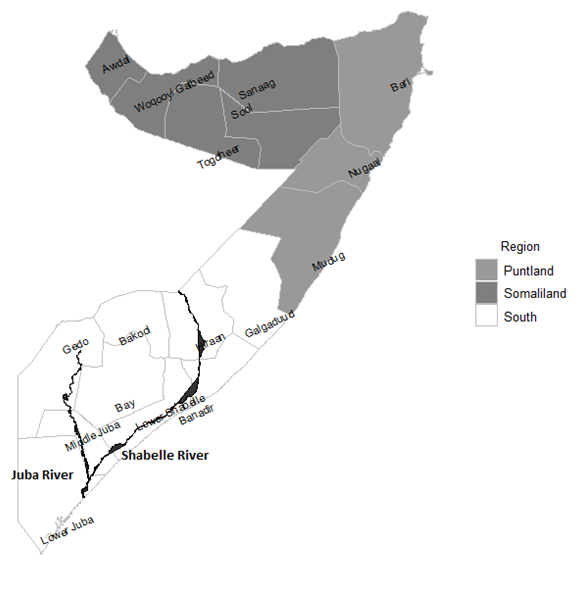

There is a long and growing literature that seeks to better understand the relationship between water (and climate change more broadly) and the prevalence of violence. The discussion has gone way beyond the occasional public statements that “future wars will be about water,” and there is a growing realization that disentangling the exact relationship between water and violence is not trivial. On February 4, Dr. Justin Schon, a postdoc in the Democratic Statecraft Lab here at the University of Virginia, gave a talk about “Water, Violence, and Internal Displacement.” Schon investigates the relationships between migration (displaced persons), violence, and water in the Federal Republic of Somalia (see map above), a country in the Horn of Africa. The presentation was part of the research series of the Quantitative Collaborative. We spoke with Schon after his talk.

As far as violence goes in Somalia, could you sketch the context for the period that you study? What are the issues? Is internal migration a big deal in Somalia?

When Siad Barre was ousted from the presidency in 1991, the Somali government collapsed. Throughout the 1990s and into the 2000s, Somalia did not have a single centralized government. Instead, its territory was ruled by a collection of warlords. This sets the stage for [terrorist group] Al Shabaab’s rise, ultimately provoking an invasion from Ethiopia at the end of 2006.

I study the time period of 2007 to 2018 in my current research. This includes a phase from 2007 to 2012, when Al Shabaab seriously threatened to seize control of the central government. Al Shabaab had been fighting Ethiopian troops from 2007 to January 2009. In 2009 and 2010, Al Shabaab came closest to taking control, and in 2011 and 2012 the Somali Transitional Federal Government finally removed the rebels from Mogadishu and secured control over key urban areas. After that, 2013–15 was relatively calm for Somalia, and the Transitional Federal Government was able to consolidate territorial control and become a permanent government. From 2016 to 2018, Al Shabaab reemerged as a potent insurgent, and Somalia’s government struggled to continue developing while fighting the insurgency.

Throughout 2007–18, there was a combination of violent and environmental threats that civilians had to navigate. Somalia has always had harsh environmental conditions, but the struggle for control of the central government as the country has attempted to rebuild from state collapse in 1991 has added an enormous amount of challenges. Estimates from the Uppsala Conflict Data Program’s violent events data show that the relatively calmest year during this period (2013) contained approximately 1,000 civilian fatalities. In most other countries, that would be cause for alarm, but for Somalia that was a peaceful year. According to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, there were 80,000 newly displaced people in 2013, as opposed to 400,000 in 2009, for instance.

Fighting during the 2007–12 phase was concentrated in Mogadishu, the capital city, so there were high levels of internal displacement from Mogadishu to rural areas. Meanwhile, a drought in 2011 aggravated insecurity. Importantly, internal displacement in 2011 went in two directions: from rural areas to Mogadishu when civilians were most concerned about drought, and from Mogadishu to rural areas when civilians were most concerned about violence. During the 2013–15 phase, Somalia was relatively peaceful, and its levels of internal displacement were very low. Then, the 2016–18 phase included a rise in violence and harsh environmental conditions. By this time, violence and harsh environmental conditions were concentrated in rural areas, so internal displacement was primarily moving from rural areas to Mogadishu.

Can you describe the water situation in Somalia? Are you worried about water scarcity, or is too much water your concern? Do you have a sense of whether and how people adapt to the water challenges of the country?

Somalia has concerns with both floods and droughts. Both can cause internal displacement: the 2011 drought is alleged to be responsible for violence and internal displacement, and in 2019, flooding was likely responsible for high levels of internal displacement. The shared timing of floods in Somalia and drought and wildfire in Australia even sparked discussion about the role of the Dipole Index in linking the climates of the Horn of Africa and Australia. Scholars such as Cindy Horst have noted that Somalis are accustomed to adapting to water fluctuations, but climate change creates fears that water fluctuations will exceed existing adaptation capacities.

In much of Somalia, people access groundwater through shallow holes, and where the infrastructure has been built, they use boreholes. There are two main rivers in Somalia—the Shabelle River and Juba River—from which people access surface water if they live sufficiently close. Unlike the United States, for instance, Somalia has very little surface water.

