Daryl Vigil visited the University of Virginia on April 5 and 6. At the Darden School of Business he talked about Governance and Water Scarcity in the Colorado Basin: What Role for Indian Tribes? Daryl Vigil is the Water Administrator for the Jicarilla Apache Nation and the former Chairman of the Colorado River Basin Ten Tribes Partnership. Vigil contextualized the water issues in the Colorado River Basin, while at the same time arguing that 2022 presents an extraordinary opportunity to change the governance of the river. After having been ignored for over 100 years in water negotiations, there now appears to be an opportunity for Native Americans to gain a seat at the table.

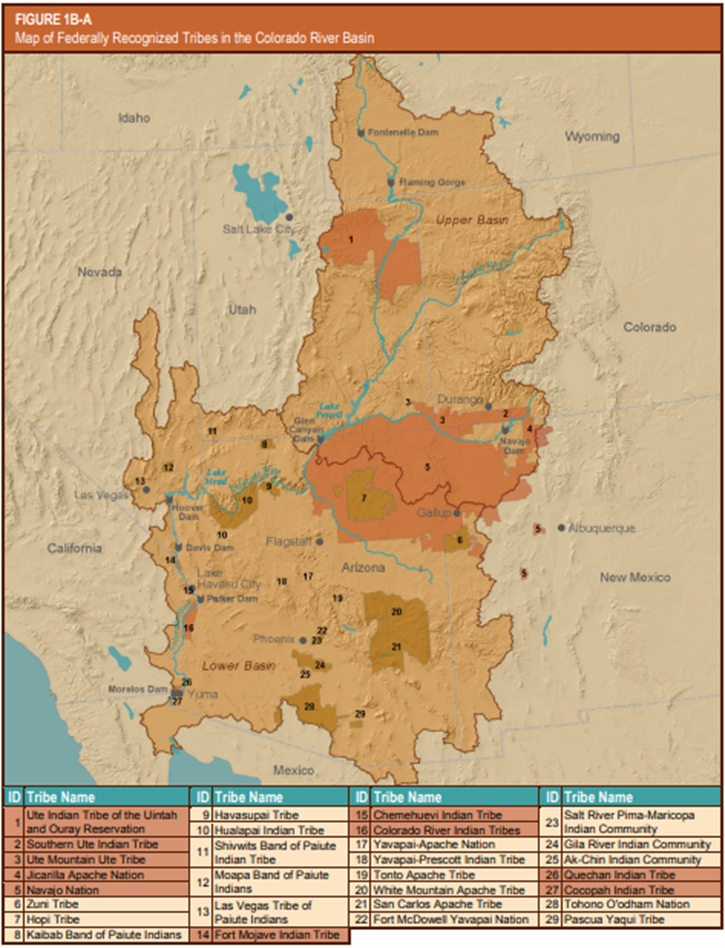

Vigil positions the water challenges Native Americans face within the complex water system of the Colorado River. Some 41 million people – including 30 Native American tribes — depend on the river that flows in two countries (the United States and Mexico) and seven American states (Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, New Mexico, Arizona, California and Nevada). The Colorado’s water has long been over-allocated and over-used, a condition that has rapidly worsened while the basin has been experiencing a “megadrought” for the past 22 years. In three out of four years during this period, water consumption has exceeded the volume of water flowing in the river. Not surprisingly, the water levels of America’s two largest reservoirs — Lake Powell and Lake Mead, formed by Glen Canyon Dam and Hoover Dam, respectively — are critically low.

To understand the water allocation along the river, Vigil points to the Colorado River Compact that the seven US states agreed upon in 1922. This federally sanctioned deal guaranteed the Lower Colorado River users 7.5 million acre feet of water, and allocated an equal volume to users in Upper Colorado River 7.5 million, or a percent of whatever is left after 7.5 million acre feet are delivered downstream. The Upper Colorado River Commission governs the Upper Basin, and the US Bureau of Reclamation governs the Lower Basin. The Compact paved the way for critical water infrastructure investments to manage the water, including the construction of Glen Canyon Dam and Hoover Dam. Importantly, Native Americans were not part of the 1922 agreement and had no say in how the water they had relied on for thousands of years was managed. As a matter of fact, many were not recognized as US citizens at the time or, as in the case of Vigil’s tribe, had not yet formally adopted their constitutions, and were living at subsistence levels on lands removed from their original hunting and gathering grounds.

The water law of “prior appropriation” governs water use in the West. Those who have the oldest rights have the strongest claim: “First in right, first in use.” Vigil emphasizes that the Native tribes (currently some half a million people in the basin) have now gained historic rights to the water that predate the River Compact, which are among their most valuable assets. These very senior claims amount to a quarter of the river, and this share is expected to increase as the available water is decreasing with climate change. However, not all tribal rights have been settled since not all have gone through a lengthy adjudication process that can take years if not decades. For example, Vigil’s tribe, the Jicarilla Apache Nation, settled its rights only in 1992. The Jicarilla has its reservation in the Upper Colorado River and their rights amount to 11 percent of the Upper Colorado River. Vigil underscores that due to a lack of funding and an underdeveloped infrastructure, Native tribes do not currently use all of their adjudicated water. As a matter of fact, access to safe drinking water is an issue. Native American households are 19 times more likely to lack piped water services than white households, and some still depend on water tankers for their water.

There is a historic opportunity, says Vigil, to rewrite the governance of the Colorado River. In 2007, a suite of Interim Guidelines were negotiated that govern water use and the operation of the reservoirs under drought conditions. These rules are meant to reduce the risk of water shortages and are supposed to keep the storage of water in Lake Mead and Lake Powell in balance. After 15 years, those Guidelines are about to be renegotiated and renewed in 2026. Vigil has been singularly focused on making sure that Native Americans this time have a chair at the negotiating table, ss sovereign entities, on par with the states. Achieving this also involves bringing the tribes together. The Ten Tribes Initiative, for example, has produced a report that lays out their thinking. Educating people about the cause is equally important. Vigil sees the irony that Native Americans who have been present in the basin for thousands of years have to make people aware of their plight. For Vigil the water renegotiations are a core part of a larger cause. Living conditions on the reservations are hard, often with very limited opportunities. In his words: “We cannot move forward if the past is not reconciled.”

While settling water rights, and gaining a seat at the table are essential, it is of equal importance to the Native tribes to put their water rights to beneficial use, or to lease them if not needed on reservations. For example, Vigil’s tribe historically received valuable funds from leasing water to a downstream power plant, but when the power plant was decommissioned by the state (without consulting the tribes), those funds dried up. Finding other entities to lease their water to is not always easy. The states do not, in most instances, allow for leases that cross state boundaries. Vigil underscores how his tribe has recently negotiated a deal between the state and his tribe, from sovereign to sovereign, that now channels the water to a “strategic water reserve” in New Mexico; this strategic reserve is intended to aid the state in meeting their inter-state compact commitments. Such water deals are essential, as in many instances, water not claimed may just flow downstream without any remuneration.

Here is a link to the Ten Tribes Partnership Water Study.