The Blue Nile Health Project (BNHP) and the International Drinking Water Supply and Sanitation Decade (IDWSSD, the Water Decade) are examples of extraordinary cooperation and coordination. The Water Decade marked the beginning of the global effort to provide clean drinking water and adequate sanitation for all. The BNHP demonstrated that with adequate financing, staffing, interdisciplinary cooperation, and community buy-in, extraordinary results can be achieved. It also underscored that success depends on sustained, long-term investments.

The 1970s and ’80s were arguably the most important time in the history of water development since the sanitary revolution in the middle of the 19th century. The water infrastructure established in many cities in Europe and America was never built in much of the rest of the world. That began to change during the Second Sanitary Revolution of the ’70s and ’80s. The Second Sanitary Revolution grew out of environmental health, a field expanded in the post–World War II period; drawing on the best aspects of 19th-century sanitary science, environmental health considered sanitation and clean water essential for human and economic flourishing. The Second Sanitary Revolution reached its apex in the 1970s and ’80s. Beginning in the early 1970s, the major international organizations, like the World Bank, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), and the World Health Organization (WHO), among others, began to take a sustained interest in water and sanitation.

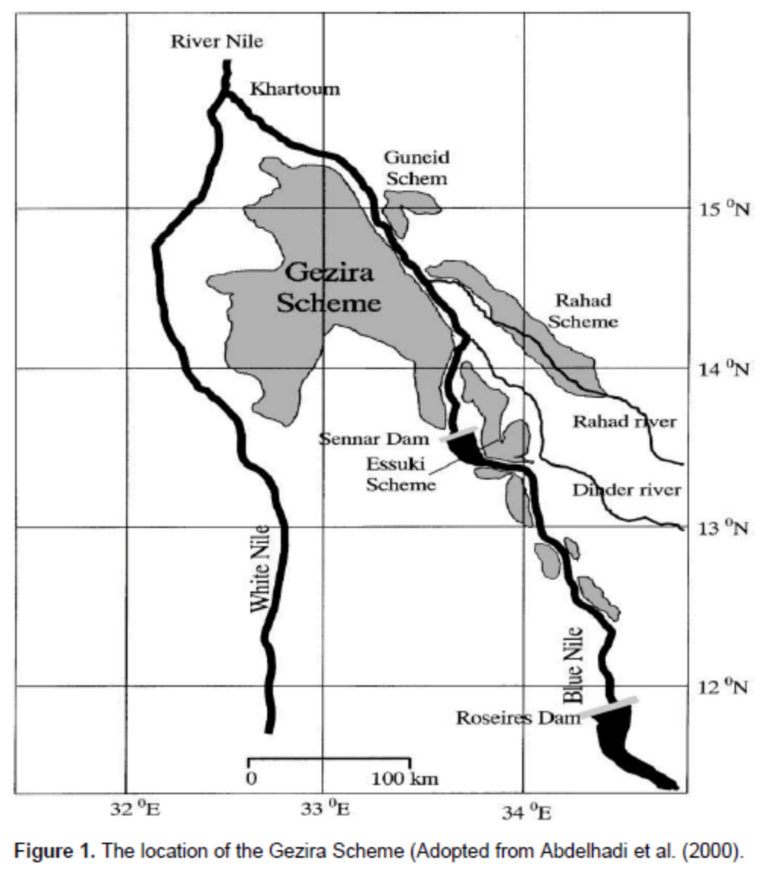

Two massive and wildly ambitious projects showed what was possible. The Water Decade and the BNHP aimed for nothing less than a total overhaul of the way water was developed. The WHO considered the Water Decade a key component of its campaign to achieve health for all, and a “development in the spirit of social justice.”[i] The architects of the BNHP hoped to foster a rethinking of irrigation projects so that they would not have such adverse effects on health. For decades, many had realized that irrigation projects were incubators of disease—especially in places prone to water-related diseases like malaria and schistosomiasis. Water was a bedrock of economic development, but when, for example, malaria and schistosomiasis were left to fester on the Gezira Scheme in Sudan, people simply could not thrive. The BNHP aimed to change that.

