Many areas of the world are grappling with water scarcity due to changing environmental conditions (droughts, climate change, etc.) and increased consumption, as well as poor water quality related to changing demands, pollution and lacking infrastructure. Current models forecast water stress in many areas of the world in the years ahead while the United Nations has declared water and sanitation a human right. This confluence of events is putting pressure on governments, which typically provide these services, to find funding. User fees and taxes have been traditional funding mechanisms. However, user fees are regressive and typically don’t cover the cost of services, and the allocation of tax revenue is subject to politics and an annual budget process. To meet the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal of access to safe and affordable drinking water by 2030, researchers estimate that we need $1.7 trillion (Hutton and Varughese, 2016). If we want water to be a human right, we must be open, but not complacent, to private capital.

Large investors (e.g. banks, pensions and high-net-worth individuals) can invest directly in “water assets” or through venture capital, private equity and hedge funds, which require a significant minimum investment to be locked up in the fund for up to ten years. “Water assets” can include land with water rights, utilities, infrastructure projects, and technology start-ups which focus on water quality or efficiency. Several banks have referred to water as the next oil. However, the investment case in water must be coupled with the ethics case of a declared human right under the control of a few.

What about the rest of us. How can we invest in water?

A favorite investment option for many small investors is a mutual fund or an exchange traded fund (ETF). Both are professionally managed investment vehicles that provide investors diversification and liquidity by pooling the money of many together into a portfolio of assets. So what is the mutual fund and ETF landscape for water?

Morningstar currently reports 126 water-focused mutual funds and 11 water-focused ETFs worldwide. All of the ETFs and 112 of the 126 mutual funds are available to small investors. Of the 112 mutual funds 82 invest in equities. Of those equity funds, almost 80% invest in global equities. The majority of these equity funds are available to investors across Europe (25 funds), Japan (16 funds) or Netherlands (12 funds).

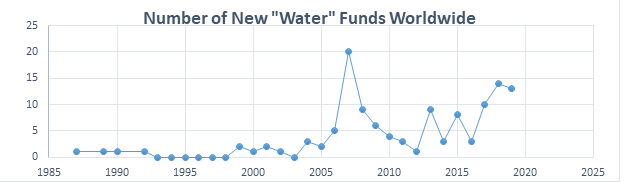

The chart below shows the worldwide inception of these current water funds over time. New funds for sale in Japan and across Europe created the large spike in 2007 while new funds for sale in the Netherlands led to jumps in 2013 and 2015. The last three years have seen a continued increase in introduction of funds across the world.

In the US, only three mutual funds and five ETFs are sold to small investors according to Morningstar. Of these eight options in the US, seven invest in equities and are thematic water-focused funds. The one fixed income fund, which was established most recently (November 2018), invests in green bonds that could be water related.

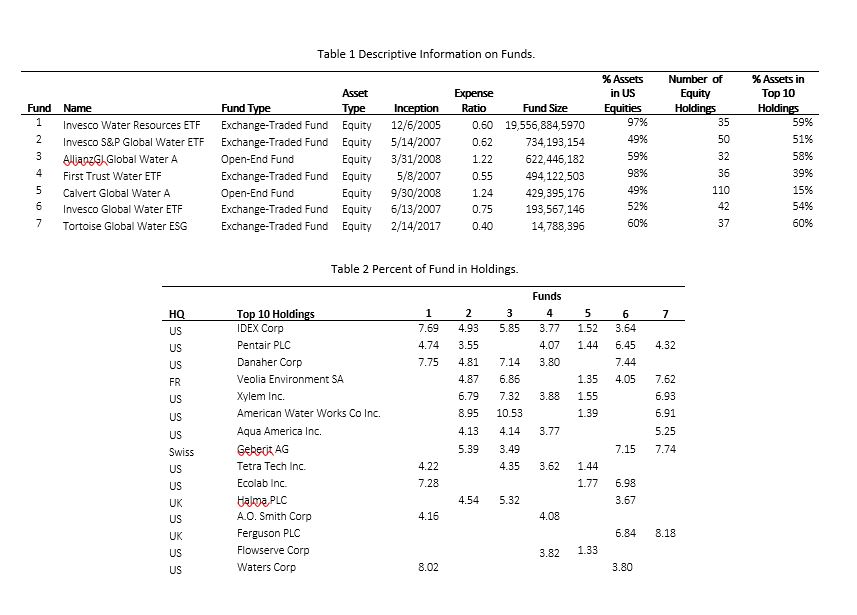

Table 1 shows the seven equity funds. By far, the largest fund is the Invesco Water Resources Fund ETF. At $19.6 billion it is the only fund with over $1 billion and is 27 times the next largest fund. Not surprisingly, the two actively-managed, open-end equity funds have significantly higher expense ratios than the passively-managed ETFs. All the equity funds, but Calvert Global Water, hold at least a majority of their assets in US equities, hold 50 or less companies, and allocate a majority of their assets to their top 10 holdings. Table 2 provides the top 10 holdings from the seven equity funds that overlap. The variety of companies in a water fund is evident by looking at the five companies held by five of the seven funds. IDEX Corp. and Danaher Corp. are US companies with up to 12% of their revenues from their water platforms while Pentiar PLC and Xylem Inc. focus exclusively on water solutions and Veolia manages utilities including water and waste management services. We also see that more than 70% of the companies are US based. This heavy emphasis on US companies is not because these are funds for US . An analysis of other large funds based in Luxembourg and available to others markets have similar holdings and emphasis on US public companies.

So if these funds do well you benefit, but does it help reduce water scarcity? Not directly. The fund is simply buying shares from another investors through “secondary” trading. The companies never see the cash that you invest through a fund or buying the shares directly on an exchange. A benefit may arise if demand for the companies increases enough to raise stock prices, and the companies need to raise additional capital for investment opportunities that reduce water scarcity. If the managers receive compensation in the form of stock, an increase in the stock price also rewards managers for reducing water scarcity, encouraging them to continue their efforts. However, Danaher and IDEX only have a small percentage of the company driven by water and many factors affect a company’s stock price. As an investor in a mutual fund, you must rely on the manager of the fund to monitor and communicate with the company regarding its strategic direction for reducing water scarcity.

So while you can make a return investing in mutual funds and ETFs focused on water, are there more direct ways for small investors to fund efforts to reduce water scarcity?

Yes – but that is a story for another day.

Mary Margaret Frank is a Professor of Business Administration at the Darden Business School, and an expert on Private-Public Partnerships.

Hutton, Guy; Varughese, Mili Chachyamma. 2016. The costs of meeting the 2030 sustainable development goal targets on drinking water sanitation, and hygiene (English). Water and Sanitation Program technical paper. Washington, D.C.:World Bank Group.