What would you think if someone told you that the source of your water supply is being grossly overused, is now less than half full, is losing another 6% every year, and will become unavailable to more and more people in coming years?

The coronavirus has nothing to do with this.

But this is reality for the more than 40 million Americans who depend upon the Colorado River for their drinking water, farm irrigation, or electricity production.

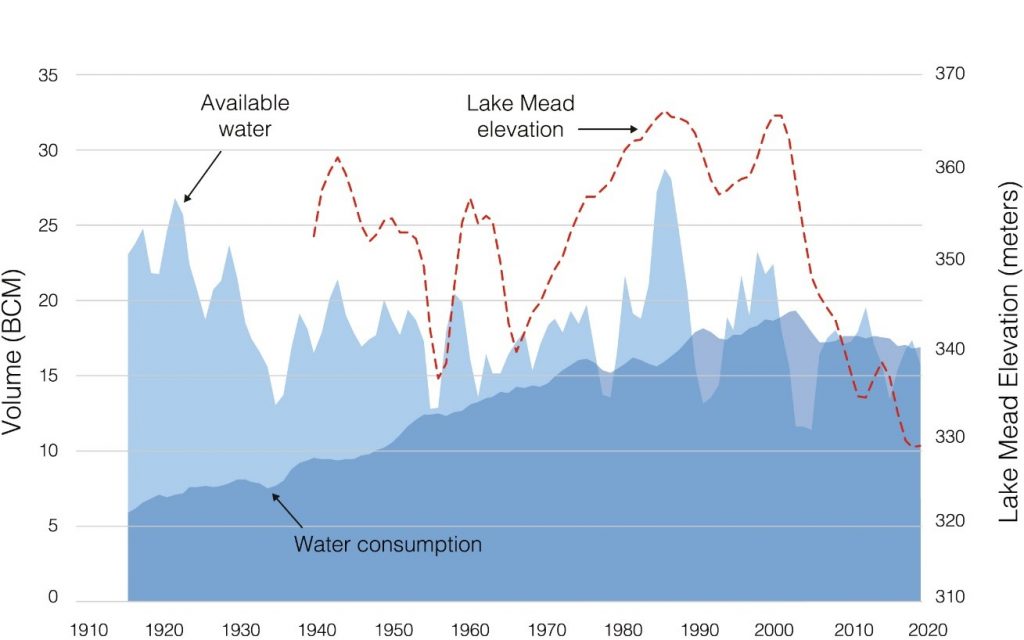

It should have been easy to see this crisis coming. After all, consumption of water from the Colorado River began to exceed the river’s annual flow way back in the early 1980s (see graph below). In most years, more water is removed from the river than is available to refill its large reservoirs (Lake Mead and Lake Powell), and as a result, those reservoirs are now less than half full. Lake Mead is encircled by a 35-meter-high, white chalky “bathtub ring” that indicates how far the water level has fallen.

Water availability and use in the Colorado River basin. Over the past century, consumptive water uses in the basin increased steadily, to the point that annual consumption exceeded total river flows in 75% of years from 2000 to 2015. This overconsumption has dried the river at its delta in Mexico and progressively depleted major storage reservoirs in the basin, including Lake Mead, posing severe risk of water shortage. All variables are portrayed as three-year running averages; BCM = billion cubic meters. Data source: US Bureau of Reclamation. Graph from Richter et al. (2020).

The reservoir levels are expected to continue dropping because, on average, 18% more water is being consumed than the river produces each year. Worse yet, climate scientists are warning that the river’s flow will decline by another 30% by 2050 due to climate warming. That means that to bring the river system back into long-term sustainable balance, those dependent on the river’s water will need to cut their demands in half by mid-century!

Can Academic Research Help?

Unsurprisingly, there is a great deal of discussion and debate over what to do about this water crisis. As academic researchers, we are drawn to predicaments like these because there is always a need for more and better information for decision-making.

Fortuitously, Peter Debaere, a Darden professor and head of the Global Water Initiative at UVA, and his post-doc Tianshu Li have been working with a multi-university research team (including me) organized under a food-energy-water program funded by the National Science Foundation. This group is focused on gaining an understanding of how and where the consumer goods produced and sold in America affect our collective use of water and energy.

One of the big questions we wanted to answer for the Colorado River and many other rivers across the water-stressed western United States was: “Where is all the water going?”

As initial research results became available, some of our findings stunned us: 86% of all the water consumed in the western United States is used for crop irrigation, and nearly 40% of that irrigation water goes to watering two crops—alfalfa and grass hay—that are used to feed cows for beef and dairy production. In the Colorado River basin, 55% of all water consumed goes to these two cattle-feed crops.