The World Bank began the 1970s recognizing that “there is clearly a larger role” for it to play in water supply and sewerage. The Bank had been active in developing irrigation projects, but wanted to move beyond them. Its newfound commitment showed: in 1971, the Bank spent more on water and sewer projects—$189 million—than in all previous years combined. That same year, the WHO and the Bank entered into a formal agreement: they would combine their respective expertise and work together on the problem of water. By the middle of the 1970s, more was being done to develop water and sanitation in the developing world than had been done at any other time—UNICEF installed thousands of pumps all over rural India; the Bank and the WHO helped to set up local water boards in places like urban Uttar Pradesh; and the Bank and the WHO began to take seriously the problems of access to water in Africa—but by decade’s end, many believed that not enough was being done to meet the world’s drinking water and sanitation needs.

And so, in 1977, the UN convened the first global water conference at Mar del Plata, Argentina. Some of the resolutions agreed to at the meeting were radical—they contained ideas few had broached, much less agreed to at a global level. For example, the participants resolved that “All peoples, whatever their stage of development and their social and economic conditions, have the right to have access to drinking water in quantities and of a quality equal to their basic needs.”[ii] In a section on “Water Policies in Occupied Territories,” the participants took a firm stand against those in power who would limit access to water to those without power, “Noting with great concern the illegitimate exploitation of the water resources of the peoples subject to colonialism, alien domination, racial discrimination and apartheid, to the detriment of the indigenous peoples.”

Out of that meeting, and based on expertise gained over the preceding half decade, the Bank, the WHO, the UNDP, and delegates from the 116 states present committed themselves to launching, funding, and carrying out the International Drinking Water Supply and Sanitation Decade. The Decade’s goal was ambitious: provide 2 billion people with clean water and sanitation. When thinking about the importance of the Decade and what it might achieve, a panel of experts at the WHO and the Bank wrote in 1979: “Few development projects have greater potential for directly benefiting the health and social and economic well-being of mankind than water supply and sanitation services.”[iii] Dr. Peter Lowes, the WHO/UNDP coordinator for the Water Decade, made clear that the Decade sought to accomplish globally what had been accomplished in England 130 years previously.

This kind of ambitious thinking was countered by those who argued that water supply and sanitation were too expensive and that other kinds of interventions would do more, at lower cost, to improve health—or at least to cure people when their health became poor. Just as the Decade was about to begin, prominent experts in health economics made the influential argument that primary health care (PHC), as envisioned by the WHO at the Alma Ata Conference, needed to be replaced with what they called selective primary health care. PHC was just too expensive; water was especially so. But oral rehydration therapy was not. Wasn’t simply curing children of diarrhea once they had gotten it a more cost-effective way to address the problem than supplying expensive water and sewer works? It was certainly more measurable. But when analyzing the IDWSSD’s impact on childhood diarrhea—often used as a marker for a community’s well-being as well as a sort of proxy for its access to clean water—the Decade’s Steering Committee for Cooperative Action reported in 1990 that claims that water supply and sanitation were too expensive, and that water supply and sanitation’s effect on health was too difficult to measure, were in fact wrong. By the end of the Decade, it was clear that providing water and sanitation had a demonstrable, quantifiable benefit in reducing childhood diarrhea.[iv] While there is no doubt that the Water Decade did not achieve all of its goals, the very fact of its ambition, to say nothing of its actual achievements, is remarkable. The Decade brought an extraordinary amount of attention to the poor state of water supply and sanitation in much of the world. And in urban Africa, the gains in access to drinking water made during the Water Decade, in which direct house connections increased from 29% to 49%, were greater than those made in the 25 years between 1990 and 2015, in which access actually dropped from 43% to 33%. This drop was despite UN’s Millennium Development Goals, which set access to clean drinking water as one of its pillars and had a target date of 2015.

The BNHP was an attempt to think about disease, the environment, economic development, and human behavior all at the same time. The irrigation projects in the Gezira region of Sudan had created an entirely new economic and environmental region within the country. Malaria and schistosomiasis were products, of course, of the natural environment, but that environment was formed by human action. Before the Sennar Dam was built in the early 1920s, schistosomiasis was barely known. But officials predicted right away that it would become a problem. In 1952, W. H. Greany from Sudan’s Ministry of Health noted that “this previously waterless area became invaded by schistosomiasis after the introduction of a system of irrigation.”[v] It was clear to the WHO by the end of the 1940s that schistosomiasis had spread across Africa in the wake of irrigation development. By the end of the 1950s, it was well known that irrigation projects across the world—in Brazil, Venezuela, Rhodesia, Egypt, and elsewhere—were breeding grounds for schistosomiasis. And malaria, once a seasonal malady, had been slowly turning into a year-round one in the 1970s.

