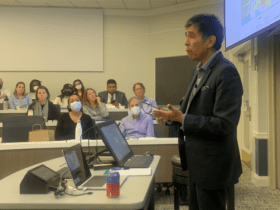

Dr. Marama Muru-Lanning from the University of Auckland, New Zealand, is the first Māori Anthropologist to be awarded a PhD in anthropology since Māori Studies separated from Anthropology in 1991. Marama Muru-Lanning heads the James Henare Research Center at the University of Auckland. She is the author of Tupuna Awa: People and Politics of the Waikato River. The Waikato River is a 425-kilometer long river close to Auckland, along which her people have always lived and whose rights to the river had been denied following the confiscation of their lands in the 1860s. Marama Muru-Lanning participated in a panel at the University of Virginia about indigenous ecologies. We talked to her about how the particular relationships with water have evolved for various Māori groups in New Zealand, how their relations to the river have been essential to Māori legitimating their unique identity as a people, having lost their land, and how the new settlement with the Crown is changing this relationship.

Who are the Māori people?

Māori are the indigenous people of Aotearoa-New Zealand. Ancestors of Māori originated from eastern Polynesia and arrived in Aotearoa in several waves of canoe voyages between 1250 and 1300. Today Māori make up approximately 14.9% of Aoteroa’s population (New Zealand Census 2013) and are the second-largest ethnic group in the country, after European New Zealanders (Pākehā). One of the most useful texts available dealing with the question of who Māori are is Ranginui Walker’s Struggle without End. Walker’s work provides a uniquely Māori view, not only of the socio-political events of the past two centuries in Aotearoa but beyond to the very origins of Māori people.

What has traditionally been the relationship with water?

I grew up at Tūrangawaewae Marae on the banks of the Waikato River. I know about its flooding and currents, it’s high and low water lines. I know about the safe places for swimming, and the least dangerous places to jump into it from the bridges. I remember the mists and living in fog, days of being cold to the bone. I know the smell of the river. I crossed it every day to get to school. The river is my ancestor, my Tupuna Awa.

For hapū (clans) and iwi of the lands that border its 425-kilometre length, the Waikato River is an ancestor, a taonga (treasure) and a source of mauri (life-essence), lying at the heart of identity and chiefly power.[1]

In light of the early expropriation of Māori lands, you have argued that the link to the river was all the more important for Māori identity. In this context, what is the Wakaito deed of settlement? And what does it mean for the evolving relationship of the Māori and the Wakaito River?

The Waikato River claim resulted from the Colonial Government’s confiscation of Waikato lands in the 1860s which denied the rights and interests of Waikato Māori in the Waikato River. The river claim was excluded from Waikato iwi’s (tribal nation) 1995 land settlement and was set aside for future negotiation. Representatives of the New Zealand Crown and the newly configured Waikato-Tainui iwi signed a Deed of Settlement for the Waikato River in August 2008. This agreement recognised in legal terms the significance of the Waikato River to Waikato-Tainui Māori. It was also the commitment by the New Zealand Crown to Waikato-Tainui Māori to co-manage the Waikato River. Importantly the deed of settlement created a $210 million clean-up fund.

However, under the direction of a newly elected Government in 2009, the Crown was forced to review aspects of the co-management arrangement for the Waikato River and with the agreement of Waikato-Tainui, appointed an advisory panel to do so. This led to a revised deed, streamlining the co-governance arrangement that created a single co-governance entity, named the Waikato River Authority (WRA). While the previous arrangement provided for six statutory boards the WRA is made up of equal numbers of Crown and iwi appointed members, including representatives from other iwi with rights and interests in the river. The WRA is responsible for monitoring the implementation of a direction setting document known as Te Ture Whaimana (Vision Strategy).

Te Ture Whaimana informs the Waikato Regional Policy Statement and gives effect through the plans administered by regional and territorial authorities along the river. Te Ture Whaimana is the primary policy for the Waikato River and focuses on restoring and protecting the health and wellbeing of the river for future generations. Vital to Te Ture Whaimana success is the $210 million dollar clean-up fund.

Overall the Waikato River deed of settlement provides for joint management agreements between Waikato-Tainui and local authorities; participation in river-related resource consent decision-making; recognition of a Waikato-Tainui environmental plan; provision for regulations relating to fisheries and other matters managed under conservation legislation and an integrated river management plan.

[1] To attain a comprehensive understanding of the multiple relationships that Māori have with water see also Harmsworth and Awatere’s Indigenous Māori Knowledge and Perspectives of Ecosystems and Chapter nine in Anne Salmond’s The Tears of Rangi: Experiments Across the Worlds.