On October 26, the Global Water Initiative held its first Graduate Water Colloquium. It brought together over 40 graduate students and faculty who work on water-related issues across the University of Virginia. Nine UVA students in disciplines ranging from engineering to economics to architecture presented their ongoing research on water, receiving constructive feedback from peers and colleagues. The Global Water Initiative also awarded its first Global Water Initiative Graduate Prize. The selection committee of faculty and graduate students, led by Professor Teresa Culver from Engineering, unanimously selected Courtney Hill. Courtney is a PhD student in engineering who works with Professor Jim Smith at UVA. At the colloquium Courtney presented “Technological Field Performance of a New Point-of-Use Water Treatment Technology in a Randomized Control Trial in Limpopo, South Africa.” We talked with her.

What is the new point-of-use water treatment technology you are studying?

The MadiDrop is a microporous, water-permeable ceramic tablet infused with microscopic silver clusters that was developed at the University of Virginia. When placed in a 20-liter storage container filled with water, the tablet continually releases low levels of silver ions, killing harmful pathogens in water for up to 12 months. The consumers simply place the MadiDrop in untreated water when they go to sleep, and when they wake up, the water is ready to drink.

The MadiDrop is a point-of-use water treatment technology, an inexpensive, effective solution to reduce waterborne disease as it allows households to treat water in the home shortly before they drink it. Researchers have shown that point-of-use treatments are more effective than state- or community-run water systems in low-resource settings. Compared to other common water treatment approaches and products, the MadiDrop delivers effective and exceptional safe water results. (See table below to compare different point-of-use water treatment methods, including the MadiDrop).

Silver ions disinfect many different pathogenic waterborne bacteria, including Escherichia coli, Vibrio cholera, Salmonella, and Shigella. Viruses such as poliovirus and norovirus, as well as the protozoa Cryptosporidium parvum and Giardia lamblia, can also be inactivated by silver. Unlike other metals such as lead and mercury, silver is not toxic to humans. It is not known to cause cancer, reproductive or neurological damage, or other chronic adverse effects. Both the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) recommend a maximum silver concentration of 0.1 mg/L in drinking water. The MadiDrop produces ionic silver levels sufficient to disinfect or inactivate waterborne pathogens while remaining below the daily maximum recommended concentration.

Why is a randomized controlled experiment in order? And how is the experiment set up?

MadiDrops have been shown to be socially acceptable and to effectively disinfect household water in field studies. However, how these improvements in water quality translate to health improvements is still being examined by researchers. To better understand this relationship, I collaborated with public health and environmental science faculty at UVA and the University of Venda in South Africa to conduct a randomized controlled trial. We were looking at the impact of access to point-of-use water treatment devices on early childhood growth stunting. A randomized controlled trial is a type of clinical trial that compares two or more groups of people who are randomly selected to either receive or not receive a treatment. Randomly assigning people to each group via a computer program is the best way to ensure that the results are not biased by the way participants in each group are selected.

