Part of a Special Series: Water & the Virus

The current economic crisis is ripping through the world economy. To get a sense of how the water sector is affected, we use our water blog to gain some insights from people who have their fingers on the pulse of the water sector. To be sure, the posts here are snapshots and assessments, not the final analysis of a still evolving story. We talked to Tom Rooney, CEO and President of Waterfind, a major water-trading platform in the Australia’s Murray Darling Basin (MDB).

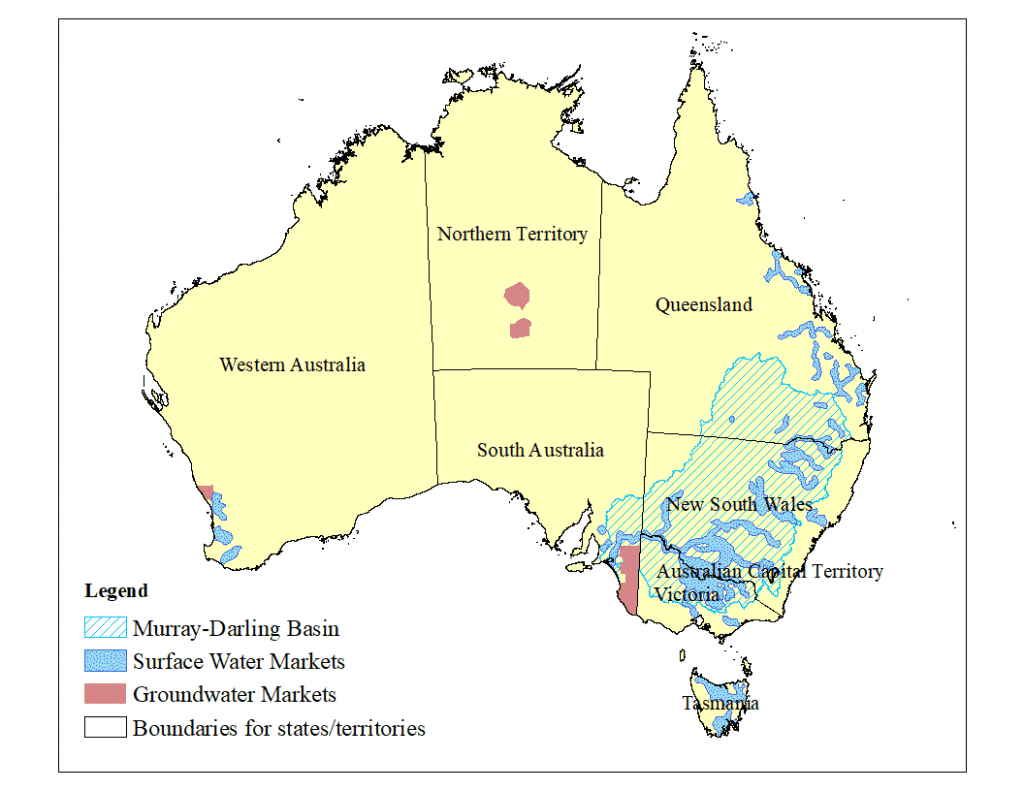

Figure 1: The Murray Darling Basin and its water markets:

Australia is a net exporter of agricultural products. The Murray Darling Basin (MDB), located in the southeast corner of the continent, is a highly diverse landscape with fascinating ecosystems and some of the greatest climatic extremes on our planet. The MDB is also Australia’s “food basket.”

The region is no stranger to water scarcity. In 1997 the MDB was hit by the Millennium Drought, which lasted more than a decade. The basin has been the focus of a national debate about water management reform for over three decades. It has the most advanced water market in the country and even in the world, and is where the majority of Australia’s water trading takes place. [i] Through a water market, water rights (the right to use water) can be bought, sold, or leased on a temporary basis. Some water rights are secure (virtually guaranteed to get water), whereas others are less so. The MDB water market functions as a cap and trade system, with an explicit limit on overall water use. From year to year, water availability can change substantially, which in turn affects the percentage of a water right that a rights holder will be able or allowed to use.

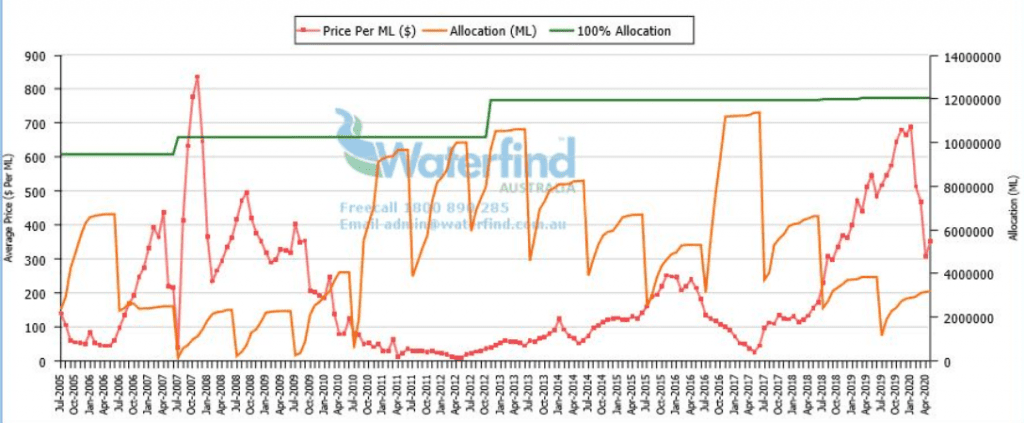

In the wake of the coronavirus we asked Tom Rooney what has been happening to water prices in the MDB. Rooney pointed to the graphs below for temporary lease prices (Figure 2) as well as for permanent sales prices (Figure 3). The price of temporary leases has been high in the last couple of years but has been declining in recent months. On average it has been at about 500 Australian dollars (320 US dollars) per megaliter (million liters), which is still under the peak of 1000 Australian dollars during the heat of the Millennium Drought. The graph shows the variations in water allocations authorized by the government at any given time (orange line)—which responds to fluctuating water availability in the system—as well as the total volume of water rights (top green line) that could be available to water users during periods with ample water supply. There tends to be a negative correlation between the water lease price and allocation. This is intuitive: the more (or less) water available, the lower (or higher) the price.