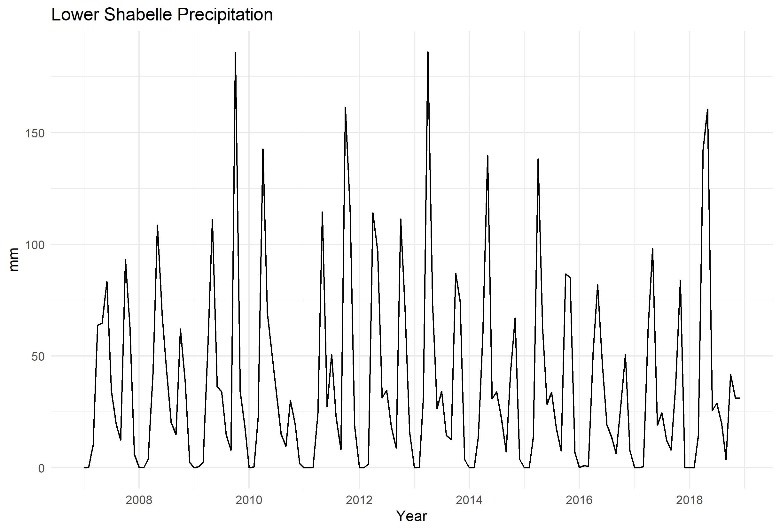

Both precipitation and surface-water fluctuations are critical to monitor in Somalia, since both dimensions of water play critical roles. My coauthors and I chose to focus our analysis on two rural regions and Banadir, the urban region that contains Mogadishu (see map above). The two rural regions, Lower Shabelle and Hiraan, contain portions of the Shabelle River. We are thereby able to examine possible differences between the effects of precipitation and surface-water fluctuations in these regions. The graph shows monthly fluctuations of precipitation in Lower Shabelle region, in order to illustrate precipitation patterns.

In your talk you emphasized that the relationship between water and violence can be relatively complex. What do you mean?

There is not a linear expectation for how water and violence are related. On the one hand, water scarcity may increase violence via competition for resources. On the other hand, excess water may increase violence via destruction of property in floods. Or excess water may help increase agricultural productivity, which could then increase the amount of resources to fight over or the amount of fuel that enables armed groups to continue fighting. There is a consensus that water and violence interact with a plethora of local, contextual factors, but that does not help us generate a single straightforward set of expectations.

Furthermore, civilians can and do respond to water fluctuations with wide repertoires of adaptation strategies. It is not a given that too much or too little water will necessarily spark violence or internal displacement. This means that if there is an effect of water fluctuations on violence and displacement, that effect could be delayed or manifest differently at different points in time.

This complexity makes many traditional methods of quantitative analysis extremely difficult for reliable hypothesis testing. For time series analysis specifically, standard assumptions of stationarity (constant mean and variance for the time series) are unreasonable. Varying lags in responses also make it difficult to apply many methods.

We are therefore working with wavelet analysis, a complex form of time series analysis that allows the user to analyze non-stationary time series. Our analysis is in its early stages, so we hope that readers stay tuned for progress on this work.

As far as violence goes in Somalia, could you sketch the context for the period that you study? What are the issues? Is internal migration a big deal in Somalia?

When Siad Barre was ousted from the presidency in 1991, the Somali government collapsed. Throughout the 1990s and into the 2000s, Somalia did not have a single centralized government. Instead, its territory was ruled by a collection of warlords. This sets the stage for [terrorist group] Al Shabaab’s rise, ultimately provoking an invasion from Ethiopia at the end of 2006. Somalia has always had harsh environmental conditions, but the struggle for control of the central government as the country has attempted to rebuild from state collapse in 1991 added an enormous amount of challenges.

I study the time period of 2007 to 2018 in my current research. Throughout this period, civilians had to navigate a combination of violent and environmental threats. This includes a phase from 2007 to 2012, when Al Shabaab seriously threatened to seize control of the central government. Al Shabaab had been fighting Ethiopian troops from 2007 to January 2009, and in 2009–10, the group came closest to taking control. Fighting during the 2007–12 phase was concentrated in Mogadishu, the capital city, so there were high levels of internal displacement from Mogadishu to rural areas. Meanwhile, a drought in 2011 aggravated insecurity. Importantly, internal displacement in 2011 went in two directions: from rural areas to Mogadishu when civilians were most concerned about drought, and from Mogadishu to rural areas when civilians were most concerned about violence.

In 2011 and 2012 the Somali Transitional Federal Government finally removed the rebels from Mogadishu and secured control over key urban areas. After that, from 2013 to 2015, the Transitional Federal Government was able to consolidate territorial control and become a permanent government. During this phase, Somalia was relatively peaceful, and its levels of internal displacement were very low. Estimates from the Uppsala Conflict Data Program’s violent events data show that 2013 was the calmest year during this period, with approximately 1,000 civilian fatalities. In most other countries, that would be cause for alarm, but for Somalia that was a peaceful year. According to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, there were 80,000 newly displaced people in 2013, as opposed to 400,000 in 2009, for instance.

However, from 2016 to 2018, Al Shabaab reemerged as a potent insurgent, and Somalia’s government struggled to continue developing while fighting the insurgency. The 2016–18 phase also included harsh environmental conditions. Both violence and harsh environmental conditions were concentrated in rural areas, so internal displacement was primarily moving from rural areas to Mogadishu.