Most major aquifers in the dry parts of the world are being depleted rapidly, as more water is being extracted than can be naturally replenished. A third of the world’s biggest groundwater systems are already in distress.[1]

In India, one of the most water-challenged countries in the world, 54% of groundwater wells are decreasing.[2] A recent report[3] suggests that 21 major cities in India (Delhi, Bengaluru, Chennai, Hyderabad, and others) are moving toward zero groundwater levels by 2020, which will affect water access for 100 million people. With the national supply of water predicted to fall 50% below demand by 2030,[4] the availability of water in the future can only worsen, posing a serious threat to the people relying on groundwater.

The impact of water scarcity on food security and poverty has already been documented.[5] However, evidence of gender-based distributional effects of water scarcity is relatively limited. It is well documented that women and girls bear the overwhelming burden of collecting water when their households do not have access to piped water.[6] During negative shock episodes, the wells dry up, and the distance to and congestion around surviving water sources increases, see Figure above from small town in Rajasthan. Therefore, women have to go farther to collect water, and in order to avoid congestion they often travel in the early morning when it is dark, making them vulnerable to violent attacks including sexual abuse and rape. While there has been some suggestive evidence by qualitative fieldwork-based reports and media accounts that groundwater scarcity increases violence against women, causal evidence is nonexistent. In our recent working paper “Water in Scarcity, Women in Peril,” we address this paucity of evidence by isolating the causal effects of groundwater scarcity in India on violence against women, focusing on rape.

We use three main sources of data for our empirical analysis. We collect district-wide groundwater level data from the Indian Central Groundwater Board. District-wide crime data come from the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB). We limit our analysis to the period of 2002–7. We also use two waves (2004–5 and 2011–12) of the Indian Human Development Survey (IHDS) to provide evidence supporting the potential mechanism. In addition, we collect district-level demographic data from the 2001 population census of India.

We rely on the exogenous nature of groundwater shocks for our identification. We argue that, controlling for year and district fixed effects as well as annual rainfall, annual groundwater shocks are largely exogenous. We strengthen our argument by providing insights from geology that explain why annual fluctuations in subsurface water are largely geogenic, and hence exogenous, so that rural households are unable to predict a year’s groundwater yield. Field studies corroborate the presence of the geological phenomenon that makes groundwater recharge exogenous and difficult to predict.

