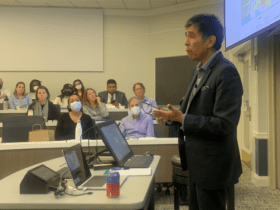

To celebrate World Water Day, David Keiser gave a talk at the Batten Policy School at the University of Virginia. David Keiser is a prolific assistant professor at Iowa State University who has been writing about water quality. He is perhaps best known for his study with Joe Shapiro (Berkeley) that assesses the impact of the Clean Water Act, and their follow-up literature review in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that underscores how most of the Cost Benefit analyses of the Clean Water Act reveal costs surpassing (measured) benefits. David Keiser spoke to us about the Economic impact of the Flint water crisis a few years back. We asked him a few questions.

Can you remind us again what happened in Flint, Michigan?

Sure. Thanks for the invitation to Virginia.

Back in the spring of 2014, the city of the Flint decided to switch its drinking water supply from Detroit to the Flint River. This was intended as a temporary way to save the city money while it waited to connect to a cheaper water supply that was being developed.

Shortly after this switch, Flint residents began to complain about the quality of their drinking water. It smelled bad, tasted bad, and was discolored. Over the course of the next year and a half, residents complained bitterly about the water, but were told by local officials that it was safe to drink. It was only after an independent testing campaign by researchers at Virginia Tech and efforts by local residents and a local pediatrician that it was discovered the city had a major problem on its hands. After switching to the Flint River, local drinking water personnel failed to implement a proper corrosion control program. This failure caused lead to leach in to the water supply from lead service lines. These lines (i.e., pipes) connect individual homes to the city’s water distribution network. A public health emergency was declared in October of 2015, followed by a Federal emergency declaration in January 2016. These emergency declarations led to a massive effort to understand the lead issue within the city and figure out a way to correct it. The city still hasn’t replaced all of the problematic service lines, but has declared the water safe to drink again. As you might imagine, many residents are still skeptical.

Why did you think it was important to revisit the Flint events from an economic perspective?

We actually started our project many years ago (before the emergency declarations). One of my co-authors on the project, Gabe Lade, noticed a New York Times article in March of 2015 detailing the complaints of residents before it was clear there was a major issue on hand. We began the project with an interest in understanding how conflicting information signals (households experiencing dirty water vs. being told it was safe) influenced decisions to engage in averting behavior, or steps to reduce potential exposure to pollution (e.g., buying bottled water, filters, etc.). Once the crisis unfolded, we expanded our study to look at how the switch and subsequent crisis also influenced the housing market in Flint. We think it’s important to understand the economic impacts of a crisis such as Flint in order to design better policies to prevent them from happening in the first place.

You bring an interesting perspective to the study by looking at the value of the housing stock and how it is affected by the crisis. You also bring in scanner data from super markets in the area that allowed you to track the sale of water bottles in the Flint area. Why were you interested in those two aspects of the crisis?

Initially we were interested in bottled water since these purchases reflected the extent that households were engaging in averting behaviors and the resulting economic impacts of the switch to the Flint River. We were interested in both the magnitude and duration of these behaviors.

Once the crisis was revealed, we extended our analysis to home values as well since these could reflect the larger impacts of the crisis. For example, housing values in Flint after the crisis reflect not only the increased costs associated with having to deal with unsafe water, but also the impacts of the crisis on trust in local officials and the broader desirability to live in a city that is facing a crisis. Economists have used both types of market transactions to infer society’s willingness to pay to avert these types of events from occurring. These methods have a long history in measuring the benefits of controlling air and water pollution. The methods are often cited in major federal regulations such as the Clean Air Act and Safe Drinking Water Act.

So what did you find, and what surprised you?

So far we have found a large and sustained increase in the sales of bottled water after the switch to the Flint River. Not surprisingly, these sales collapsed once bottled water was available for free after the crisis. These results suggest that Flint residents mistrusted that the water was safe and were willing to pay a significant sum of money to drink water that tasted and looked better. This finding is pretty interesting in its own right since it suggests there was a significant cost to the switch even in the absence of the crisis. In fact, we find that Flint residents paid as much money to purchase bottled water after the switch as what the city expected to save from the switch to the Flint River. These results are also informative for other studies that have examined the human health impacts of the crisis. What our results suggest is that the increase in purchases of bottled water helped mitigate a larger health crisis.

As far as the housing market goes, we find that the prices of homes decreased after the switch to the Flint River and then experienced a much steeper decrease after the crisis was revealed. The large magnitude of these effects suggest that the crisis placed a significant toll on the value of the housing stock in Flint. Somewhat surprisingly, we don’t find that these effects were correlated with increased (individualized) lead risk within the city. It appears the whole city was shocked systemically by the crisis. Currently, our study period goes through the middle of 2017, so it will be interesting to see to how long these impacts persist.

It’s been heartbreaking to follow the personal stories of the crisis in the news. We hope these findings help shed light on the impacts of this particular crisis and serve as useful information to inform better policies going forward.