What happened in Sudan was a version of a global phenomenon seen in many places that manifested in myriad ways: the total environmental transformation of a landscape after the introduction and rapid spread of capital-intensive agriculture geared toward commodity production. It might seem remarkable now—or perhaps it does not?—but it was a novel realization at the end of the 1970s that water, in this unique environment, linked malaria, diarrhea, and schistosomiasis and that rethinking water control might lead to better health outcomes. As a 1980 WHO press release trumpeted, “The multi-faceted plan is key to a new strategy of disease control that is being put into effect on a large scale for the first time. Designed to tackle all of the area’s health problems, it is comprehensive rather than piecemeal in scope, and represents a major shift away from a project-by-project approach.”[vi]

The architects of the BNHP took as their starting point the fact that the natural environment of the Gezira province had been fundamentally altered: a region that had barely known water-associated disease had been made into an environment where water-associated diseases were endemic and occasionally epidemic. The BNHP acknowledged that with the imperative of economic development came responsibility. The World Bank—a key partner in financing portions of the project through its simultaneously run Gezira Rehabilitation and Modernization Project—proposed that there was in fact a moral component to irrigation development. “[I]nterventions which are known to increase substantially the spread of serious disease cannot be undertaken lightly. If they are embarked upon lenders would seem to be morally obligated not only to institute effective counter measures to offset these dangers but to reduce the remarkable increase in waterborne diseases that for example the irrigation schemes in Sudan have produced.”[vii]

The architects of the BNHP took as their starting point the fact that the natural environment of the Gezira province had been fundamentally altered: a region that had barely known water-associated disease had been made into an environment where water-associated diseases were endemic and occasionally epidemic. The BNHP acknowledged that with the imperative of economic development came responsibility. The World Bank—a key partner in financing portions of the project through its simultaneously run Gezira Rehabilitation and Modernization Project—proposed that there was in fact a moral component to irrigation development. “[I]nterventions which are known to increase substantially the spread of serious disease cannot be undertaken lightly. If they are embarked upon lenders would seem to be morally obligated not only to institute effective counter measures to offset these dangers but to reduce the remarkable increase in waterborne diseases that for example the irrigation schemes in Sudan have produced.”[vii]

But would it be possible to determine whether the health component of a project would have a reasonable chance of success? As was asked about the Water Decade: Can health be measured? To try to answer these questions, the Bank sent Dr. Graham Clarkson to investigate. Clarkson determined that the BNHP’s goals were reasonable and its capacity sound. He offered a word of caution to the finance team at the Bank: don’t get too fixated on quantification. His thorough assessment of the program and its possibilities came to the not-unsurprising conclusion that quantifying the benefits of schistosomiasis control was neither possible nor necessary. That is, the harm the disease was doing to workers and others in Gezira was self-evident; improvement in health would lead to economic improvement.[viii] With the Bank’s concerns now allayed, it was prepared to offer funding.

The architects of the BNHP imagined that their project would be a model for other tropical countries faced with diseases their environment created when water resources were developed for food, energy, and commodity production. To that end, the Bank set aside $60 million to mitigate the effects of irrigation development on health. The BNHP was part of a broader set of research efforts, such as the Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases, that aimed to better understand common diseases across a broad swath of the planet. The Special Programme began, in fact, as a response to the “frightening increases in prevalence and severity” of malaria and schistosomiasis due to water development schemes.[ix]

Over the course of the 1970s, it was increasingly obvious that a comprehensive approach could be far more successful than a piecemeal one. Just as those who planned the Water Decade thought about water in an all-encompassing and ambitious way, so, too, did the designers of the BNHP. To achieve their goals, they initially set up a study area to learn what worked and what did not. They tried everything in tandem. Village health committees were formed; volunteers were trained in malaria and schistosomiasis diagnosis; and mothers learned how to use oral rehydration salts to combat diarrhea. The Bank funded the construction of community water supplies and more efficient drainage canals to reduce standing water. Centrally operated mass chemotherapy programs treated schistosomiasis. The Chinese Grass Carp was introduced to reduce aquatic weeds, mosquito larvae, and snails.[x]

Did the BNHP work? In many respects, yes—and in a remarkably short period of time. In 1985, Dr. A. A. El Gaddal, the BNHP’s project manager, reported that schistosomiasis had been reduced from a prevalence rate of more than 50% to less than 10%; malaria and diarrhea rates fell considerably as well.[xi] And success was sustained for the 10-year lifespan of the BNHP. Schistosomiasis was kept at bay throughout the 1980s. Malaria prevalence dropped below 1% from a high of over 30% in the early 1970s.[xii]