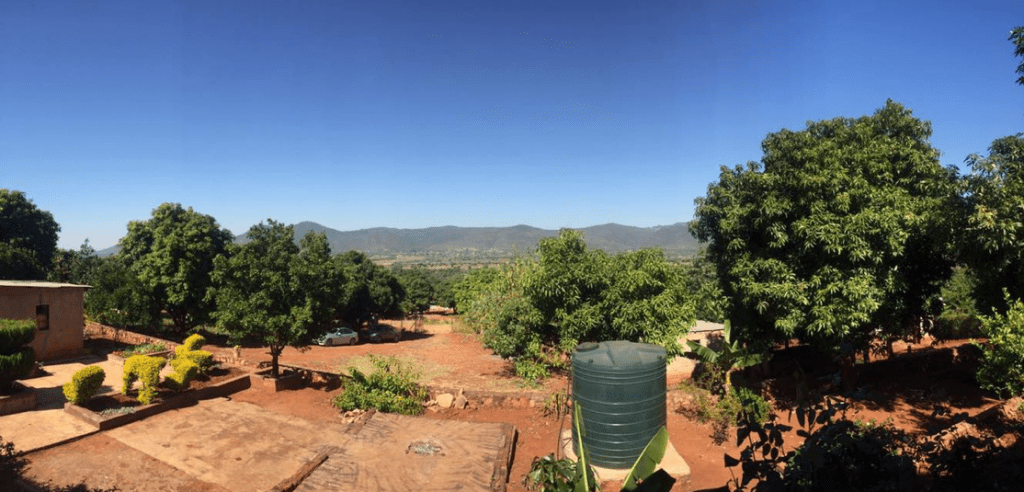

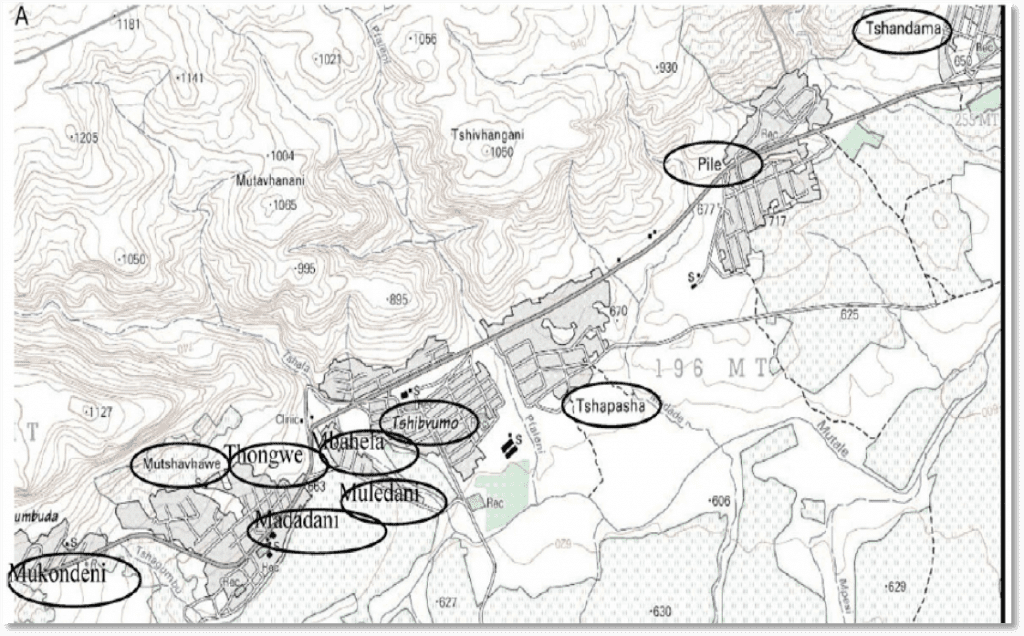

For two years, our study followed 400 households in rural South Africa that were randomly selected to receive at no cost one of the following: a MadiDrop, a ceramic water filter, a safe water storage container (a plastic bucket with a spigot for water covered by a plastic lid), or no intervention. For the study, we measured the height and weight of every child in each household and the prevalence of pathogens in the stool of the youngest child at enrollment. I also initiated a collaboration with colleagues from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) to use their product, a SmartspoutTM spigot, to measure the frequency at which households used each given intervention. While health outcomes were being measured by South African partners, a team from UVA measured water quality of both untreated water in the home and treated water from homes with MadiDrops, ceramic water filters, and safe water storage containers to make sure that they were performing as we had seen them perform in previous field studies. We worked in different villages in the province of Limpopo. (See maps below.)

With a study like this, there were so many logistical challenges that had to be coordinated year-round in order to get the data we needed. Every time a local field worker visited one of the participants’ homes, he or she turned in a form to the data office for that visit. Each form was then double-entered into a database. Often during these visits, the field worker also collected a stool sample from the youngest child in the home, which required an additional form. Over two years, this amounted to thousands of forms and stool samples, and keeping track of everything to make conclusions was quite a task! However, this study was a joy to work on. I’ve visited South Africa six times for the project and gained meaningful friendships with collaborators from the University of Venda. I am so grateful that I was able to spend graduate school working on this project.

So, what did you find? And what further questions/issues need to be investigated?

The final household visit for the study happened just last month, so we are still processing the health data to draw conclusions. However, we have completed all of the water quality tests and got some important results. Over the two years that we monitored these interventions in homes, both the MadiDrop and the ceramic water filters significantly reduced total coliform bacteria, a common marker of water quality. We were also able to determine that silver in ceramic filters plays a big role in disinfection and that a safe water storage container alone doesn’t have much of an effect on preventing contamination in water.

Going forward, more work needs to be done to understand the use of these devices and how to optimize water treatment devices for consumers. People overreport when you ask them how often they use something that you gave them—this was made clear after we installed SmartspoutsTM in the spigots of homes with MadiDrops and ceramic water filters. More research also needs to be done to understand what other benefits interventions like the MadiDrop can have. For example, the device has the potential to kill mosquito larvae and potentially prevent malaria transmission in the home.