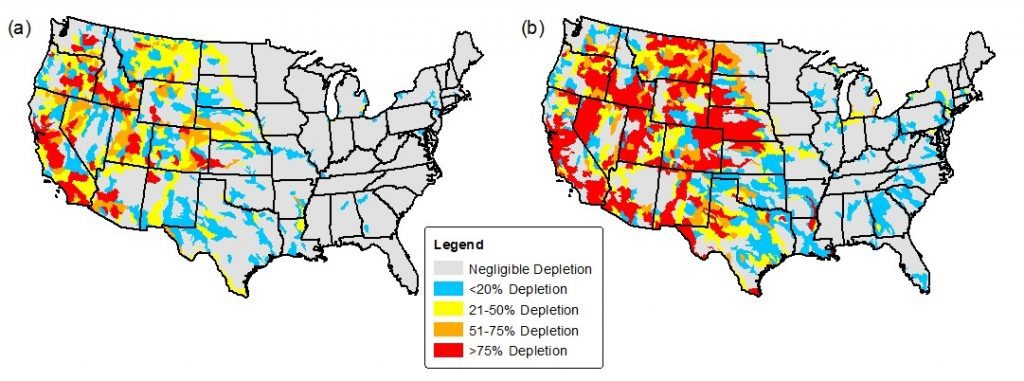

We then developed hydrologic and ecological models to give us insights into the specific impacts of different types of water use. We found that during droughts, human uses of water deplete one-fourth of all rivers and streams in the West to near exhaustion, and irrigation of cattle-feed crops accounts for more than half of water extracted from these depleted rivers. We also found that irrigating cattle-feed crops is responsible for increased extinction risk in more than 50 native fish species.

Depletion of river flow across the United States during summer months. The 17 western states experience much higher levels of depletion during July to September than do eastern states, owing to less precipitation and greater use of irrigation in the western states. (a) Summer depletion during the 2001–2015 model simulation. (b) Summer depletion in the driest 10% of years during 1961–2015. From Richter et al. (2020)

Some members of our research team then wanted to know where the beef and dairy goods produced using water from stressed rivers like the Colorado end up. We found, for example, that the volume of “virtual” Colorado River water embedded in the beef and dairy products consumed in Los Angeles is greater than the volume of actual water flowing through the household taps of the city’s four million residents! After Los Angeles, the highest concentrations of “virtual river” water used in producing beef goes to Portland, Oregon; Denver; San Francisco; and Seattle.

Searching for Solutions

We were not content only to give this water crisis finer definition; we then took the next step of offering some possible solutions. Because so much of the Colorado River’s water goes to irrigating crops, our team focused on strategies for conserving water use on farms. There are many well-proven ways to reduce farm water use, but given the immense volume of water that needs to be conserved, as well as the urgent need to do so, our team focused attention on the role that voluntary, temporary fallowing of cattle-feed crops could play.

Our results were quite encouraging. We found that temporary, rotational fallowing of cattle-feed crops is affordable and can solve much, but not all, of the current water crisis. When farmers are paid to rest a portion of their alfalfa and hay fields—a practice that has already been proven to work in the Imperial and Palo Verde irrigation districts of southern California—they can boost their net incomes by “growing water” alongside their crop production.

The modest cost of compensating farmers—on average, less than $10 per person annually—could easily be added to residential and commercial water bills in cities that receive this water, in proportion to the volume of Colorado River water each customer uses. We expect the impacts on our food supply to be inconsequential, as less than 5% of the country’s alfalfa and grass hay is grown in the river basin.

Yet even if all the land devoted to growing cattle feed in the Colorado River basin were to be fallowed, it would not generate enough savings to bring water use into sustainable balance during droughts. And the water-saving burden should not fall entirely on farmers; urban water use also needs to be reduced to meet sustainable goals.

The good news is that many western cities have already cut their water use in recent decades, even while their populations and GDPs have grown rapidly. For example, Los Angeles was able to cut its use by one-fourth, even as its population grew by more than 10% and its GDP soared by more than 75%. Given the need to do more, Mayor Eric Garcetti’s “Sustainable City pLAn,” which aims to further cut water use, better utilize local supplies, and reduce by 50% the city’s dependence on water imports by 2025, is vitally important, and urgently needed.

Aggressive fallowing programs for alfalfa and grass hay will need to be a big part of an affordable solution to the West’s water-supply challenges. Now is the time for Los Angeles and other western cities to incentivize fallowing programs to their fullest potential.

Brian Richter is President of Sustainable Waters LLC, and for many years was the senior water scientist at the Nature Conservancy. Brian also teaches on sustainability and water at the University of Virginia.

Further reading: Brian D. Richter, Dominique Bartak, Peter Caldwell, Kyle Frankel Davis, Peter Debaere, Arjen Y. Hoekstra, Tianshu Li, Landon Marston, Ryan McManamay, Mesfin M. Mekonnen, Benjamin L. Ruddell, Richard R. Rushforth, and Tara J. Troy, “Water Scarcity and Fish Imperilment Driven by Beef Production,” Nature Sustainability (March 2020), https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-020-0483-z.