But it all came to an end. The coup that toppled the Sudanese regime in 1985 and installed Omar Bashir as president lead to political instability. Many on the staff were jailed; others fled. And the BNHP relied more and more on outside expertise. Still, year after year, as long as funding was available, success was the norm—until 1990. That year, torrential rain overwhelmed the drainage systems and malaria swept the Gezira. By then, too, and as planned, foreign financial support had come to an end, and the Sudanese government was unable to pick up the slack. While the BNHP had provided 10 years of good health, and the Bank had financed the construction of clean water and sanitation works, many of the gains were ephemeral. There had not been enough time to develop biological methods of snail control; the provision of free chemical biocides was too good to pass up. Bed nets for malaria control had not been widely adopted. Because they relied on infrastructural changes—new water pipes, latrines, and so forth—the gains made in providing clean water and sanitation would, theoretically, last longer. Once the BNHP shut down, schistosomiasis was no longer a priority—for anyone. Halfway through the first decade of the 21st century, prevalence rates on the Gezira had climbed to more than 70% in males and 60% in females. And malaria has gone from being under control to becoming, again, a regular feature of the year and, at regular intervals, becoming quite intense.

What seems obvious from these two examples is that only long-term investment and sustained ambitions will work. In 1995, when the Bank appraised BNHP, this was clear: “The results achieved so far confirm that the reduction in the prevalence of the disease is a direct consequence of the duration of the disease control program.”[xiii]

Christian McMillen is a History Professor at the University of Virginia and the Associate Dean for the Social Sciences. His research focuses on the history of health, disease, and pandemics.

This blog post is based on a longer article, “Water and the Death of Ambition in Global Health,” published in História, Ciências, Saúde-Manguinhos.[xiv]

[i] Drinking Water and Sanitation, 1981-1990: A Way to Health, A WHO Contribution to the International Drinking Water Supply and Sanitation Decade (Geneva: WHO, 1981): 7.

[ii] Report of the United Nations Water Conference, Mar del Plata, Argentina, March 14–25, 1977, E. CONF.70/29, (1977), 66.

[iii] Strategies for Extending and Improving Potable Water Supply and Excretal Disposal Services during the Decade of the 80’s, Possible Strategies for the International Drinking Water and Sanitation Decade, Provisional Agenda Item 20, CD26/DT/2, June 25, 1979, WHO, 1.

[iv] Steering Committee for Cooperative Action, Report on IDWSSD Impact on Diarrheal Disease (IDWSSD, 1990).

[v] W. H. Greany, “Schistosomiasis in the Gezira Irrigated Area of the Anglo-Egyption Sudan. I. Public Health and Field Aspects,” Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology 46, no. 3 (1952): 250–67, 265.

[vi] Peter Orozio, “$155 Million Programme in Blue Nile Area of Sudan Tackles Diseases Linked to Irrigation,” Donors Conference Set for Khartoum 24-26 February, Gezira Rehabilitation Project – Sudan – Credit 1388 – P002587 – Correspondence – Volume 2, October 1, 1980–January 28, 1982, Folder 811817, World Bank Archives.

[vii] Harold Messenger, Office Memorandum, “Assessment of Waterborne and Related Diseases in Relationship to the Gezira Rehabilitation and Modernization Project 1,” 14 December 1981, Gezira Rehabilitation Project – Sudan – Credit 1388 – P002587 – Correspondence – Volume 3, October 1, 1980–January 28, 1982, Folder 811818, World Bank Archives.

[viii] Sudan Gezira Rehabilitation Project, Schistosomiasis Component, Annex 3E of Sudan Gezira Rehabilitation Project, Implementation Volume, Volume I/Annexes I-IV, WBG Archives.

[ix] Memo from Warren Baum and Shirley Boskey to Robert McNamara, President of the World Bank, “Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases,” November 12, 1976, Background materials for Bank participation in tropical diseases research-set, R1992-049, Folder 1103166, World Bank Archives.

[x] The best discussion of the BNHP’s strategies is William Jobin, “Historical Analysis of Gezira-Managil Irrigation System on the Blue Nile,” in Dams and Disease: Ecological Design and Health Impacts of Large Dams, Canals and Irrigation Systems (London: E & FN Spon, 1999), 321–360.

