rate, the depression would have ended soon. Indeed, looking at Figure 2 and extending the slope of recovery in 1936 forward in time, it seems plausible that the Depression would have returned to pre-crash GDP per capita in the next year. Eichengreen argues that the second downturn was the result of two policy errors: fiscal austerity and monetary tightening. He wrote,

“It thus took a concerted effort by everyone from FDR on down to produce another recession. The president had again become obsessed with balancing the budget. Large deficits, as he saw it, were a sign that the economy was still ill. Balancing the budget , on the other hand, would signal that the emergency was over. Doing so would give a welcome boost to confidence. Not for the last time in the annals of economic policy , there was also an element of political expediency involved. Having campaigned in 1932 on a promise to balance the budget, FDR became fixated on the idea with the approach of the 1936 election. It was not so much criticism from the Republican Right that the president feared. Rather, he worried about a challenge from the Left in the person of the radio priest Father Charles Coughlin, who…turned against him on the grounds that the New Deal was insufficiently ambitious; it marked “two years of surrender, two years of matching the puerile, puny brains of idealists against the virile viciousness of business and finance, two years of economic failure.”…Thus, balancing the budget and populist tax policies could go hand in hand. This political strategy led FDR to push, and the Democrat-controlled Congress to agree to, higher taxes…More important, surely, was the restrictive turn in monetary policy…The decision by the Federal Reserve Board…to raise reserve requirements from 13 to 19.5 percent in August 1936, 22.5 percent in March 1937, and 26 percent in May was intended to restore the effrectiveness of the central bank’s conventional policy tools…Treasury Secretary Morgenthau was among those preoccupied by the specter of inflation…To neutralize the inflationary threat, the Treasury Department now sold bonds from its portfolio…mopping up the additional cash and removing it from circulation.” (Pages 266-270.)

The combined impact of actions by the Fed, Treasury, and President was highly contractionary. Eichengreen seems to suggest that none of the three parties took a systems view or tried to understand that together they would nip recovery in the bud.

The Great Depression versus the Great Recession. Hall of Mirrors is an impressive exercise in the comparison of two economic calamities. Chapters of the book interleave episodes of the two events. This literary approach was probably adopted to promote comparisons. But the back-and-forth induces chronological whiplash. The grand takeaway is that government policy makers in 2008-9 may have averted a second Great Depression, but that the long duration and slow recovery stemmed from some of the same errors as Hoover, FDR, and associates. What went well in 2008-2014 was the generally stimulative monetary policy of central banks. On the other side of the ledger, regulatory stabilization of financial institutions was inconsistent (think of Lehman); fiscal stimulus was too soon and where it occurred, petered out too early; given the absence of fiscal unity, the European Monetary Union seemed doomed to fail; and the lapse into fiscal austerity in the U.S. and Europe in 2010 choked off growth.

Economic theories about growth. Eichengreen argues from Keynesian principles that the length of the Great Depression and Great Recession were due to policy errors that favored austerity. The classical Keynesian view is that downturns are attributable to slackening demand and can be reversed by government-sponsored stimulus, especially by deficit spending. Keynes envisions that a dollar spent by government will result in more than a dollar of economic output; therefore, stimulus spending by the government can help to restore economic growth.

On the other hand, neoclassical economists take the view that consumers, managers, and investors make economic decisions by looking at tradeoffs. Therefore, cyclical downturns are due to distortions in decision-making that adversely influence the production and consumption of goods and services—what matters are the expectations of decision-makers. Thus, Robert Barro argues that the spending multiplier might well be less than one, if an added dollar spent by the government means higher taxes and lower growth in the future to repay the debt incurred today. In particular, supply-side economists assert that the supply of labor, products, services, and money creates demand. Therefore, the government should deregulate and reduce tax rates to stimulate growth. Lee Ohanian, an economist at UCLA, reviewed Hall of Mirrors and took a different view from Eichengreen and argued that government interventions in the Great Depression and in the Great Recession prevented the normal return to growth.

In short, one side would urge governments to fight a depression by stimulating the economy through fiscal spending. The other side would urge relaxing the temptation to intervene.

Conclusion: the value of historical comparisons

If economists can’t agree on what causes depressions and recessions, why should we engage in the exercise of comparing the crises? (President Harry Truman famously said that if you laid economists end to end, they would point in all directions.) The deeper question is why study history at all? Eichengreen responds,

“The historical past is a rich repository of analogies that shape perceptions and guide public policy decisions. Those analogies are especially influential in crises, when there is no time for reflection. They are particularly potent when so-called experts are unable to agree on a framework for careful analytic reasoning. They carry the most weight when there is a close correspondence between current events and an earlier historical episode. And they resonate most powerfully when an episode is a defining moment for a country and society.” (Page 377.)

Economic and financial crises are messy and chaotic events. There is no checklist or handbook to tell decision-makers what to do. Under such circumstances, it seems reasonable to look at precedents for inspiration about what to do and for caution about what not to do. In that respect, Hall of Mirrors helps to build our frame of reference by recounting two economic calamities. While it is true that more can be said about these episodes, the book is a valuable foundation for critical thinking when (not if) we enter the next calamity.

Works Referenced

Robert J. Barro, “Government Spending is No Free Lunch,” Wall Street Journal, January 22, 2009.