Figure 2: Water lease prices versus volume of water allocated for use since 2005

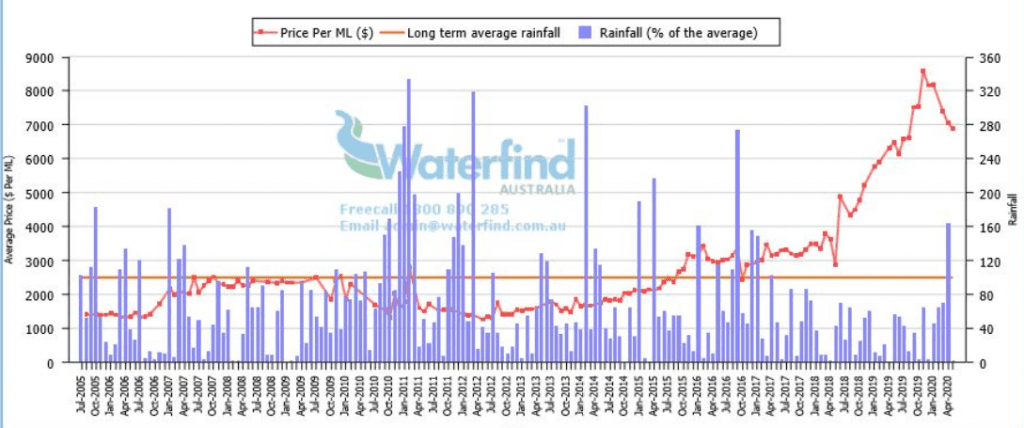

Figure 3 shows the sales price of permanent water rights, which may be indicative of longer-term expectations or trends. As one would expect, the permanent price of water is a multiple of the temporary price, just like the sales price of a house is higher than its rent. One has seen a steady climb of the sales price of permanent water rights for the last five years.

Interestingly, for the last couple of months the price for the permanent water rights has also dropped from its peak. These are fascinating graphs. Tom Rooney points out that the current water allocation is very low. Farmers are presently allowed to only use about 26 percent of their water rights, which is just a little bit higher than the worst years of the Millennium Drought.

Figure 3: Permanent Rights versus Rainfall since 2005

Now, what are we to think about the recent drop in the price of water? We focus on the permanent price as this price is likely to incorporate longer-run expectations. Yes, it is the case that the coronavirus depresses economic activity (and water demand), which should decrease prices. However, Rooney cautions against solely attributing decreasing water prices to the coronavirus. On the one hand, as one can see in Figure 3, precipitation in the MDB has increased in recent months and has been above the long-term average. More water and expectations about more available water are contributing to the decline in water’s price. In other words, nature has its role to play. In addition, the demand for permanent water rights is not solely a function of the (expected) lower water demand from farming, the most important water user in the MDB. One should also take into account the behavior of investors who hold water rights as an alternative to the traditional stocks and bonds. With the coronavirus negatively affecting the return of the more traditional assets of investors’ portfolios, some would be expected to adjust (sell) their water holdings, leading to a drop in water prices.

In the short and medium run, Rooney expects that the coronavirus will affect water permanent prices negatively. Australian Table Grape growers, for example, have recently experienced a commodity price drop due to the weakening export demand from China, and the local markets for this commodity are not profitable. With less revenue from sales, growers may decide to buy fewer permanent water rights, or they may even bring forward redevelopment plans and take patches of land that are less productive out, which is what was experienced during the Millennium Drought. In the long run, however, and barring extreme scenarios, Rooney does not expect that the negative impact of the coronavirus will outweigh the drivers of water scarcity in the region: the steadily growing demand for agricultural commodities from an ever increasing world population, and Australia’s limited water resources. The coronavirus is not going to undo the water scarcity and water stress in the region.

Rooney’s assessment that he’s not yet seeing dramatic effects on water markets due to the coronavirus is in line with the observation that the coronavirus crisis to date has affected agriculture less than, say, manufacturing. Even though there may well be bottlenecks for particular commodities, it should also be emphasized that Australia’s international trade in agricultural products is also not subject to the same uncertainty that farmers in the United States face. After the Trump administration’s aggressive use of tariffs in its trade war with China, the recent US-China trade deal, and China’s promise to buy more US agricultural products still leave ample room for the unexpected. In the meantime, however, Australia’s farmers may face the challenge of lower commodity prices (lower revenue), and still relatively high water prices (high cost).

Peter Debaere is a Professor at the Darden Business School and heads the Global Water Initiative. Brian Richter is President of Sustainable Waters LLC, and for many years was the senior water scientist at the Nature Conservancy. Brian also teaches on sustainability and water at the University of Virginia.

[i] For a more extensive discussion of water markets and water markets in Australia, see Debaere, P., “Water Markets’ Promise and Limits in a Changing World,” in Distefano, T., Water Resources and Economic Growth, Elsevier, forthcoming. Richter, B. Water Share: Using Water Markets and Impact Investment to Drive Sustainability. The Nature Conservancy, Arlington, VA (2016).