[xi] A. A. el Gaddal, “The Blue Nile Health Project: A Comprehensive Approach to the Prevention and Control of Water-Associated Diseases in Irrigated Schemes of the Sudan,” Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 88, no. 2 (1985): 47–56. For the schistosomiasis rate. see Mutamad Amin and Hwiada Abubaker, “Control of Schistosomiasis in the Gezira Irrigation Scheme, Sudan,” Journal of Biosocial Science 49, no. 1 (2017): 83–98, 89.

[xii] Jobin, “Historical Analysis of Gezira-Managil Irrigation System on the Blue Nile,” 341–42.

[xiii] Implementation Completion Report, Sudan, Gezira Rehabilitation Project (Credit 1388-SU), March 2, 1995, Report No. 14024-SU, Agriculture and Environment Operations Division, Eastern Africa Department, Africa Region.

[xiv] Christian McMillen, “Water and the Death of Ambition in Global Health, c. 1970–1990,” História, Ciências, Saúde-Manguinhos 27 (September 2020).

[1] Drinking Water and Sanitation, 1981-1990: A Way to Health, A WHO Contribution to the International Drinking Water Supply and Sanitation Decade (Geneva: WHO, 1981): 7.

[1] Report of the United Nations Water Conference, Mar del Plata, Argentina, March 14–25, 1977, E. CONF.70/29, (1977), 66.

[1] Strategies for Extending and Improving Potable Water Supply and Excretal Disposal Services during the Decade of the 80’s, Possible Strategies for the International Drinking Water and Sanitation Decade, Provisional Agenda Item 20, CD26/DT/2, June 25, 1979, WHO, 1.

[1] Steering Committee for Cooperative Action, Report on IDWSSD Impact on Diarrheal Disease (IDWSSD, 1990).

[1] W. H. Greany, “Schistosomiasis in the Gezira Irrigated Area of the Anglo-Egyption Sudan. I. Public Health and Field Aspects,” Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology 46, no. 3 (1952): 250–67, 265.

[1] Peter Orozio, “$155 Million Programme in Blue Nile Area of Sudan Tackles Diseases Linked to Irrigation,” Donors Conference Set for Khartoum 24-26 February, Gezira Rehabilitation Project – Sudan – Credit 1388 – P002587 – Correspondence – Volume 2, October 1, 1980–January 28, 1982, Folder 811817, World Bank Archives.

[1] Harold Messenger, Office Memorandum, “Assessment of Waterborne and Related Diseases in Relationship to the Gezira Rehabilitation and Modernization Project 1,” 14 December 1981, Gezira Rehabilitation Project – Sudan – Credit 1388 – P002587 – Correspondence – Volume 3, October 1, 1980–January 28, 1982, Folder 811818, World Bank Archives.

[1] Sudan Gezira Rehabilitation Project, Schistosomiasis Component, Annex 3E of Sudan Gezira Rehabilitation Project, Implementation Volume, Volume I/Annexes I-IV, WBG Archives.

[1] Memo from Warren Baum and Shirley Boskey to Robert McNamara, President of the World Bank, “Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases,” November 12, 1976, Background materials for Bank participation in tropical diseases research-set, R1992-049, Folder 1103166, World Bank Archives.

[1] The best discussion of the BNHP’s strategies is William Jobin, “Historical Analysis of Gezira-Managil Irrigation System on the Blue Nile,” in Dams and Disease: Ecological Design and Health Impacts of Large Dams, Canals and Irrigation Systems (London: E & FN Spon, 1999), 321–360.

[1] A. A. el Gaddal, “The Blue Nile Health Project: A Comprehensive Approach to the Prevention and Control of Water-Associated Diseases in Irrigated Schemes of the Sudan,” Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 88, no. 2 (1985): 47–56. For the schistosomiasis rate. see Mutamad Amin and Hwiada Abubaker, “Control of Schistosomiasis in the Gezira Irrigation Scheme, Sudan,” Journal of Biosocial Science 49, no. 1 (2017): 83–98, 89.

[1] Jobin, “Historical Analysis of Gezira-Managil Irrigation System on the Blue Nile,” 341–42.

[1] Implementation Completion Report, Sudan, Gezira Rehabilitation Project (Credit 1388-SU), March 2, 1995, Report No. 14024-SU, Agriculture and Environment Operations Division, Eastern Africa Department, Africa Region.

[1] Christian McMillen, “Water and the Death of Ambition in Global Health, c. 1970–1990,” História, Ciências, Saúde-Manguinhos 27 (September 2020).