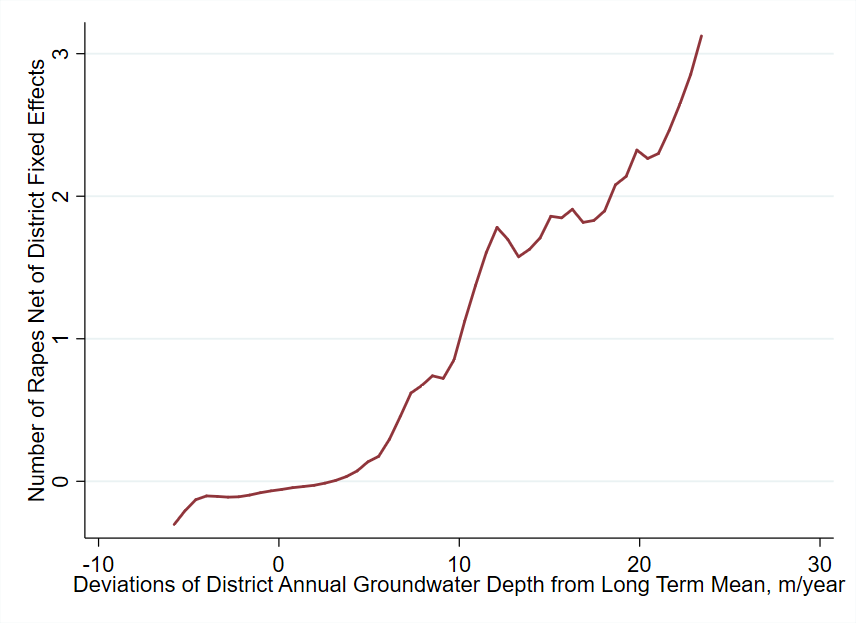

We find that negative shocks, as measured by deviations of groundwater level below its long-run mean, cause an increase in the number of reported rapes. (If the deviation from the long-run mean is positive, it implies that groundwater levels have fallen further. Hence, positive deviations indicate negative shocks; see Figure below.) We observe a 2.1% increase in reported rapes due to negative groundwater shocks. Our results are robust to a variety of specifications and different controls, such as local economic conditions proxied by trends in nighttime average luminosity and poverty, rainfall, temperature, and district-specific time trends. To rule out the effects on contemporaneous shocks of the previous year’s irrigation and extraction, we also control for the lags and leads of the shocks and show that the results remain stable.

Using the nationally representative IHDS data, we provide evidence suggesting that negative groundwater shocks might increase violence against women and girls by increasing the distance they have to travel to collect water. We establish the chain of mechanism in three steps. First, we show that, during the negative shock episodes, households relying mostly on groundwater have to travel farther to fetch water. Second, we show that women and girls have to disproportionately bear the burden of traveling farther to collect water. Finally, we show that the incidence of rapes increases when households relying on groundwater experience negative groundwater shocks.

Our results have significant policy implications. A dire forecast of groundwater availability in the near future in India means women have to walk longer distances to collect water, making them increasingly susceptible to violence. Policy interventions aimed at mediating negative water shocks by the conservation of groundwater can go a long way toward improving women’s welfare. Additionally, improvement in local water infrastructure in rural areas can enhance women’s safety by making water locally available.

Sheetal Sekhri is Associate Professor of Economics at the University of Virginia. Her research focuses on development economics as well as on water. Md Amzad Hossain is a Research Assistant at the University of Virginia.

[1] Alexandra S. Richey, Brian F. Thomas, Min-Hui Lo, John T. Reager, James S. Famiglietti, Katalyn Voss, Sean Swenson, and Matthew Rodell, “Quantifying Renewable Groundwater Stress with GRACE,” Water Resources Research 51, no. 7 (July 2015): 5,217–38.

[2] Tien Shiao, Andrew Maddocks, Chris Carson, and Emma Loizeaux, “3 Maps Explain India’s Growing Water Risks,” World Resources Institute, February 26, 2015, https://www.wri.org/blog/2015/02/3-maps-explain-india-s-growing-water-risks (accessed Sept. 4, 2019).

[3] Mahreen Matto, “India’s Water Crisis: The Clock Is Ticking,” DownToEarth (blog), July 1, 2019, https://www.downtoearth.org.in/blog/water/india-s-water-crisis-the-clock-is-ticking-65217 (accessed Sept. 4, 2019).

[4] Lee Addams, Giulio Boccaletti, Mike Kerlin, and Martin Stuchtey, “Charting Our Water Future: Economic Frameworks to Inform Decision-Making,” 2030 Water Resources Group, 2009, https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/dotcom/client_service/sustainability/pdfs/charting%20our%20water%20future/charting_our_water_future_full_report_.ashx (accessed Sept. 9, 2019).

[5] See for example, Sheetal Sekhri, “Wells, Water, and Welfare: The Impact of Access to Groundwater on Rural Poverty and Conflict,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 6, no. 3 (2014): 76–102.

[6] For instance, in Somalia, 66.4% of the water carriers for the 71% of households that do not have access to clean water are women, whereas the corresponding number for Laos is 83.4%. In Malawi, 87.2% of water carriers are women, and in Bangladesh this number is 88.8%. See Susan B. Sorenson, Christiaan Morssink, and Paola Abril Campos, “Safe Access to Safe Water in Low Income Countries: Water Fetching in Current Times,” Social Science & Medicine 72, no. 9 (May 2011): 1,522–26.